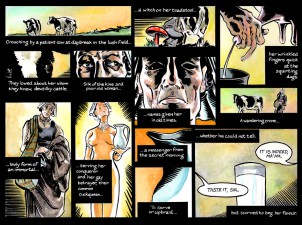

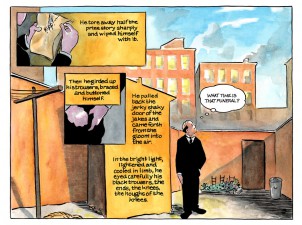

In the first part of our interview, published yesterday to coincide with Bloomsday, Rob Berry, the artist behind the Ulysses “Seen” graphic novel adaptation of James Joyce’s colossal novel, told us about his background and method in turning some of the most iconic prose in literature into comic pages.

Today, he tells us about how the literary establishment has responded to his work, the controversy over nudity in it and which classic comics James Joyce was a fan of.

Given the antipathy shown to comics by sections of the literary establishment, it must have been great when the James Joyce Centre got involved. How did that come about? And what sort of reaction have you had from Joyceans more generally?

I think I’d probably disagree with you about any antipathy shown to comics. It’s a very swiftly changing environment out there now, and quite a lot of important literary folk, with all the right academic pedigree, are becoming very interested in the art form.

I think I’d probably disagree with you about any antipathy shown to comics. It’s a very swiftly changing environment out there now, and quite a lot of important literary folk, with all the right academic pedigree, are becoming very interested in the art form.

Yes, these are younger PhDs, a generation who grew up in the acceptance of Maus and Black Hole rather than having to justify their adolescent reverence for Jack Kirby, but it’s making fora really different world academically.

I’ve heard many people compare it to the growth of “film studies” at colleges during the 1970s; there is a serious interest there to explore the significant work of an art form that stands somewhere between pop culture and auteur vision.

But it’s difficult because so much of the deeper history of comics is so production-based and fad-determined. In moving from painting to comics, I knew I was doing it pretty late in life and wanted to make something interesting for what I saw as a new developing educational market. But very few young cartoonists get the chance to make that kind of conscious choice.

The Joyce Centre had been following the project since it began. Changes in the international public domain status of the novel in 2012 meant that we could now put the project in front of a lot more Joyce fans by posting it on their website. We started that last year while developing some new features for our app, and the response has been fantastic. There’s clearly an interest, an international interest at that, in our approach to making Joyce accessible for new readers.

The Joyce Centre had been following the project since it began. Changes in the international public domain status of the novel in 2012 meant that we could now put the project in front of a lot more Joyce fans by posting it on their website. We started that last year while developing some new features for our app, and the response has been fantastic. There’s clearly an interest, an international interest at that, in our approach to making Joyce accessible for new readers.

Not everyone wants Joyce to be more accessible of course, and some people would argue that Ulysses is meant to difficult. But we’ve found that to be a rather small group of curmudgeons, compared with the thousands of new fans we’ve met through the encouragement of teachers, librarians and enthusiasts all over the world. It’s not an easy book, and Joyceans all seem to agree that we’re really just doing our best to help people enjoy it.

The Apple controversy must have been very stressful, but in hindsight was it helpful to become a cause celebre? (Apple requested the creators of Ulysses “Seen” to remove some images of nudity from the adaptation before allowing it into their app store.)

Stressful indeed. Remember, we’d tailored the entire model as a new kind of annotated comic for use on the iPad, pretty far in advance of that device’s release. To hear them say that the app itself was fine but that the use of nudity was being restricted felt, well, kind of ridiculous. After all, the book won what is probably the most famous case about obscenity restrictions in American law more than 80 years earlier.

But the outpouring of support we received was fantastic. Our app was still free in those days, so the people interested in it by the debate were able to download it easily and see for themselves what it was we were trying to do. This brought new readers to Joyce, new encouragement for our project and new projects with other great adaptations, like Martin Rowson’s The Waste Land and Eric Shanower’s Age of Bronze.

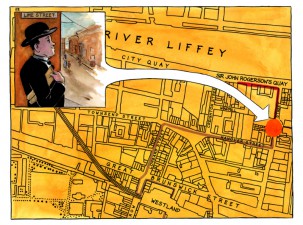

I read that you hadn’t visited Dublin prior to starting the adaptation. Did you have trouble visualising the city before you’d been, and did your conception of it change once you’d visited?

True. All my early work comes from lots of books and Google images. But even in the earliest days of the project people were happily sending me any reference material I’d ask for on our website.

True. All my early work comes from lots of books and Google images. But even in the earliest days of the project people were happily sending me any reference material I’d ask for on our website.

The thing wouldn’t have been possible without that kind of friendly Joycean community. Now that I’ve been there and met many of those people face-to-face I can get an amazing amount of reference shots for almost anything I need.

But nothing really prepares you for the small-town community feel of Dublin like being there. I knew it previously through maps and photos, but now, like Joyce himself, I’m starting to get a real sense of where things are in relation to others, how far a walk is and who or what I might see on the way. There’s no replacing that.

Dublin is as important a character in this novel as Bloom himself, and now every Bloomsday I get a chance to see what that looks like.

What’s the atmosphere like in Dublin during Bloomsday? (Each year on June 16th, special events are held in the city to commemorate Ulysses, including readings and dramatisations of episodes at their location in the book. There’s even cosplay!)

This book, and most of Joyce’s work, was kept apart from Dublin culture for years through the Joyce estate’s fairly unfriendly view of the culture the artist left behind. And many of his opinions about the culture and attitudes of the city certainly met with repression and condemnation from its citizens during the years that it was written. But, to my mind that’s an old argument between exiles and the home they speak of longingly. Joyce once wrote that he never left Dublin and that when he died the city would “be found engraved upon my heart.”

Now that the book has reached the public domain we’ve seen Irishmen all over the world trying to come to grips with it book means to their own sense of heritage. We’ve seen Dubliners embrace it as a portrait, a fairly too-frank look at “well, this is where you came from” that allows them to reach towards a modern identity for themselves that escapes the mirror Joyce held up in 1922.

But they’re proud – very proud – of fostering a famous son (whom was seldom understood in his own time) who wrote something that is unquestionably one of the greatest works of their accepted – if not chosen nor native – language. Bloomsday has become Dublin’s pride fest, as it ought to.

Bloomsday, after all, is the only worldwide literary holiday that I’m aware of. A celebration of one fictional moment that everyone understands as a triumph of literature, even if they’ve not yet dared to read it. And that happens every year across the globe. People turn their eyes to Dublin because of this great voice of one expatriate writer. I can’t think of a holiday to match that.

Are there any episodes of the book you’re particularly itching to get to – or dreading?

Yes to both. Itching to get to:

- ‘Lestrygonians’, with its mad, Bosch-like visions of food.

- ‘Wandering Rocks’, the selection of jump-cut stories that I hope to do with ten other guest cartoonists.

- ‘Circe’, the climactic brothel section that is so much like a play trying to stage a hallucination.

- ‘Penelope’, the famous concluding monologue by Molly Bloom that is so filled with sensuality that it’ll mean reimagining the format.

And dreading? Ahh…

- ‘Sirens’, a musical chapter. Music in comics? That’s difficult.

- ‘Cyclops’, one of my favorite chapters, but loaded with lists and names and really, really long.

Are there any cartoonists working today who Joyce might have felt an affinity with?

Joyce loved Krazy Kat and The Katzenjammer Kidz (or whatever name it had when he was reading it in Paris). I’ve already mentioned Chris Ware, but, obviously, David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp is like a love song to Joycean circumstance.

So, have you started planning your version of Finnegan’s Wake, then?

Nope. Never. I’ve a good friend, Clinton Cahill, who’s been mining the artistic possibilities of the Wake for years. But it’s brilliant stuff that can’t, to my mind, be adapted. Clinton’s work references and illuminates Joyce but never explains it. That’s for the best with something as enigmatic as the Wake.

‘Stick and Stone’, two artist’s books created by Clinton Cahill as part of his Illuminating the Wake project

But Ulysses can be adapted into comics and, with all the new features comics can give us on a digital page, the whole method for teaching this book to a new generation of readers can be significantly changed.

It’s not like making the old Classics Illustrations adaptations. We get a chance to rethink the form with every chapter and, to me, that feels particularly Joycey.

Once again, many thanks to Rob for taking the time to answer our questions.

Ulysses “Seen” is available as an app for the iPad (currently containing the first two episodes of the book), while the pages also appear on the website of the James Joyce Centre in Dublin; there you can find the ongoing third chapter of the work, a conflation of the ‘Lotus Eaters’ and ‘Nestor’ episodes.

In addition to his work on Ulysses, Rob has also illustrated a very special centenary edition of The Dead, the concluding short story in Joyce’s anthology Dubliners, published by Dublin’s Stoney Road Press. While the hand-printed book, in a limited edition of 150, comes in at €1,320, there’s also a Kindle edition for the rest of us!