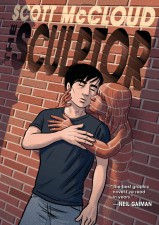

Scott McCloud has secured his legacy in the comic book world through his books on the theory and craft of our medium: Understanding Comics, Reinventing Comic and Making Comics. He also wrote and drew his long-running creator-owned series, Zot! But besides a few experimental projects with long-form comic storytelling, Scott McCloud has never published a true graphic novel.

That’s a gap in his resume that’s about to be filled in a big way with the release of a new, near-500-page graphic novel about a young artist named David Smith who makes a deal with Death so that he can sculpt anything he can imagine. The catch is that he only has 200 days to live, and when he finds his muse and falls in love only days after making the deal, David soon discovers that what he was willing to give up for his art was much more than he bargained for.

I spoke with Scott McCloud just before the release of this book, which took him five years to create. We talked about the pressures of making it, the painstaking process of gathering reference for New York City, and the sacrifices that all artists must make for their art.

So let’s begin with the surprising fact that despite your well-earned status as a legend in the comic book industry, this is actually your first graphic novel.

Scott McCloud: Yes, this is my first attempt at a full-length, self-contained graphic novel. When collected, my old series of Zot! is a book even larger than this one, but those were smaller stories, really a collection of issues and short stories. This one (The Sculptor) is all of the pieces, completely self-contained. Don’t expect any sequels.

Scott McCloud: Yes, this is my first attempt at a full-length, self-contained graphic novel. When collected, my old series of Zot! is a book even larger than this one, but those were smaller stories, really a collection of issues and short stories. This one (The Sculptor) is all of the pieces, completely self-contained. Don’t expect any sequels.

And it took you five years to complete it?

The active making of the thing took five years, but in fact, the idea had been kicking around in my head for decades before that. It’s a very old idea and I gradually realized over the years that it was one of those stories that I let get away. So I arranged to start work on it in the late aughts, and for the next five years that’s all I did for about 11 hours a day, seven days a week, except for the last year where I was working closer to 14 hours a day.

With all your commitments, was it hard to clear that much time in your schedule?

I still did some lectures and workshops during that time, but the vast majority of the time was just me chained to the desk, which for the most part was a surprisingly happy time. I really don’t mind working around the clock if it’s on something I love, and I really loved working on this book.

With all the books you’ve written about understanding and making comics, did you feel a lot of pressure when it came to making your own graphic novel? For example, did you feel that you had to do more than just tell a good story, or that the book had to say something about the industry or the medium itself?

Oh yeah, there was a lot of pressure on me after writing Understanding Comics, but especially after writing Making Comics. That one put a real target on my back because I wasn’t going to have a lot of authority to explain to others how to make comics unless I was capable of making one myself. But I actually kind of relished the pressure. I like the fact that I was forced to give it my all just to meet expectations, much less exceed them. I knew it was going to be an enormously hard job, and something about that appealed to me.

And I had an editor at First Second Books, Mark Siegel, who I think recognized that I like a challenge, and so he challenged me and kept the challenge going all the way through four drafts of the layouts, and then through the years it took to actually draw the finished art.

Did you know it would take you that long going into it?

We agreed that it would be a three-year window and I prayed that it would be enough. But we got ambitious. Mark Siegel and I both got very ambitious with this book and he gave me the space to do the extra work that both of us felt was necessary to help this story achieve its full potential. I was very grateful for that.

While working on the book, did you feel like you and your main character, David Smith, were living parallel lives?

I don’t think there’s any artist in comics who could do a story about an artist without including themselves. There’s definitely some David in me. There’s more of my wife, Ivy, in the character of Meg, however. She inspired that character many years ago and she was a tremendous resource in writing the character. So the lion’s share of David is fictional, but he definitely has some of me in him.

And how much of David’s struggles in the book are meant to represent universal struggles that all artists can relate to?

Some of David’s struggles are particular to David. Some of them are just the product of his own neuroses. But I think, and I hope this is true, that his struggles reflect the universal struggle on the part of artists to make something that will last, something of value to society, or at least of value in the eyes of the artist themselves. Something that isn’t just of its time but that will still be around long after they’re gone.

And this seems to be a very strong theme in the book, that in order to create something great, you must sacrifice your life for your art.

You know, to sacrifice one’s life for one’s art (and it’s a literal sacrifice in my story, but of course isn’t that what we do if we give months or years, or even decades to our art?), we’re sacrificing whole swabs of our lives to making what we make, and I’m sure there have been many artists who’ve faced that tension between art and love, between art and family.

When I was first making comics professionally, I listened a lot to Sunday in the Park with George, the Steven Sondheim musical, because I liked that tension. There was a tension that reflected the tension that Ivy and I had over how I was going to spend my minutes. You know, was I just a workaholic? And I think I had the opportunity to make that sacrifice more literal, more stark. And in doing so I’m hoping that I allowed those themes to be more starkly illuminated. It allowed me to uproot the things that usually lay under the surface and expose them to the light.

That struggle of trying to find that balance is so basic to me. Because you’re living in this theoretical future where your work will hopefully be appreciated beyond your own life span. But that means you’re living outside of life. And life is going on all around you. You’re missing things. Chris Ware writes eloquently – and rather bleakly – about this. He writes about how we work on our… I think he calls them “slow-motion picture stories,” while everyone around us goes about their lives for years, or even decades.

I’m not quite so pessimistic about that because I managed to find that balance despite the fact that I work very hard. When I’m done with a project, Ivy and I, and often the kids, spend quite a lot of time together traveling, lecturing, promoting whatever it is I just finished. When I finished Making Comics back in 2006, we went on tour for an entire year and went to all 50 states. So I’m pretty sure the kids got enough of me for a long time after that.

And I think it’s important to note that in the book, David does struggle with the balance between life and art, but he couldn’t have continued making his art without Meg. Not only did she save his life, but she was his inspiration in a very direct way.

Well, Megan in particular occupies that place as the muse quite thoroughly. I told Ivy that now she has been upgraded to “grade-A” certified muse. I said, “You’ve inspired a character that’s at the center of a work of this ambition. That makes you a Muse with a capital M in the grand tradition of Sarah Bernhardt.” She’s definitely occupying that category now. She’s my muse.

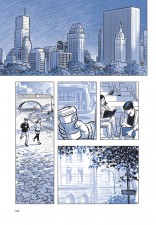

In addition to the supporting cast, New York City itself feels like a character.

Well, New York City was an incredibly important part of the story. And it was, as you said, a character in the story in many respects. It was tremendously important to me that I got New York right. It was a great disadvantage of mine that I lived in California, so I worked very hard to make it out east as often as I could.

Well, New York City was an incredibly important part of the story. And it was, as you said, a character in the story in many respects. It was tremendously important to me that I got New York right. It was a great disadvantage of mine that I lived in California, so I worked very hard to make it out east as often as I could.

I took any opportunity, work or otherwise, to make it to Manhattan. And then I would spend those days just wandering the streets and taking photographs. I took tens or thousands of photographs of New York. I took special advantage of the tagging features in Apple’s iPhoto, so that if I wanted to see only long shots with stark shadows of buildings, or if I wanted to see pictures of pedestrians, or only pictures at night, or only pictures in the rain, I could call those up and that was tremendously valuable. It took a lot of time to tag them, but it saved a lot of time in the long run.

And this allowed me to paint what I hope is a more realistic portrait of the city. I also took great advantage of Google Street View. If I want to have my character walking at 3 AM, as I do, from Williamsburg to Chelsea over the Williamsburg Bridge, then Street View allowed me to realistically depict all the things that he passes along the way. It would have been impractical for me to walk that distance just for that scene, especially at 3 AM. So I’m very grateful that Street View existed just in time for me to be able to do this book.

I also talked to a lot of people about living in Brooklyn and the art world in New York. I just tried to get as many perspectives on what it was like living out there in this day and age. I did my best to represent that faithfully on the page.

In doing this book, how hard was it to draw all of David’s sculptures?

Well, I’ve always liked sculpture just as an average museum-goer, and I suppose over the years there have been different sculptors whose work I’ve enjoyed. But a lot of it just came out of David’s imagination, which of course means my imagination.

Which means you had a double job of being both a comic artist and a sculptor.

Yeah right, that’s true. I did. Although I had one very important advantage, and that is the fact that the sculptures that we see of David’s, that we clearly see, are the sculptures that fail. They are the sculptures that are not embraced by the art world, that do not inspire gallery owners or critics. And in many ways I feel like I’m only qualified to draw those. The work that did get favorably noticed is work that happened before the story began. We only very faintly see in that background.

The work that he does during the story, which really impresses his friend Ollie, we don’t see either. So I felt like I was qualified to draw sculptures that could not make it in the art world. I’d given myself that gift. There was never a chance that I would make them too good, because there was nothing that I could come up with that could not credibly be rejected by any critic or gallery. So I carved out a safe place for myself. It would have been much, much harder to do a story about a sculptor whose work was recognized far and wide as a masterpiece. I don’t think I have it in me to do it either. I don’t think it would have been credible.

Now that the book is done, do you have a big year of touring ahead of you?

Well, yeah. Last year alone we went to China for two weeks. We went to Chile, to Amsterdam, England, Spain, and about 14 other locations here in the US. I taught for two months in Tennessee. And that was all before the book came out.

The book drops here in the United States on February 3rd. It’s coming out in six languages in subsequent weeks, some of them the very same day. And we’re traveling to 14 cities in 16 days here in the US and then it’s off to Europe for events in England, Germany, Italy, France, Spain, and then The Netherlands. We have a number of universities that’ll be bringing me out for this whole visual lecture. So I expect 2015 to be very active.

After that’s done, do you have any plans yet for your next book?

Beyond that, my next book, which will also be coming out from First Second, will be on visual communication. I’m very interested in how pictures communicate, in how pictures teach. And I would like to finally do a book that tries to distill the common principles of visual communication across different disciplines.

I’m very much looking forward to this next book, but first my last book has to let me go. It’s still got a grip on me. There’s still a bit of a tension there as I want to make sure to promote my last book actively. But at the same time, I’m eager to get to the next book as well.

I know Scott McCloud would rather it were forgotten, but his first graphic novel was actually “The New Adventures of Abraham Lincoln” which came out in 1998. I thought it was great fun and enjoyed it very much.