It takes a while to pinpoint what Yamada Murasaki manages to evoke with her pithy stories. It isn’t exactly ennui, but more a lingering dissatisfaction with the status quo as far as the treatment of women is concerned. To refer to her work as feminist is easy but ultimately reductive, although one can see how the artist must have been slotted into that category when she first began creating manga for magazines like COM before moving to the more respected Garo.

Either way, the feeling will be familiar to those who read Talk to My Back, her first collection translated by Ryan Holmberg two years ago. Second Hand Love, also translated by Holmberg, brings us two novellas—A Blue Flame, and the title story—as well as illustrations commissioned for a novel, and an interview with Murasaki from now defunct magazine Advertising Review.

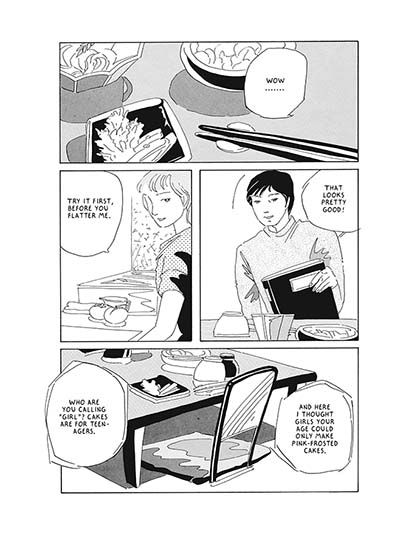

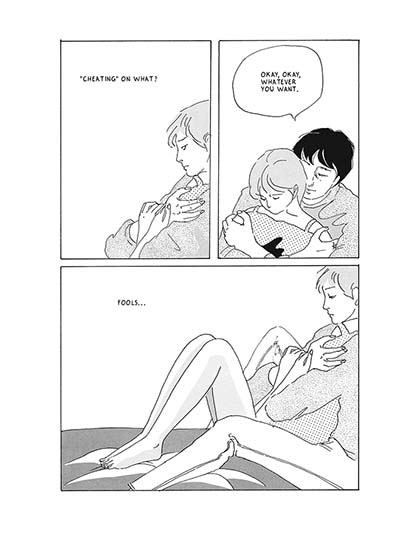

There is a quiet anger in these pages, even if it isn’t immediately obvious. Consider A Blue Flame, about a woman called Emi and her affair with an unnamed married man. Emi isn’t interested in conventional relationships, where marriage feels like a kind of death. It is a sentiment Murasaki echoes in her interview when she speaks of the relief she felt when her own marriage ended after a decade. “Being married made me realize that ultimately I was alone,” she tells her interviewer, “So did having kids.” A startling confession to make in 1985, it is a sentiment that drives Emi’s own need to question what she wants from a man. She recognises that her suitor is, eventually, replaceable by another just like him.

The protagonist of the title story, Yuko, also struggles with relationships, but what she feels is more ambiguous, driven by the knowledge that her father cheated on her mother. To call her empathetic is a bit of a stretch, but one can sense Murasaki trying to navigate her own way around notions of self-worth. Yuko weighs the pros and cons of domesticity and finds it wanting. Where Talk To My Back looked at the life of housewife Chiharu Yamakawa, these novellas are about women on the outside. They are the ones that people like Yamakawa’s absent husband spend a few hours with, allowing Murasaki to explore the contradictions that reside within gender roles prescribed by Japanese society.

There is also a certain ruthlessness to Murasaki’s work, which may come across as innate ability but may more likely be the result of an intense editing process. It is the way her panels use the bare minimum to alight upon a certain emotion, where even the use of space feels carefully planned, the whiteness allowing her clean lines to stand out more effectively.

Second Hand Love is a great collection, not just for anyone interested in alternative manga or the legacy of Garo, but for the access it offers to artists like Murasaki who didn’t get their due and still hover at the margins of manga’s male dominated world. She says as much in the interview, comparing her work to what sells in Japan, while wishing more women would read her.

It is interesting to read Second Hand Love in 2024, months after a survey from the Japan Family Planning Association found that 48.3% of married couples were in sexless marriages, up from 31.9% when the survey started two decades ago. To read some of the reasons cited, such as the few hours of household chores and childcare put in by Japanese men, makes Murasaki’s work seem almost prescient.

Yamada Murasaki (W/A), Ryan Holmberg (T) • Drawn & Quarterly, $24.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira