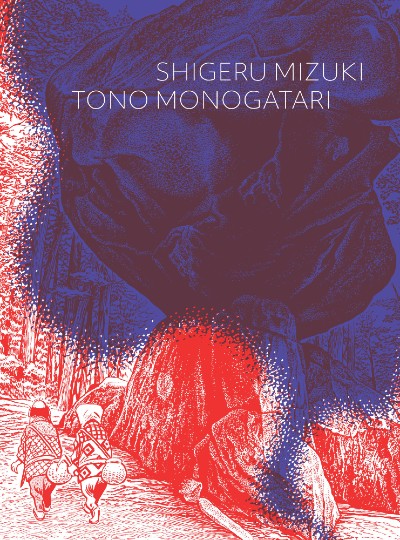

It’s safe to assume Zack Davisson spends as much time in the spirit world as he does in Seattle. It comes with the territory, given his roles as writer, lecturer, manga scholar and, most excitingly, Japanese folklore expert. Davisson introduced English-language readers to the magic of Shigeru Mizuki years ago, and his latest translation — Mizuki’s 2010 version of the supernatural classic Tōno Monogatari (reviewed here at BF) — hit bookstores this month from Drawn & Quarterly.

We had a few questions for Davisson about Japanese horror legends, the challenges for a translator, and what Mizuki thought of his readers outside Japan. Here are his emailed responses:

BROKEN FRONTIER: What emotion do you think Kunio Yanagita was trying to capture with Tōno Monogatari? Does Mizuki’s version follow in that spirit? What challenges does this pose for a translator?

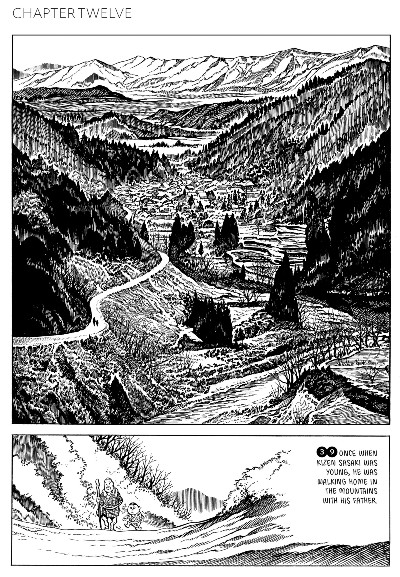

ZACK DAVISSON: I’d say Kunio Yanagita had two things he was trying to achieve with Tōno Monogatari. One was the capturing and preserving of vanishing culture that he saw being displaced by the modernizing of Japan, and two was to establish himself as a writer. Yanagita was writing at a time when there was an active disdain for anything supernatural. Writing in the simplified, straight-forward style he chose was, I think, an attempt to strip fancy from fantasy. He wanted to present these somewhat fantastic stories as a matter-of-fact part of the lives of the people of Tōno.

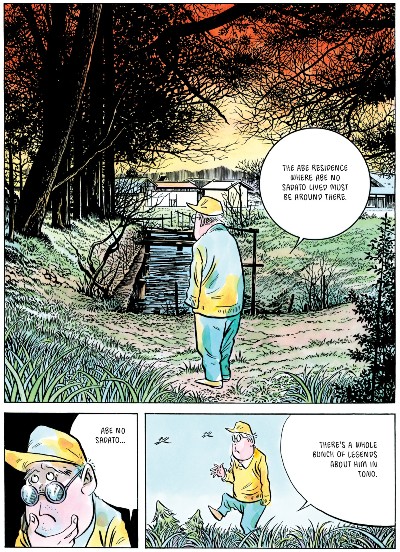

Yanagita’s dry, pragmatic style is the opposite of Shigeru Mizuki’s earthy tones. Mizuki explodes with emotion. Mizuki loves the supernatural and embraces the fancy in the fantasy. I think you can see the push and pull of these two styles in the text. In the beginning, Mizuki is faithful to Yanagita but his patience eventually wears thin, and he starts to explode with emotion on the page.

As a translator, my purpose is always to serve the artist. In this case that means Shigeru Mizuki. This is like when I translate Gou Tanabe’s Lovecraft works. I am not translating Lovecraft; I am translating Tanabe’s interpretation of Lovecraft. It’s the same case with Tōno Monogatari. For those wishing to read Yanagita’s original take I point you to Ronald Morse’s excellent translation. But for mine, I will always be the voice of Mizuki.

BF: Is it simplistic to assume Mizuki was simply trying to reintroduce a new generation of readers to the cultural heritage of Tōno Monogatari?

DAVISSON: I don’t think that was his reason. Tōno Monogatari is extremely famous in Japan and most Japanese people are familiar with at least some of the stories. I’d say it was more about Mizuki’s personal exploration of something he loved. At this stage of his life, he had absolute freedom to do as he wished. And this is what he chose.

Mizuki had been working on similar books for a while, doing his over versions of the great works of Japanese folklore. He produced a version of the 12th century Konjyaku Monogatari. He adapted several of Izumi Kyoka’s stories. I think it was only natural that he would eventually come to Tōno Monogatari, arguably the most important work of Japanese supernatural literature.

BF: I was wondering if you could explain why Japanese horror legends appear to loom so large in that culture as opposed to, say, in the West?

I think part of the answer is in your question. In Japan things like Tōno Monogatari would not be considered horror, per se. There may be frightening or horrific elements, but the stories were not intentionally designed to frighten. In fact, the idea of horror specifically as a form of entertainment did not really exist in Japan until the invention of kabuki theater in the Edo period.

Most of it is that on a foundational level Japan is a country where the supernatural exists everywhere. You can’t walk down a street without seeing shrines that people are actively praying to. When my aunt and mother came to visit me in Japan, they were both amazed at how much these rituals and beliefs were a part of daily life. These legends and stories are a part of the core of the culture of Japan. In fact, I would go so far as to say that you can’t understand Japan without them.

BF: You recently posted an interesting lecture on the yōkai that wards off epidemics. What would you recommend we read in our state of quarantine?

DAVISSON: Clearly the entire works of Shigeru Mizuki, available from Drawn and Quarterly! All of Showa: A History of Japan and Kitaro should keep you busy for a while! Hopefully, we will have some more for you when you get through those.

BF: You have described Mizuki as a sort of mythical figure, a mix of Disney and Eisner. Did you get a chance to interact with him? Did he have an opinion on how readers outside Japan approached his work?

DAVISSON: I met Mizuki once and worked with him mostly through proxies. He was 93-years old when I started translating his work and his family understandably wanted to limit contact. Most of our interactions were when I would send things for approval. One thing I remember is how he talked in baseball metaphors in terms of his work. He considered something like Tōno Monogatari a “curve ball,” less representative of his career on a whole, whereas Kitaro was a “straight pitch.”

I don’t honestly know what he thought of readers outside of Japan, other than I don’t think he thought of them much at all. His life was dedicated to Japan and it was in Japan where he was loved. I think if there was further interest, well, that was fine. But to the best of my knowledge acclaim outside of Japan was not something he actively sought.

I would say he was concerned about his legacy. Mizuki was incredibly multifaceted, and he wanted to be recognized as a complete artist. He said some companies had approached him in the past, but they only wanted to cherry pick the most popular and marketable of his works that would be financially successful. I believe he was happy that Drawn and Quarterly was interested in his breadth as an artist.

BF: This English-language edition took a decade to appear. Does this mean there is more of Mizuki’s work we can expect in the coming years?

DAVISSON: I certainly hope so! I look forward to exploring more of that breadth with Drawn and Quarterly and MizukiPro for years to come!

Interview by Lindsay Pereira