When Karen Berger’s party train pulled out of UK Comics Central in the late 1980s, one passenger was left unexpectedly on the platform: writer John Smith, whose penchant for loopy high concepts, visceral horror and fragmented postmodern storytelling looked certain to usher him to a forward-facing seat in first class. However, a mutual wariness restricted his output for DC to eight issues of Scarab (a mutated reworking of Dr Fate) and a much-feted single issue of Hellblazer (#51).

Anyway, DC’s loss was very much 2000 AD’s gain, as Script Droid Smith threw his considerable imaginative energy into creating a string of series for the Galaxy’s Greatest Comic (along with the connected Judge Dredd: Megazine). And perhaps the most quintessential of his stories was Revere – a hallucinatory collaboration with artist Simon Harrison that ran sporadically in 2000 AD between 1991 and 1994. Having only ever been reprinted in the form of a 2000 AD Extreme Edition back in 2007, it has acquired a fittingly mythical reputation.

Anyway, DC’s loss was very much 2000 AD’s gain, as Script Droid Smith threw his considerable imaginative energy into creating a string of series for the Galaxy’s Greatest Comic (along with the connected Judge Dredd: Megazine). And perhaps the most quintessential of his stories was Revere – a hallucinatory collaboration with artist Simon Harrison that ran sporadically in 2000 AD between 1991 and 1994. Having only ever been reprinted in the form of a 2000 AD Extreme Edition back in 2007, it has acquired a fittingly mythical reputation.

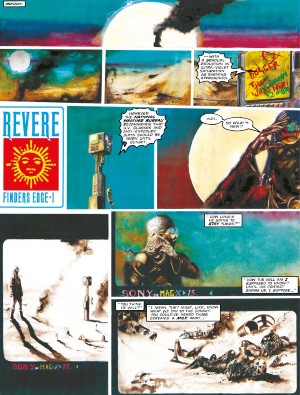

Reflecting the technopagan vibe that was thick in the air at the time, Revere is the near-future story of ‘the witchboy of London town’. With prescient environmental awareness, Smith and Harrison show us a future maimed by climate catastrophe – a parched, desertified Britain in which precious water resources are controlled by a shadowy crypto-fascist cabal, led by ‘The Baron’ and acting through their paramilitary enforcers (‘Lanzers’).

The plot of Revere soon becomes a little slippery. However, the first of the three ‘books’ (each comprising just six six-page episodes) forms a satisfying and intriguing overture. After a day making ends meet in the brutal shadow economy, Revere’s astral projection is hijacked by a mysterious ‘Hermit’ who addresses him as ‘the Aquarian’ and informs him blithely that he is destined to save the world by destroying it.

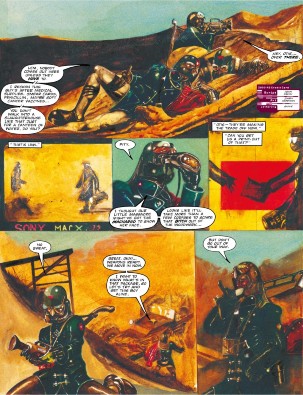

However, Smith characteristically embellishes this narrative spine with a kaleidoscopic dazzle of ideas. As various new age concepts are tossed into the mix, it’s how The Usual Suspects might have turned out had ‘Verbal’ Kint been stuck in a Glastonbury tat shop rather than a detective’s office: the tarot, astrology, chaos magic, spiritual death and rebirth, sacred geometry, the dreamtime, chakras, cosmic whales and the embodiment of psychosexual kinks all put in an appearance. (Speaking of psychosexual kinks, there’s also what I imagine is 2000 AD’s most impressively delineated vagina dentata. I’m sure a Squaxx dek Thargo out there will put me right if that’s not the case.)

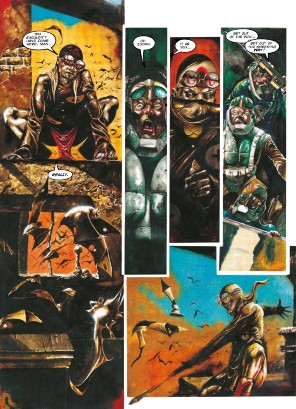

Book Two provides a bit of a training montage and makes things personal, as the witchboy’s lover is abducted by his subconscious manifestations and the Motherhead is captured by the Lanzers. Book Three then sees Smith step sideways into Moorcockian quest mode, as Revere crosses the dimensions in search of Chloe. At its conclusion, we spin back to the Hermit’s prophecy and see Revere bring about the great transformation we were promised earlier.

Some of the story’s difficulties may be explained by the fact that Smith’s wrote its conclusion while recovering from a particularly bad acid trip. Quoted in Thrill Power Overload (the official history of 2000 AD, he says, “That left me fucked up for weeks… Those last few episodes were me trying to write my way back to sanity. That’s probably one of the reasons the end is just so odd. I really was borderline psychotic when I wrote that. I haven’t taken LSD since.”

However, Revere also showcases why Smith’s writing makes such an impression on people. His imagery crackles with energy and imagination, creating a vivid picture of the character’s inner space that works in conjunction (sometimes harmoniously, sometimes in juxtaposition) with what we’re looking at. His allusions also hint at a huge and mysterious universe lurking beyond the edges of the page.

At least some of Revere’s reputation for obscurity can also be laid at the door of Simon Harrison, whose images were the starting point for the series. His fully painted artwork can be nothing less than astonishing when it’s hitting the chaotic heights and looking to express the Lovecraftian ‘unknowable’. However, it’s on less sure ground when dealing with regular human anatomy or creating a distinctive and consistent likeness for characters. The beady little ‘rabbit eyes’ he gives his characters is just one off-putting visual tick.

Smith’s many devoted acolytes will be thrilled that this core work of his is now back in circulation (with the slightly less seminal Slaughter Bowl and Firekind to follow later in the year), although I’m sure the digital-only nature of the release will ruffle a few feathers; despite its flaws, this is work that deserves to be experienced at full size. Still, Rebellion are to be applauded for making more of 2000 AD’s formidable archive accessible.

John Smith (W), Simon Harrison (A), Annie Parkhouse, Jack Potter (L) • Rebellion (digital only), £7.99

Review by Tom Murphy