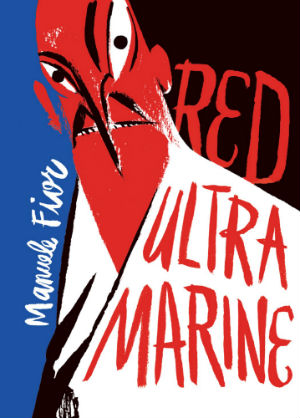

One of the greatest strengths of comics is that in being a purely visual medium, they can use evocative cartooning to charge even the most threadbare of plots with meaning. This is certainly true of the dreamlike narrative of Manuele Fior’s Red Ultramarine. Leaning heavily on symbolic imagery drawn from the Greek myths of Icarus and the Minotaur as well as the German story of Faust, Fior crafts a visually striking meditation on the dangers of obsession and the redemptive power of love. While the themes Fior is engaging with have been explored countless times before, it is his strong expressive cartooning and his daring use of color that make his interpretation of the material he is drawing from stand out.

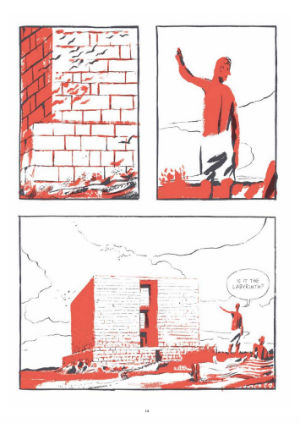

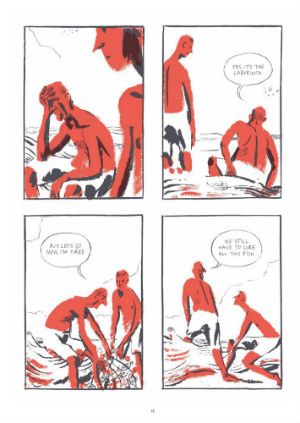

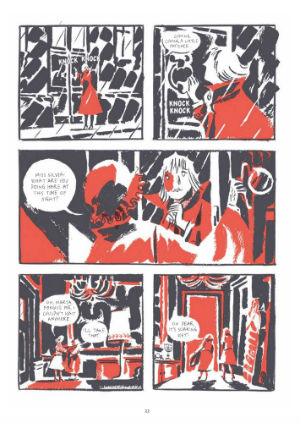

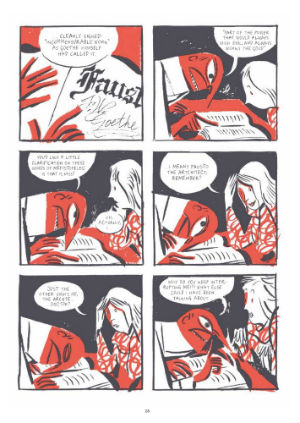

Looking as if it were scratched out of the page in black and red, Fior’s line work is distinctly European but unique in its rough disintegrating brush strokes. His blacks are speckled and broken, at times spilling over word balloons and panel borders. His reds show even less allegiance to the shapes they are contouring as they overlap and overrun both white and black areas within the panel. Rather than use red as a slight accent for occasional effect, Fior covers the page with it. Icarus and Daedalus’ sun-drenched bodies are coated in red, but then so are the waves that crash against the shores of Crete. Later this same red is used more archetypally to capture the rage and brutality of the Minotaur, or the diabolical presence of the Mephistophelian doctor. And in a final bit of visual storytelling, it is only when protagonist Sylvia and her love interest Fausto are able to remove the red from their faces that both find the peace they have been seeking.

Looking as if it were scratched out of the page in black and red, Fior’s line work is distinctly European but unique in its rough disintegrating brush strokes. His blacks are speckled and broken, at times spilling over word balloons and panel borders. His reds show even less allegiance to the shapes they are contouring as they overlap and overrun both white and black areas within the panel. Rather than use red as a slight accent for occasional effect, Fior covers the page with it. Icarus and Daedalus’ sun-drenched bodies are coated in red, but then so are the waves that crash against the shores of Crete. Later this same red is used more archetypally to capture the rage and brutality of the Minotaur, or the diabolical presence of the Mephistophelian doctor. And in a final bit of visual storytelling, it is only when protagonist Sylvia and her love interest Fausto are able to remove the red from their faces that both find the peace they have been seeking.

With this striking aesthetic Fior intercuts between a narrative exploring the father and son relationship of Daedalus and Icarus and the modern day story of Sylvia’s quest to cure her boyfriend Fausto of his architectural obsession. The book begins with Daedalus and Icarus on the beach in Crete, the latter content with their simple fisherman life and the former eager to get off the island and away from the labyrinth he has made. Meanwhile in the present, after Fausto shuts himself inside the house with his architecture work, a desperate Sylvia goes out into the stormy night to seek answers from the Mephistophelian doctor. Just as Daedalus will come to be trapped in a labyrinth of his own making, so too is Fausto trapped by his obsession with what the doctor calls circling the square and discerning the truth of the world. The parallel is highlighted by the visual echo of the labyrinth in Fausto’s drawings. While doctor chides Sylvia for being so invested in a man who’s sunk in his desire to kill the metaphorical Minotaur, his maid however offers her comfort and a mysterious balm to cure her of the red birthmark on her face.

This mirroring of the characters is nicely extended to the book’s visual storytelling. The observant reader notices the serpent and Minotaur statue in the doctor’s office that visually echo their corollaries in Crete. A strong use of this technique is seen in the way both Daedalus and Fausto stare out at the red waves, the former weighing the result of his creation, the latter the weight of his inability to reach such heights. For though Fausto is himself a direct nod to the story of Faust, his deal with Mephistopheles is never specified. Much clearer is Daedalus’ deal with devilish King Minos where the creation of the labyrinth to house the bestial Minotaur is at first his salvation and later the prison that will destroy him.

After Daedalus and his son are condemned to the labyrinth for the death of the Minotaur at Theseus’ hands, Fior intermingles both the Grecian and Faustian worlds to further emphasis their parallels. In what seems at first to be a dream brought on by the skin cream given to her by Marta, Sylvia will walk through a door and ends up on the beach in Crete. There while gazing at Icarus she will confuse him with Fausto, subtly connecting both as men who are trying to fly to close to the sun and the dangers therein. A comparison further echoed by Fausto’s near fall out a window in depths of a work related hallucination, saved only at the last second by Sylvia pulling him back from the brink. The reader will enter the book already knowing the fate of Icarus, making the only character to truly escape from the labyrinth the never seen Theseus aided by the love of Ariadne. Though perhaps if Fausto can see the depths to which Sylvia loves him, then that will be the thread that leads back to freedom.

By treading so heavily in signs and symbols Red Ultramarine is a book that sticks with the reader. Not for any particular line of dialogue or twist of the plot, but in flashes of individual panels that pulse with heart and magic. Archetypes and allusions as they might be, Fior gives both his protagonists and his antagonists such vitality through his cartooning that the reader cannot help but invest in them. As lightly sketched as Sylvia and Fausto’s relationship is, Fior’s ability to capture their emotions world compels the reader to hope that they can avoid the tragedy that awaits Icarus and Daedalus. For the only way to escape the monster at the heart of the labyrinth of obsession is to give up the search for the things beyond our reach and to accept the love that surrounds us. It’s right there on the page, in black, and white, and red.

Manuele Fior (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books, $19.99

Review by Robin Enrico