In Saint Cole, Noah Van Sciver offers another uncomfortable look at what might be going on in the life and noddle of that bloke taking your pizza order.

While Charles Forsman might be taking the plunge into new generic waters with Revenger, the equally celebrated Noah Van Sciver is, as they say, sticking with his knitting. In Saint Cole, published recently by Fantagraphics, he again dissects the male psyche to offer a characteristically unblinking look at what lurks within.

While Charles Forsman might be taking the plunge into new generic waters with Revenger, the equally celebrated Noah Van Sciver is, as they say, sticking with his knitting. In Saint Cole, published recently by Fantagraphics, he again dissects the male psyche to offer a characteristically unblinking look at what lurks within.

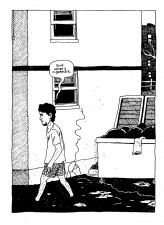

Our protagonist this time round is Joe, a bloke in his late 20s who – naturally – is unhappy with the way his life is turning out. After having an unplanned baby with his partner, Nicole, he’s working endless shifts at a pizza restaurant to pay the bills. However, when he clocks off, he’d rather hang around the bar and ‘take the edge off’ than head home.

When Nicole’s newly homeless mother Angela moves in with the couple, the fuse is lit for an explosive series of events. Angela is a cracking character: rough-edged and often “inappropriate”.

She expresses her regret about falling pregnant with Nicole, and is pleased that her daughter’s “son of a bitch” father is dead. She outlines her worldview with prescience and clarity: “Life boils down to brutality. It’s fucked. Life is brutal and fucked up.”

Wherever you stand on the issue of addiction as an illness, it’s hard to feel much compassion or sympathy for the alcoholic Joe. And I know it’s a cliché, but watching him make terrible decision after terrible decision is like a road accident that you want to turn away from but can’t. There’s something horribly compelling about the trajectory he sets himself on.

(Looking at Joe in the wider context of Van Sciver’s other work, it’s also very easy to see him as a younger version of Harvey, the directionless, responsibility-shirking dad in The Lizard Laughed, a potent one-off published last year by Forsman’s Oily Comics.)

After some shocking developments, the sudden catastrophe of the ending – which puts the book’s title into context – comes as a bit of a shock. However, on second glance it becomes clear that it has been teed up perfectly throughout the book. It’s an audacious tribute to the workings of fate that made me chuckle but also wonder what’s going to come next.

After some shocking developments, the sudden catastrophe of the ending – which puts the book’s title into context – comes as a bit of a shock. However, on second glance it becomes clear that it has been teed up perfectly throughout the book. It’s an audacious tribute to the workings of fate that made me chuckle but also wonder what’s going to come next.

Without wanting to give too much away, there’s a Schrödinger-style lack of resolution to the conclusion: it might solve a lot of Joe’s problems, but it’s certainly going to create a few more.

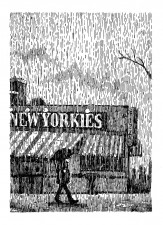

All of this is delivered in Van Sciver’s familiar, ornate neo-underground style. He captures perfectly the down-at-heel environment in which these less-than-aspirational characters play out their drama.

A friend of mine once had a job selling vacuum cleaners door to door, and part of his pitch involved starting to scratch himself (subtly) when talking about all the microscopic nasties that live in your carpet. A lot of Van Sciver’s work has the same effect, leaving you feeling that you want a good wash.

A friend of mine once had a job selling vacuum cleaners door to door, and part of his pitch involved starting to scratch himself (subtly) when talking about all the microscopic nasties that live in your carpet. A lot of Van Sciver’s work has the same effect, leaving you feeling that you want a good wash.

However, apart from that visceral stimulation, he also tweaks the form effectively to describe the various states of intoxication his protagonist staggers through, from the light buzz of a couple of drinks to some altogether more altered states. His richly textured style also enables him to manipulate mood nicely; the rain is a constant, oppressive presence, highlighting Joe’s helplessness and reliance on others.

Noah Van Sciver has a wily narrative intelligence that he weaves subtly into his work under cover of an itchy naturalism. His work may focus on a very particular segment of contemporary life, but his fictions offer a sharper and more resonant X-ray image than any number of diary comics.

Noah Van Sciver (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books, $19.99, January 2015