Describing her work as examining “first world city life as a second generation Pakistani Muslim migrant” Sabba Khan is the last of our 2017 Broken Frontier ‘Six Small Press Creators to Watch‘ to feature in their own spotlight interview here at BF. A creator who has been involved in the London small press scene for a number of years, her practice has seen an emphasis on focused autobiographical comics in recent years. She has also contributed to zines and anthologies including OOMK and One Beat Zines.

Last year Sabba’s art was exhibited at the hugely popular Burnt Roti ‘The Beauty of Being British Asian’ exhibition in London – the only comics work on show there. Today at BF I chat with her about her architectural background, the cultural themes she explores in her narratives, and the inherent responsibilities in autobiographical material…

ANDY OLIVER: Before we talk about your comics work can you elaborate on your wider artistic practice and the many mediums you’ve worked in from illustration and sculpture to video and architectural drawing?

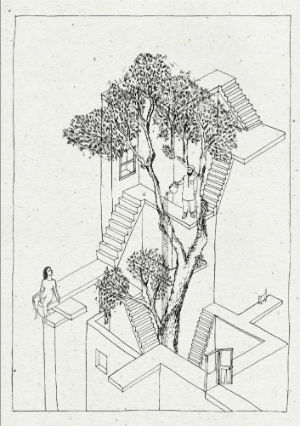

SABBA KHAN: It all began with an art foundation at Central Saint Martin’s and my teenage self carrying a huge amount of uncertainty and confusion. I knew I wanted to do something creative but had no idea exactly what. I was also one of the first in my family to go to university so the pressure of doing something ‘useful’ and ‘job worthy’ was definitely a tangible thing. I ended up studying architecture for 6 years. For better or for worse, my architectural training has become the backbone of everything I do. It’s taught me to think across multiple disciplines in different scales; micro and macro all at the same time.

SABBA KHAN: It all began with an art foundation at Central Saint Martin’s and my teenage self carrying a huge amount of uncertainty and confusion. I knew I wanted to do something creative but had no idea exactly what. I was also one of the first in my family to go to university so the pressure of doing something ‘useful’ and ‘job worthy’ was definitely a tangible thing. I ended up studying architecture for 6 years. For better or for worse, my architectural training has become the backbone of everything I do. It’s taught me to think across multiple disciplines in different scales; micro and macro all at the same time.

Of my past work, I feel ‘A Room of Ones Own’ (AROOO) was a good example of my cross-disciplinary approach. AROOO was an interactive crowd-funded collaborative project with Alternative Press that sought to bring illustration, public engagement and architecture together for International Women’s Day. It started off as a sculptural piece that people were invited to write and draw on, which later took on jewellery, animation and zine-making to share the story. Playing across scales, the piece was able to tap into multiple forms of expression. You were able to write on it, wear it and read it. And that’s what I loved about it.

The hope is to, one day, bring a similar approach to some of the autobio stuff I’m doing now. I once went to an immersive graphic-novel-turned-installation by Juliet Sugg. It was absolutely incredible and offered me a window of possibilities into my own work. In one moment in time, all possible creative forms of expression; illustration, art, poetry, performance and installation came together to tell the story. It was breathtaking.

I first came across your comics a few years back at one of the Comica Comikets when I picked up The Boy & the Owl, your very tactile collaboration with Paul Jacob Naylor. Some of your first comics work, including Bob the Goldfish (above), was more directly allegorical in nature in comparison to your later offerings. What were some of the themes of that earlier output?

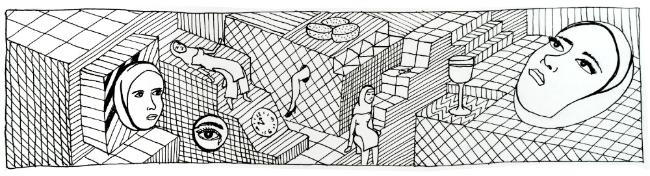

My earlier work explored wider philosophical and existential themes without the pressures of entering a serious and politicised dialogue with the reader. The Boy & The Owl was a children’s nursery rhyme that explored visual metaphors within an orientalist framework; the Boy represented the West and the Owl, the East. Whilst Bob the Goldfish searched the meaning and purpose of life, what it means to search for happiness and the extent we can go, all within a conveniently detached anthropomorphised character.

Both of these, including other zines on Death and Time, were a space for me to pace out my thoughts within a storytelling framework. I was also younger, living off my parents and studying at University, so I look back at these earlier works with a fond nostalgia, almost of happy times gone by when I didn’t really have to think about my voice in the context of the now.

You describe your work as examining “first world city life as a second generation Pakistani Muslim migrant”. Can you tell us about how you use comics to explore those ideas of place, identity and memory that abound in your practice?

I’m my mother’s daughter, and a child of post-colonial economic migration. Born into a first world city as a working class ethnic minority. It’s said that you carry seven generations of your heritage with you… and I really feel that.

My mum tells me that I’m very much like her grandma. My great grandma. She loved making things, and the more detailed it was the more she’d find joy from it. I sometimes wonder if my great grandma were here what choices she would make? Only four generations apart, yet our worlds must be so foreign to each other. This is the migrant experience; change, uprooting, conflict.

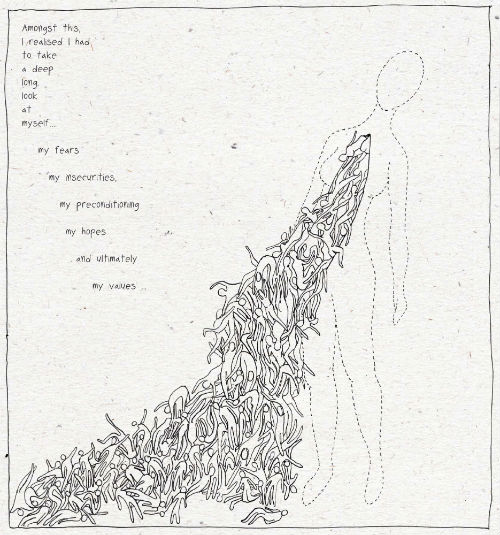

My latest work attempts to make peace with this paradigm. Of opening a window into a very private world where conflicting ideals have sat side by side each other. My work tries to grapple with various lenses – of experiencing racism, of living with patriarchy, of adopting western feminist ideals, of questioning the source of morality, and the reasons behind why I do what I do. I could go on, but I’ll stop here. I think ultimately, things are no longer just a duality for me. I want my work to move toward a plurality. Its not just east/west, white/black, right/wrong. That’s too simplistic.

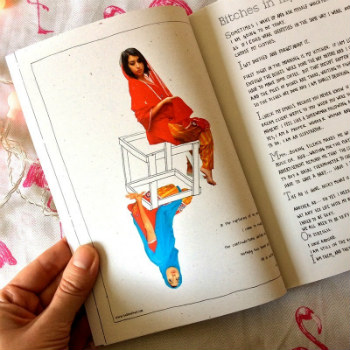

‘The Box of Contradictions’ (above and below) – your short story in the One Beat Zines anthology Identity – was a compelling study of the pull of two cultures on your sense of self. Is there a sense of vulnerability in putting such personal autobiographical work out there? And what are the particular responsibilities surrounding autobiographical work as a creator?

It’s THE one major thing that gives me writer’s block, artist’s block, throws me off my tracks and makes me want to go and hide under the duvet!

It’s THE one major thing that gives me writer’s block, artist’s block, throws me off my tracks and makes me want to go and hide under the duvet!

Autobiographical work is always sensitive in nature – it’s a window into the author’s private world, a world framed by their lens. The responsibility of the author is in recognising the world that is being exposed is not solely theirs. It’s a shared place, often with the people they hold most dearly.

I try to do justice to all the supporting characters in my story. For example, my work often explores the relationship with my mum. It’s easy to give her a character and a voice that is only framed by my own viewpoint. Sometimes it’s frightening to think that I have chosen to represent someone who has their own agency, and I’m recounting their motives from my own perspective. I have to be mindful to handle this power as a narrator responsibly. I find myself constantly working and reworking my words, in defining that line, to not speak for her….

I am acutely aware that my particular autobiographic work has wider connotations within the current global dialogue on immigration and the place of minority communities within a host culture; Trumpism, terror threats, Brexit, etc, etc.

One of my biggest challenges is navigating all the noise that is currently out there on this front. I often find myself slipping into a media-influenced narrative that reads like an agenda. Am I the angry person of faith upholding the right to practice my faith in whichever way I choose fit? Or am I the free speech advocate who thinks we should condemn practices that hinder civil rights and democracy?

I find both of these voices extreme and, most often, unwilling to engage in dialogue with each other. For me, it is important to not approach my work with an agenda. I want my work to do more than uphold a single narrative. I like to see my work as an enquiry into the nature of self. A space where I can invite the reader into a dialogue where nothing is black and white… where we can ask questions and ponder over what makes us all different from each other, and what makes us all human…

Because of this, one of the biggest reservations on my part has been in making my work publicly accessible. As a female cultural Muslim humanist in an inter-racial relationship, I am aware that my work is susceptible to getting misunderstood, taken out of context or appropriated for the wrong cause. So far this hasn’t happened, and to be honest I’m not quite sure what I’d do if it did… But let’s touch wood and hope that doesn’t happen!

You also contributed the graphic narrative ‘The Vagina Dialogues’ in One Beat Zines’ Performance anthology with Amneet Johal. How did that collaboration and its more free-flowing, conversational approach to its subject matter come about?

Amneet and I were asked to do a collaborative response to the Performance anthology. We we had lots of opinions on the matter and ways to approach it. After some back and forth, we eventually realised that the conversations we shared over the months leading up to the submission deadline – in person, and via email and text – was what excited us the most and therefore our strongest source of inspiration. We ultimately came to ask ‘is gender performitvity ever a fixed thing? Is it something that can be truly captured?’ Deciding no, we then instead set about capturing what we could – and that was our dialogue! What resulted was a series of open-ended questions and thought provokers on the idea of playing gender; directly inspired by a transcription of one of our recorded conversations. For the both of us gender is inextricably linked to race . Both feed each other – so it is very challenging to draw the line between the two.

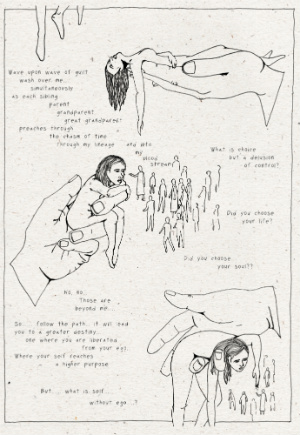

Your use of powerful visual metaphor is one of the most memorable aspects of your comics. What was is it about the narrative possibilities of comics as a form that appealed to you the most as a vehicle for your storytelling?

The most exciting aspect of comics for me is the space in between the words and the illustrations. For me that third space is for the reader to conquer and define. I use visual metaphors as a device to encourage engagement with my work, to show that the words and illustrations are suggestive and open-ended and that nothing is fixed.

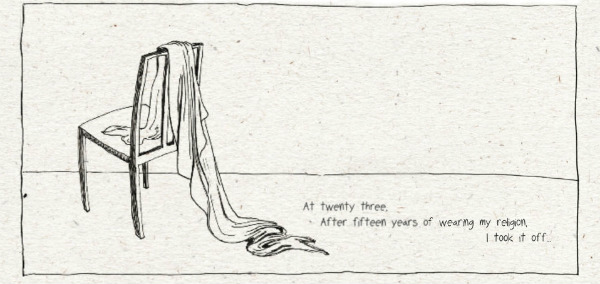

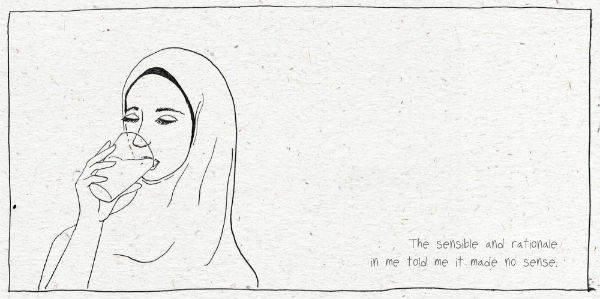

An example suggestive moment in one of my shorts, ‘Determination’ (above) – I look at Ramadan and abstaining from food and water. The biggest challenge for all Muslims is dehydration and lack of water. So when it came to talking about my rebellious ‘breaking fast’ outside of the permissible times, I drew on the idea of drinking water; so simple, primitive and instinctive. Something I’ve seen grown Muslim men do in back alleys during summer Ramadans. That sweet pleasure of quenching one’s thirst made taboo during that one month, and here I am… drinking from that cup…

There’s a lot that is implied in this one moment, so much so that I really felt like I didn’t need to write or draw much to labour the complexity of what was at stake in that moment of time.

You’ve contributed to a number of anthologies over the years both inside and outside of comics including OOMK and those books from One Beat Zines. How vital are those group projects as a self-publisher in raising your profile and sharing practice with your peers?

That’s the great thing about responding to an anthology or a group call-out. It’s important to see personal work in a larger context. My work is extremely solitary, and I often find myself stuck in my past memories and future projections. By putting my work out there and sharing it amongst peers doing similar things I am forced to be so much more present with my work. I also quite enjoy sharing my work across different platforms. It’s a great way of experimenting with different audiences who offer a range of responses. It keeps me on my toes.

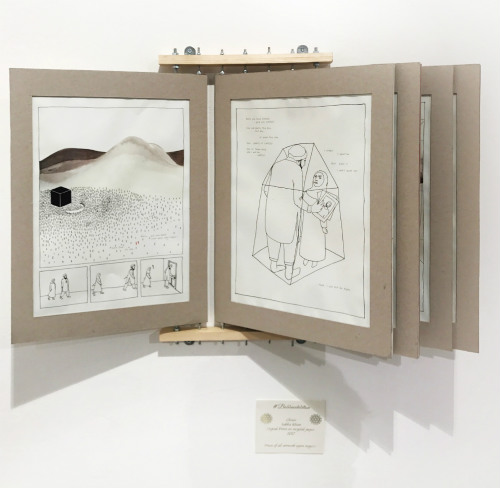

Last summer you had the only comic work to be featured in ‘The Beauty of Being British Asian’ (above and below) exhibition in London with your story ‘Choice’. How did you become involved with that project? And what were the themes that you touched on in that piece?

I had been familiar with Burnt Roti‘s articles through their online magazine, and jumped at the chance of a more visual artistic collaboration with them. The title of the exhibition hit a chord with me. The theme itself was based on a poem by Nikita Marwaha and artists were invited to respond to one of the lines of the poem. I chose ‘The Beauty of Being British Asian is having the freedom to chose your partner when your parents didn’t’.

I wanted to use this piece as an opportunity to really interrogate the idea of ‘choice’. What does it mean to choose your own partner? Did I really choose or is it only because my framework is entirely different to that of my parents that I think it’s a choice? In the end both my parents and I have ultimately conformed to the majority view of the societies that have surrounded us – it’s just that the path I have taken is different. I try to keep this in mind when I work, it is very important for me that I do not devalue the journey my parents and similar migrant groups have taken.

I wanted to use this piece as an opportunity to really interrogate the idea of ‘choice’. What does it mean to choose your own partner? Did I really choose or is it only because my framework is entirely different to that of my parents that I think it’s a choice? In the end both my parents and I have ultimately conformed to the majority view of the societies that have surrounded us – it’s just that the path I have taken is different. I try to keep this in mind when I work, it is very important for me that I do not devalue the journey my parents and similar migrant groups have taken.

In comics like the aforementioned ‘Determination’ – on your relationship with Ramadan – and ‘Choice’ there’s a sense of personal reconciliation and optimism to your art. Is there something cathartic about exploring these ideas on the comics page?

Yes, In my twenties, I had a series of challenging life experiences and epiphany moments that led me to a point where I felt isolated, misunderstood and deeply lost. A lot of things came to a head at varying points, and I realised that my experience and my thoughts are something of a curiosity (put nicely), both within my Pakistani community and my western community. This naturally further reinforced the feeling of isolation. Not only was mine a class, gender and race struggle, it was also one of faith.

Books, lectures, videos and articles, I sponged them all up in order to understand what I was going through. I flitted through theories, discourses and movements… and though each of them spoke to a part of me, there were none that spoke to the whole of me. (Actually I’m using past tense, but it’s still very much an ongoing pursuit!) I’m realising, that what I’m experiencing is the essence of human experience. My experience is mine alone, bound to my physiological make up and my unique circumstances.

This is what I’m ultimately exploring – the space of reconciliation with the elements of my life that have been at odds with each other.

Do you have any plans for self-publishing some of your recent comics in a collected edition?

Do you have any plans for self-publishing some of your recent comics in a collected edition?

Yes, the ultimate aim is to compose a selection of short stories into a larger body of work that all pivot around the central themes of belonging and identity. However, short term, a smaller ‘taster’ self-published book is definitely the next step. So stay tuned!

And, finally, what’s next for Sabba Khan? Are there any other projects you’re working on this year that you can tell us about?

In addition to my comics, I’m also currently working with my partner on joint architectural projects, one of which is our home. These projects really feed into my wider practice and my sense of self, especially our house, where we are very much in the midst of redefining ‘home’ for ourselves. We often find ourselves asking; what is the kind of space we want to live in? How can it offer both security and comfort whilst at the same time enabling new possibilities of being? It’s really exciting and great to work on physical, spatial things that have an immediate impact on your life. You’ll see a lot more house-related photos on my Instagram feed this year… Just to warn you!

For more on the work of Sabba Khan visit her site here and follow her on Twitter here. You can visit her online store here.

For regular updates on all things small press follow Andy Oliver on Twitter here.