You have to put up with a lot as a football fan. In that sense, they actually have a surprising amount in common with their natural nemesis: the comic book geek. Both have to take the rough with the smooth in order to enjoy their chosen/foisted passion. There comes the tacit understanding that your entertainment comes at the expense of unseen exploitation and the further lining of pockets already heavy with ill-gotten gains. There’s no ethical consumption under capitalism, as the 21st century bromide goes, whispered under our breath as we cross a turnstile or read of a work-for-hire royalties dispute or spend five seconds looking into PSG’s existence as a Qatari vassal state.

William Goldsmith and Christopher Rainbow’s fantastic Russia 2018: A Word Cup Journal does an admirable job of threading this familiar needle. They lead us on a picaresque, beautifully risographed tour around the host country each of the British cartoonists has called home (at least for a time). They acknowledge the obvious corruption of FIFA, whose award of the 2018 tournament to Russia was no doubt as financially-driven as the current Qatar World Cup. As the book seeks to explore the sport beyond the sins of its governing bodies and billionaire benefactors, it also depicts a country beyond “the limited range of stories considered newsworthy in the United Kingdom: Kremlin politics, civil rights oppressions, corruption and oligarchs; all valid and influential…but an incomplete picture.”

Each page of their World Cup Journal consists of a single entry that expands that picture considerably. Goldsmith and Rainbow show us all the other parts of football, beyond the headlines, rendered uncannily alien in a foreign context: a disappointing Panini sticker pack, its contents scattered in the streets of Moscow; a five-a-side game where the ball must be retrieved from waist-deep snow when it’s knocked out of play; hearts broken by games lost, watched on tablets and smartphones while stuck on cross-country train journeys. The pair watch games within the walls of the competition stadiums, in pubs and bars, in officially-designated outdoor “fan zones” and, in one memorable sequence, a TV set atop a box on a nudist beach in Sochi.

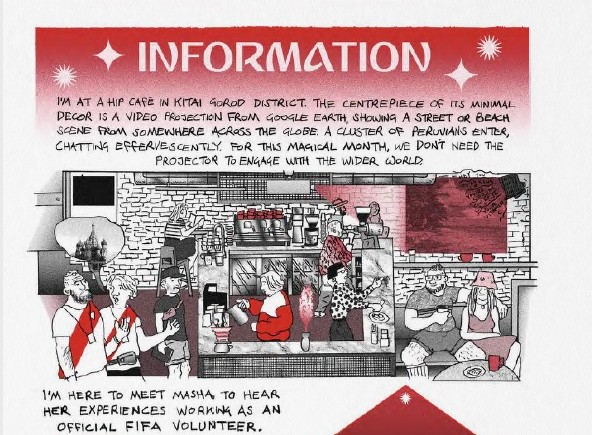

“A World Cup is more akin to a party than a tournament,” Rainbow notes in another of his inter-chapter essays. An excuse for a party is an opportunity for observation beyond the normal bounds of everyday life. Their Russia therefore takes in the middle-aged women selling dried fish at train stops, bear-like men swilling vodka and making friendly-yet-aggressive inquiries such as “why don’t you English like salt on bread?”, while hipsters watch the game in trendy bars where they remain “clean cut and abstemious.” The pair’s cultural tourism is insightful, and frequently riotously funny. This is a footie tournament, after all; various bodily fluids flow forth unbidden, and libidinal impulses of all sorts pursued (often simultaneously, to varying results; a pissed Portugese fan pulling on a Metro significantly more successful than a peacocking middle-aged lothario on the aforementioned nudist beach).

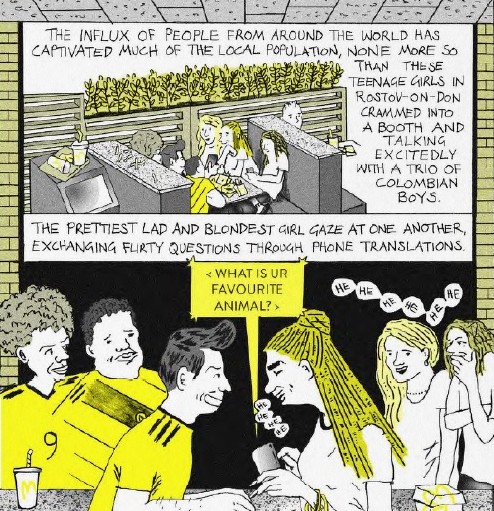

It probably goes without saying (especially with the attached excerpts from the book; you have eyes) that each are immensely accomplished cartoonists. A World Cup Journal makes use of pencil caricature, cut outs, photo montage, superflat monochromatic page layouts, and wonderfully abstracted depictions of stadiums across double-page spreads. A foosball tournament between young fans is rendered in smudged ink wash, capturing the rabid movements of the energetic kids. The single-page structure is broken up further with other portraits: Swedish and German fans nervously watching the game in a pub in Sochi, a girl swinging on the arm of Zabivaka (the tournament’s mascot), armed police on horseback framed by trees and the towers of Moscow’s Red Square.

The distasteful realities of Russia and football’s ruling classes hover in the background always, most often present — as on the periphery of vision or thought — in the footnotes which appear at the bottom of each entry. Sometimes these can be wholly explanatory, as when various aged British players-turned-commentators make cameo appearances, or when specifics of the Russian language or culture need explicating. In others, they serve to undercut comic moments with a dose of reality, as when a scene of teenage girls flirting across the language barrier with Colombian lads in McDonalds is paired with the warnings against couplating with foreigners, especially of a different race, made by the government’s Committee for Families in the run up to the tournament.

The Overton window of acceptability has shifted considerably with the 2022 World Cup, where it’s reported hundreds of migrant workers died constructing the very stadiums millions are watching their teams play in. Questions of human rights abuses and LGBTQ+ oppression had begun already in Russia, as noted in one entry of World Cup Diary that’s emblematic of this whole exercise. At a meeting of FARE, the Football Against Racism in Europe network, an attendee demands accountability for Mohamed Salah having his photo taken with Chechnyan despot Ramzan Kadyrov. His request is interrupted by his bumping into a FIFA-employed cameraman, and so passes with comment. A moment where all the alternate realities of football fandom converge: community, commerce, comedy, and corruption, captured in a few small frames.

William Goldsmith and Christopher Rainbow • Sputnikat Press, £26.00

Review by Tom Baker