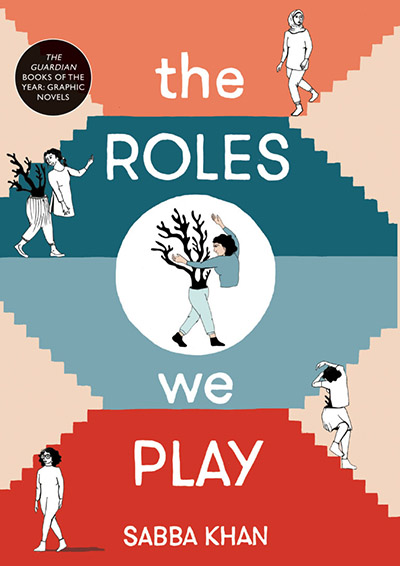

It’s been quite a while since I last chatted with Sabba Khan here at Broken Frontier and, in the intervening years, our 2017 Broken Frontier ‘Six to Watch‘ artist has gone on to widespread acclaim for her first long-form comics work, the graphic memoir The Roles We Play from Myriad Editions (published as What’s Home, Mum? by Street Noise Books in the US last year).

The book is described as “a vivid snapshot of contemporary British Asian life… investigat[ing] the complex shifts experienced by different generations within migrant communities” on the Myriad site, and it has gone on to win a number of awards since publication. I chat to Sabba today about the road to publication, the responsibilities of autobiographical work, and the power of visual metaphor…

The book is described as “a vivid snapshot of contemporary British Asian life… investigat[ing] the complex shifts experienced by different generations within migrant communities” on the Myriad site, and it has gone on to win a number of awards since publication. I chat to Sabba today about the road to publication, the responsibilities of autobiographical work, and the power of visual metaphor…

ANDY OLIVER: The last time we spoke about your work it was long before The Roles We Play had been picked up by Myriad. But even at that point you’d produced small press practice that laid the foundations for the book. Can you give us a potted history of the book’s evolving journey to publication from a One Beat Zines short story to the (then) Myriad First Graphic Novel Competition and beyond?

SABBA KHAN: The Roles We Play started off as a 6-page piece I did for One Beat Zines’ anthology titled Identity back in 2015. It took me 6 months to produce those 6 pages. In those pages, I developed a visual style, a tone of voice and a purpose. I knew then it needed to be more than just those 6 pages. It had legs. But I was terrified.

So I started small. For my next steps I wanted to celebrate a positive side of my religion, as those first 6 pages spoke a lot about my issues with it. So during Ramadan, I did another short piece that I shared on a website called ‘Interfaith Ramadan’. After that, I contributed a third piece to the group exhibition ‘The Beauty of Being British Asian’ curated and put together by Burnt Roti mag.

This piece explored ideas around choosing your life partner, arranged marriages, and upholding familial traditions. I constructed it as oversized framed book, which once hung, visitors were asked to flick through and read – emulating the personal/individual book experience in a gallery space – it ended up with its own mini queues on the opening night! After that I found myself with 3 short stories, and my mind was bursting with more – I couldn’t contain myself, something was being unleashed.

I started drafting story after story – some would make themselves known in visual form very quickly, others took much more cajoling. I was supported and held by my friends and my partner, and they urged me to apply to Myriad’s first graphic novel competition in 2018. I did. I was shortlisted, and then subsequently I was given a publishing deal. End of 2018 I started my journey with psychotherapy which would go on to emotionally and mentally support me for the next 2 years.

In 2019, I got funding from Jerwood Arts, which enabled me to work on the graphic novel during daytime hours. I left my design agency job and became fully self-employed a month before Covid-19 hit the news. Once complete the graphic novel was published in July 2021. It went on to win Broken Frontier’s Breakout Talent Award, Guardian’s Best Books of 2021, and then the next year it won the Jhalak Prize, in addition to getting shortlisted for numerous other awards. It is now also published in the US under the title What is Home, Mum?.

AO: For readers who are unaware of The Roles We Play/What is Home, Mum? how would you describe it in terms of the themes you explore in the book and its subject matter as a graphic memoir?

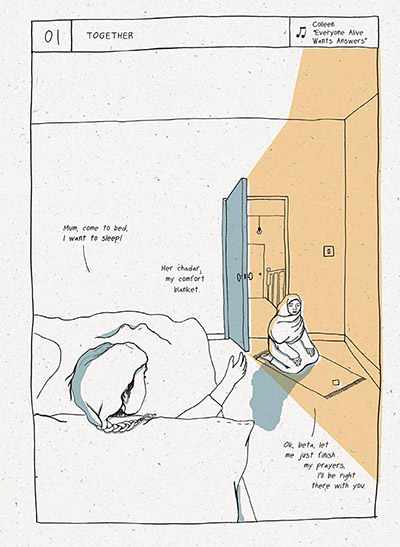

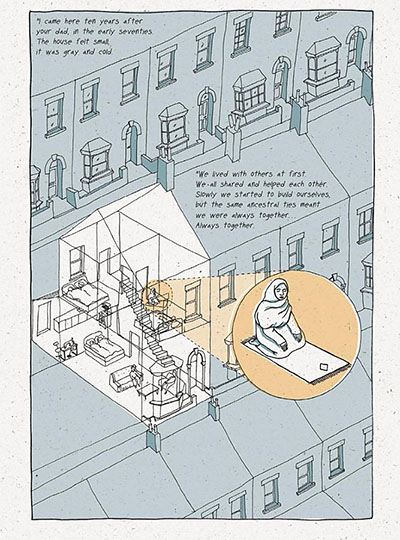

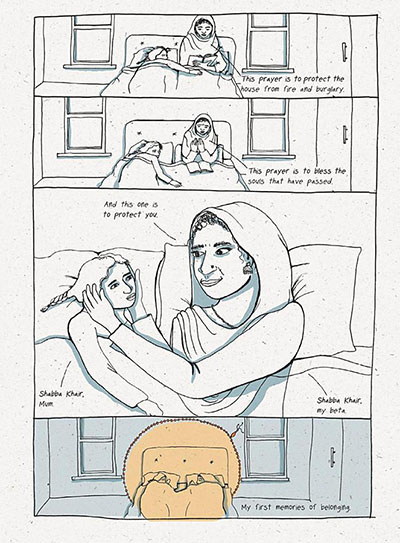

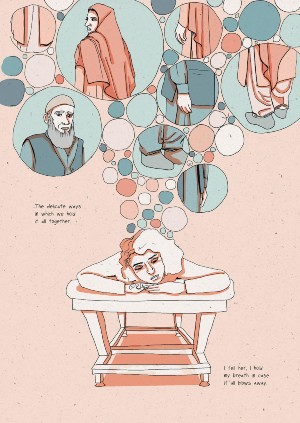

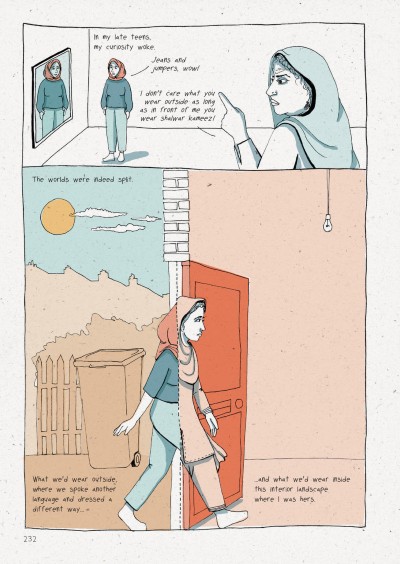

KHAN: The book is a-bit genre-defying. It uses lived experience as a starting point but then expands from that to become a critical essay on contemporary diaspora experiences. It makes space for both the personal and the private, and the political and social. I consciously constructed it this way; the main chapters use memories, flashbacks and past experiences as a vehicle to talk about lived experience, and then the narrator pages, these soft pink borderless spaces (which I describe as internal and womb-like) are where the present day, critical, zooming-out, contextualising voice takes place.

The book explores my relationship with faith, my family’s migration history, my co-dependence with my mum, maternal narcissism, psychotherapy, familial structures, racism, Islamophobia, realities of multiculturalism, living in Newham in East London, the onion layers of othering as a Mirpuri second generation immigrant. Lots of things.

AO: I’ve asked you this before at BF but I think it’s a question worth revisiting given the long-form nature of The Roles We Play and the raw candour of your narrative voice. So how did you approach the extra responsibilities of autobio given the very personal nature of a book that is fundamentally about family and identity, and how did you cope with the inevitable feelings of vulnerability about committing those experiences to the page?

KHAN: Whilst working on the book, I gifted myself psychotherapy sessions for the first time in my life, and I was absolutely blown away. It’s so beautiful to think that though we are all individuals and our experiences are entirely unique, there are certain mental patterns and ways our insecurities manifest that are shared, and these can be studied, discussed and dissected. This is essentially the role of the psychotherapist.

How incredible, to have a practitioner that has access to not only your thoughts, but can harness the power of all minds, to understand and regulate how our minds work. Its powerful stuff. Yes of course, the critique of psychotherapy is that it can be very Eurocentric and misogynistic, but it also allows you to move beyond the specificity of your own personal mind to a shared place, and that is very comforting.

For example; I’m not the only one who suffers co-dependency with my mum. The way it has manifest will be entirely unique to me, but the outcomes, the way it shows up will be similar to someone else with the same scenario. This allowed me to lean into my specificity, but I also made sure I leaned out of it. At each point I knew I had to move to the place of common humanity. What were the elements about my experiences that make it universal? That’s what stopped the body of work from being a navel gazing misery memoir, to something much more transcendental, if I may say so myself.

There was a lot of thought that went into how I dealt with stories from other members of my family. I did a safe-guarding workshop at PositiveNegatives, where I realised I needed parameters and a process to how I used my mother’s story in the chapter that explores my family’s migration. I had to make sure she knew what I was doing and the context her story would sit in. I had several rounds of informal interviews with her that fed into the final piece. Once it was complete, I translated it back to her so she could understand how I had delivered her story. She was happy with it, other than the size of the rocks! ( I had drawn them too big). In a similar way, I showed my uncle the chapter where he features, and I also corroborated stories with my dad. These were important steps in taking responsibility for other people’s stories.

The moments where I spoke about my sister were even trickier. At the time of writing my book, I was not in much communication with her, which made it difficult to sense check, or even know if it was the right thing to do or not on an ethical level. I ultimately knew I couldn’t go into her story, as it wasn’t mine to tell. But what she went through had affected me, so I mentioned it loosely, suggestively. This allowed me to not over explain which I think can often become a trap people of colour fall into when trying to address the white reader.

I found that those who understood the cultural, familial backdrop didn’t need much information and could gather a lot from the little I mentioned. Those that didn’t have the contextual understanding perhaps were not able to read as much into it. And I think that worked for me. It allowed the book to be read as deeply as the reader was able to go.

There’s also a lot I didn’t put in the book. A lot of people feel like it was very personal, but all I could see, at least initially, was all that I edited out, where I practiced restraint and where I kept myself and my family protected. Again, I think this feeds into how far readers are able to go. For example, there is only a single page in the whole 280 pages where I overtly suggest domestic violence.

After two years of the book being published, the people who have picked out that page are the readers who understand how difficult it was for me to share that. How so much of the control shown across the book is only ever suggestive of an abusive control. I didn’t spell it out, but then I didn’t need to for those who would understand the cues. And as such, it doesn’t feel as vulnerable or exposing as it could’ve been.

I guess for me, I got more interested in the consequences and impact of life experiences rather than the experiences themselves, and that’s what helped me zoom out of the specifties and lean into the universal.

AO: One of the reasons the book connects so profoundly with its readership is your careful use of visual metaphor. Why did that work so well for you as a storytelling tool to communicate with your readership?

KHAN: The visual storytelling allowed me to show things rather than describe things. This fed into the suggestive, open-ended, interpretive nature of the book. I was able to invite the reader in, to bring themselves into the story and to be active participants in the shaping of the story. For example, one of my favourite pages in the book, is a double paged spread, of very few lines, almost empty, the frame forms a cliff edge, and the protagonist (me!) stands on the edge, looking down. There is a single word; ‘nothing’. This is her response after her mum asks her what happened after a racist attack takes place. Another example; where the dam fills up, the whole page is filled with water, the Himalayan mountains skimming the top surface, just my mum’s family left to witness the devastation.

Each of the chapters in the book centres around a memory or a pivotal realisation. The memory itself will go through a range of peaks and troughs, so it was up to me to show the pacing through the way I use the page. Big moments are expressed through double-page, single-panel spreads, whilst quick dialogue, fast action, is expressed with narrow, smaller panels. Comics for me lie in the intersection of reading and watching film. The comic looks and behaves like a book, but is consumed quickly like a film. The construction of the pages, the visuals, needed to reflect that.

AO: You worked with Myriad’s Corinne Pearlman (a Broken Frontier Hall of Fame entrant) as your editor on The Roles We Play. How did Corinne’s input help you shape the direction of the book?

KHAN: For the most part of the process Corinne gave me space to just get on with it. I think she didn’t want to interfere too much whilst I was in the thick of it. Looking back, I really appreciate that. I realise she could’ve been a lot more hands on, which would have made me feel less confident about myself. She stepped in mainly toward the end, where she helped get the overall experience of the story down.

Toward the end, I suddenly had about 34 chapters, with 36 narrator pages, and the structure I had worked with until then became almost like a Rubik’s Cube, it became chaos, unhinged, moving, shifting, changing, things done at the end were moved to the beginning and vice versa. We both knew we had it, it just needed that final moulding and getting into shape. We ended with 30 chapters and 30 narrator pages. I really appreciated that final bird’s eye view that she offered.

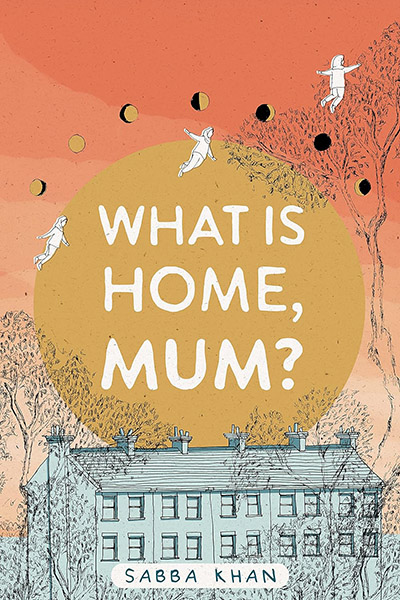

AO: The Roles We Play was published last year in the US under the alternate title What is Home, Mum?. How did the project come to Street Noise Books?

KHAN: We were a few months into the publication of the UK title. It hadn’t yet started to get much recognition when Liz from Street Noise got interested in the book. It was a tricky decision to make, as the UK title and cover were done before the book was complete, for publicity and promotion within the UK. We thought perhaps with a new title we could be a bit more specific for the American audience. The book itself is exactly the same except for American spellings. The title uses the words ‘Home’ and ‘Mum’ to make it clear to American audiences that the book is about belonging and identity and family. The UK spelling of the word ‘mum’ nods to its origins.

Once the UK title started getting more notoriety, I think the publisher realised the title should’ve stayed the same though this has never been said out aloud! I guess you live and you learn. I really did think the book was going to mostly go unnoticed, and stay within the comics circles at best. It far exceeded my expectations. I really love the front cover of the US version – this is actually the book plate design I did for the UK’s first 100 copies sold, and it was printed on gold paper to make it extra special. For me, the artwork really sums up how I wanted to capture the essence of the book – magical, transcendental, visibly Muslim, but also ordinary and mundane with the terraced houses.

AO: Given what a powerful book it is what have been some of the most important reactions to it from readers been for you?

KHAN: I have hundreds of saved screenshots on my phone in a folder called ‘GN Love <3’ which include messages, reviews, and articles of my book. I go to this folder whenever I need to be reminded of the impact of the book. The last page of the book, after having poured my heart out, shares a link to my social media handles and my website. I ask for people to get in touch with me to tell me what they think. And ever since it got published, I get messages regularly.

I try to respond to every one. I wrote the book because I wanted to feel less isolated in my experiences, I wanted to connect, I wanted to invite people to also share. So every message means so much to me. The best ones are the private DMs on my instagram, where someone has just finished the book, or are in the middle of reading it, they are feverish and excited and not quite sure what they have in their hands, but they can relate, and suddenly their world is opening up, and they can see all the connections in their own lives. Those are the ones that leave me feeling warm and fuzzy and cosy.

AO: Talk to us about your creative process. What mediums do you work in?

KHAN: I start off with lots of brainstorming, collating of concepts and visual approaches. Often my work will centre an experience or an emotion, I try to tap into what that is. That is usually the starting point. I will then write around this experience. As the writing starts to shape up, I will begin to think about the visual approach. There may be a few key moments that I need to get across, either fast-paced action to get across a sense of urgency, or perhaps there is a huge weighty moment that needs space.

I get a sense of the pacing down. The visuals start to feed into this. At this stage this will look like rough sketches, thumbnails, experimenting with ways to get across the ideas. This is all so I can reduce the words, so I can cut down. Often I start off with too many words, which, once paired with the visuals, I can whittle down to very little. I enjoy this process. The drawings themselves, for The Roles We Play, I drew by hand on A3 that was then scanned and shrunk to size, with colour added in Photoshop. These days many of my drawings happen on a tablet.

AO: And, finally, what’s next for Sabba Khan? Are there any future comics plans you can tell us about?

I just finished a short story called ‘At the Door’ for Fictionable, where I explore mental health, living in a terraced house, and the spirit realm, and how these three elements are so intertwined within the South Asian culture. (Check it out here).

I’m about to start a big project with the University of Victoria in Canada, looking at survivor-led comics and stories as a way to process and overcome trauma. Expect a lot more of me talking about this in the near future.

I’m also working with a researcher at the Design Museum, looking at alternative and more sustainable ways to manage sewage on the coast of the UK. I’ll be producing a very large illustration that communicates the scale of the problem, from zoomed out arial views to how first person perspective and how proposals can be incorporated into everyday civic life.

Aside from all the commissions, on a personal note, I have also signed up to an agent, and yes I am hoping I still have enough gumption, stamina, sick sadistic pleasure left to do more graphic novels!

Interview by Andy Oliver