Holding the hardcover edition of The Labyrinth in 2019 is a special feeling for a number of reasons. For a start, it shouldn’t even be here, given that it will be six decades since it first appeared in print. This wouldn’t matter to a classic work of fiction or non-fiction but is rare in the illustration and graphic space, where styles, colours, and even characters tend to date faster than last year’s big-budget Spider-Man movie.

What gives The Labyrinth legs is the timeless imagination of its creator. Saul Steinberg, who passed away almost exactly two decades ago (May 12, 1999), is best known for changing fridge magnets the world over with a cover he did for The New Yorker titled ‘View of the World from 9th Avenue’. It appeared in 1976, and ended up unleashing imitations, counterfeits and even parodies ever since. He did approximately 600 illustrations for that magazine, helping to create a template it continues to follow. To describe him as an illustrator, however, would be greatly reductive, given his work with theatre, advertising, murals, and even textiles. Shining bright among the gems he strewed liberally across these media and platforms is The Labyrinth.

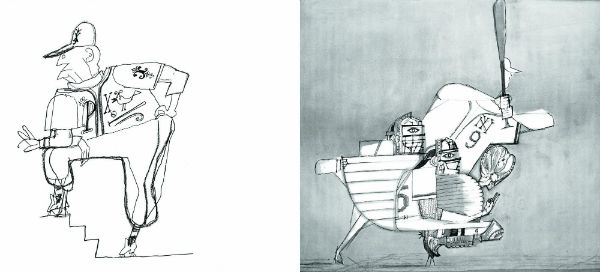

On the one hand, the book works as a ‘Greatest Hits’ collection, offering casual and informed readers a fairly comprehensive look at Steinberg’s prodigious output from rough sketches to published drawings. On the other, it offers an intimate view of the way his mind worked, giving us ringside seats to what seems like a private lecture on history and art.

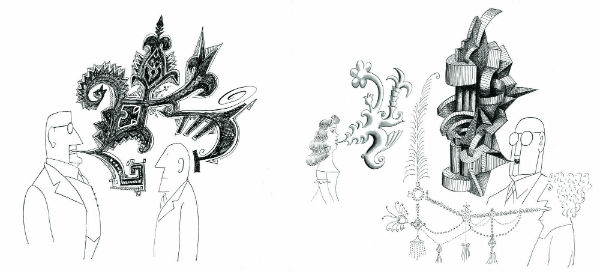

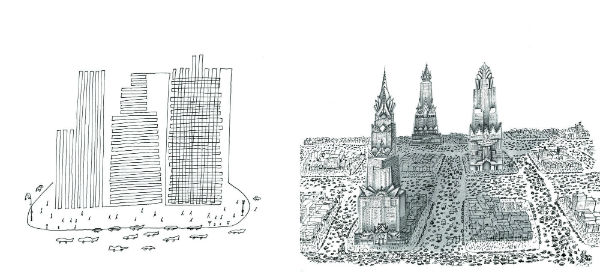

Steinberg shares his worldview by commenting on quotidian events and routine objects, revealing how artists always seek a visual key with which to explain why they alone see something the rest of us cannot. Nothing is too humble or intimidating, and it is in the seemingly simplest figures that he manages to invest the most information. An example is his classic called ‘The Line’, which takes on a life of its own across seven pages. Other pages feature famous landmarks, celebrities and commoners, glimpses of foreign cities he visited, exotic birds, and fantastic caricatures, all products of a restless, inventive mind.

It’s hard to describe Steinberg’s style, even though it jumps out the minute one is trained to spot it. His is a constant struggle between words and images, where existential questions are transformed into visuals we can grasp. These can be consumed in seconds or pored over for days in an attempt to tease out their significance because they are often not what they seem to be. It is also what gives the collection its title because it implies that we are in a maze of multiple meanings, where pulling on a thread can reveal something unexpected.

It’s hard to overestimate the influence Steinberg has had on everything from typography to how graphic novelists create their storyboards, but that influence makes itself felt when some pages suddenly seem familiar even though we haven’t seen them before. There are also shots being fired here, against American consumerism, hypocrisy, and pomposity.

Lastly, the book comes with an introduction by Nicholson Baker and afterword by Harold Rosenberg, both of which help, but both of which are also superfluous in the face of what they hold in between.

Saul Steinberg (W/A) • New York Review Books, $39.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira