Reverse Flâneur by M. Sabine Rear is a travelogue in multiple senses of the word. On one hand it serves as vicarious document of Rear’s time visiting art museums in Vienna with her family. On the other it is an entree into Rear’s life as an appreciator of arts and culture who also happens to be blind. More a memoir than a biography of her experience as a disabled person, the comic is a snapshot of a particular time and a particular place that also contends with the lens framing that shot. By foregrounding her experience as a traveller and art connoisseur and discussing her disability in relationship to those experiences, Rear allow space for the reader to feel comfortable enough in those places where their own experiences align for them to begin exploring the places where they do not.

Reverse Flâneur by M. Sabine Rear is a travelogue in multiple senses of the word. On one hand it serves as vicarious document of Rear’s time visiting art museums in Vienna with her family. On the other it is an entree into Rear’s life as an appreciator of arts and culture who also happens to be blind. More a memoir than a biography of her experience as a disabled person, the comic is a snapshot of a particular time and a particular place that also contends with the lens framing that shot. By foregrounding her experience as a traveller and art connoisseur and discussing her disability in relationship to those experiences, Rear allow space for the reader to feel comfortable enough in those places where their own experiences align for them to begin exploring the places where they do not.

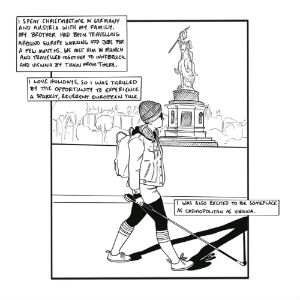

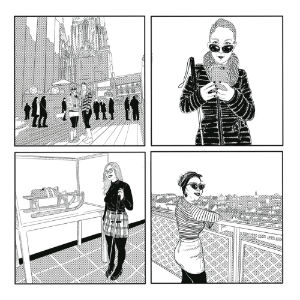

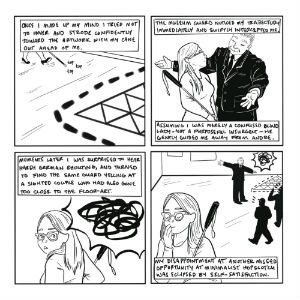

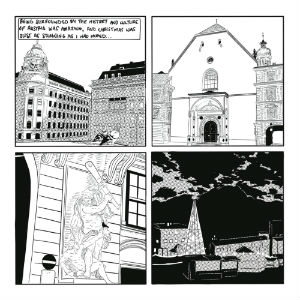

In a move that sets the tone for the book, Rear opens with narration explaining her family’s holiday season trip to Vienna over an image of her walking cane in hand past the equestrian statue of Archduke Karl in Hero’s Square. In not prefacing or over-explaining her blindness, Rear presents it as a given, allowing the reader to inductively pick up the parameters of her disability as the book progresses. The first vignette begins this process by exploring the clothing choices Rear makes for her trip by posing subtle queries of it own. As a blind woman Rear has to contend not only with the practical concerns of her travel garments but the aesthetic ones as well. Taking a page from Dita Von Teese, Rear decides to dress glamorously while traveling, both as a form of self-actualization and as means to challenge ableist notions surrounding her abilities. With her mix of nicely detailed renderings of clothes and locations mixed with her lightly cartoon-y, though properly proportioned, people Rear gives the reader a splash page of hip outfits and a series of detailed self-portraits drawn from her own selfies. Making it clear that despite her visual impairment Rear is more than capable of presenting herself as a fashionable young woman. The reader must then questions not just their own prejudices towards the blind but also their own perhaps schlubby travel wardrobe.

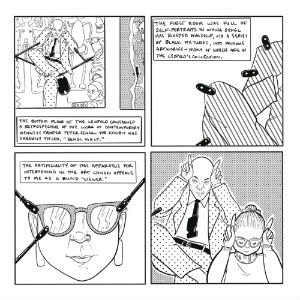

While she takes extra effort to control her image, Rear is still very conscious of the way in which her disability impacts the way others perceive her. Visiting an Egon Schiele exhibit at the Leopold Museum she is acutely aware of gaze of sighted people upon her. She sets up a strong parallel here in that amidst the harshly bent and amputated figures of Schiele’s work, it is Rear’s body that is viewed as broken. Moved as she is Schiele’s work, she has an even deeper connection with an exhibit of work by the Viennese painter Peter Sengl where he had affixed his self-portrait to reproductions of famous artwork; Sengl’s use of artificial apparatus to make himself part of works of art paralleling Rear’s need for glasses to partake in the work. When Rear recreates Sengl’s grotesque paintings of machinery grafted onto amputated bodies the reader connects these images back both to Schiele’s work and Rear’s reliance on the machinery of her cane and glasses, further probing the question of how we view the less than perfect body.

This idea of how the imperfect body is both lived in and perceived is central to Rear’s concerns here. In a daring move, she presents the reader with quotations from Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto and Rosemarie Garland-Thompson’s The Politics of Staring to further push the reader into examining how they perceive Rear’s mechanically assisted body in contrast to her experience within it. Haraway advocating that a cyborg world would be opened up to new possibilities by not being, “afraid of permanently partial identities” like those of the disabled. Or as Garland-Thompson argues, staring at the disabled body makes the “viewers furtive and the viewed defensive”, narrow-mindedly othering the subject of that gaze instead of seeing it as another variation on the human from. This is heady stuff but Rear succeeds in leading the reader to this point through the words and visual metaphors in the museum. Even in opening our minds and being receptive to Rear and her othered body we have to contend with how ingrained this othering is in our culture. When in the gift shop she notices a banner reading, “all art is erotic” the reader may consider the transgressive potential of art and set it against the transgressive status of the disabled body. It speaks highly of her abilities and confidence as a visual storyteller that she knows the reader will connect the dots on these more complex points and have them land all the stronger for it.

This theme of the transgressive body continues into later pages where Rear renders a trio of horse-headed buskers and the forms of the bird-headed women from a mural in a Viennese café. These figures draw her to the space and make her time in the café feel both glamorous and comfortable. As a disabled woman there is something powerful about her existing alone in public space, particularly in contrast to her experience at the museum. In the café the act of knitting a scarf allows Rear to reclaim her identity by making her approachable and invisible, setting people at ease instead of having them react voyeuristically to her disability. She cannot be so innocuous when walking with her cane and prefers to imagine it as the type of sexy legs that precede a woman getting out of a car in a sleazy cartoon, transforming the pitiable appendage into an object of desire. In a similar transformation, while Rear’s family goes off hiking she is able to experience her own version of the romance of travel by drawing in the café while listening to records and indulging in fancy deserts and liqueurs. The transgressive body is then a fabrication of the viewer unable to see neither the potential therein or the way said body fits into the world just as well as the able one.

In the final sequence, Rear plays with others perceptions of her blindness. Using her disability to cloak her insurgency, she tries to step on a Carl Andre piece displayed on the floor of the Pinakothek der Moderne in protest of death of Ana Mendieta. Rear is stopped gently by the museum guard who sees her only as a confused blind woman, later yelling at a sighted couple who had accidentally wandered too close to the piece. Lastly she takes in Stephen Pina’s Monochrome Painting installation at the Mumok, where each painting is sized to mirror another monochromatic work in the art cannon. In the center of these featureless objects, Rear can have a rare moment of viewing the paintings at the same level of fidelity as a sighted person. The idea is transmitted to her in full clarity even without “seeing” it and amidst all her other powerful art experiences in Vienna this becomes the most moving.

In creating a fully realized travelogue from the perspective of a blind woman Rear causes the reader question their experience abroad. Is travelling about taking in as much as the eye can absorb, or instead training whatever vision we might have the most resonance to us? That Rear’s final image is of the New Year’s pig paraphernalia tells us far more about her eye than it does about Vienna’s culture. What are eyes when we can take a picture and forever capture a moment in better clarity that our memory might be able to? Is the photo is as much a curated moment as the memory as seen through Rear’s awareness of how she presents herself in her selfies? What is certain from Reverse Flâneur is that any prejudices the reader might have about Rear’s ability to travel, appreciate art, or be a cartoonist as a blind woman are no more than that. That she can address these complex ideas with such confidence in this slim volume is staggering. This is the work of an artist functioning at a high level on all conceptual and aesthetic cylinders, moving the mind as much as the heart.

M. Sabine Rear (W/A) • Self-Published $10.00

Review by Robin Enrico

[…] queering space, cripping fashion and the museum, and challenging visuality thru comics. Review on Broken Frontier. As Vicki pointed out when we met in November 2018, I would need to think about the power […]