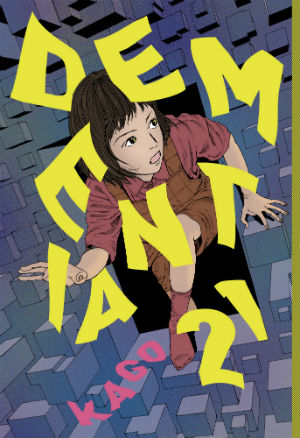

Shintaro Kago’s Dementia 21 is a surprising graphic novel in that it takes his well-known ability to render characters in grotesque situations and uses it as a way to tackle deeply fraught subjects. Perhaps best know for his surreal drawings of vivisected young women, Kago makes an interesting pivot by having the book’s female protagonist Yuki Sakai suffer slight physical violence while being put through an emotional wringer in her service as an elder care assistant. Across seventeen loosely connected episodes we see Yuki struggle to be the best caregiver she can be in the face of ever escalating absurdist obstacles. The nightmare scenarios Yuki faces functioning as a hyperbolic means of discussing the complex questions of a society with an ever-increasing elderly population. By tilting somewhat away from body horror towards comedy and social commentary, Kago has created a book that is charming, hilarious, and thought-provoking.

Each of these short episodes is a playground for Kago to take a premise and stretch it to a fantastical breaking point. Some operate as Tales From The Crypt-style short horror stories with a macabre or ironic twist at the end. In the first episode a coworker jealous of Yuki’s status within the company has her sent to a house where all the previous home health aides have died under mysterious circumstances. But even bandaged and bruised Yuki will still try to retain her employee-of-the-month status. In another, a family facing the decision to cut off life support for a vegetative elderly relative will send Yuki on a descent into the madness of a tubular underworld beneath the hospital when they can’t find the right cord to pull. As a caregiver Yuki will acquire cybernetic dentures for an old man whose abusive daughters broke his previous set to expedite his death. However, in a page out of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the sentient robotic dentures begin taking over the minds and mouth of the man, his daughters, threatening to consume Yuki as well.

Each of these short episodes is a playground for Kago to take a premise and stretch it to a fantastical breaking point. Some operate as Tales From The Crypt-style short horror stories with a macabre or ironic twist at the end. In the first episode a coworker jealous of Yuki’s status within the company has her sent to a house where all the previous home health aides have died under mysterious circumstances. But even bandaged and bruised Yuki will still try to retain her employee-of-the-month status. In another, a family facing the decision to cut off life support for a vegetative elderly relative will send Yuki on a descent into the madness of a tubular underworld beneath the hospital when they can’t find the right cord to pull. As a caregiver Yuki will acquire cybernetic dentures for an old man whose abusive daughters broke his previous set to expedite his death. However, in a page out of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the sentient robotic dentures begin taking over the minds and mouth of the man, his daughters, threatening to consume Yuki as well.

What makes this book so effective is the way in Kago’s Twilight Zone-esque mixing of both pulpy weird-fiction with emotional gravitas. The man with the broken dentures is pitiable, but so are his daughters who inform Yuki that their father’s tyranny lead all three of them to remain unwed. Sadly the only thing that can bring this dysfunctional family together is being turned into hosts for the parasitic dentures eating them alive. Equally sad and strange is an episode in which Yuki is contracted to care for an ever-expanding elderly family inside of the same house. The dark comedy twist reveals that multiple families have been dumping their own aged relatives off at this house to take advantage of Yuki’s elder care skills. When she asks the neglected family members why they allow themselves to be treated this way some pathetically respond that they were just getting in the way back home. Par for the course with Dementia 21, the episode concludes with a body horror twist reminiscent of Junji Ito’s Uzumaki. While the elderly abandoned by their families touches the reader as tragic, it is the story’s bizarre ending that embeds it in the readers mind.

In an interview at the end of the book Kago expresses that he would rather the audience infer his critiques on society from the work itself, yet it is clear that his point of view in Dementia 21 is a decidedly satirical one. He parodies giant monster Kaiju films by having the towering superhero Redman and his alien adversaries unable to do battle because their bodies have become too brittle with age. Yuki helps her client participate in a Battle Royale homage in which the winner is granted a spot in a luxurious rest home. In what feels like an homage to the mysterious post-apocalyptic world of Minetaro Mochizuki’s Dragon Head, Yuki awakens to a foggy ruined world of lost wandering seniors. By playfully packaging his critique of the way society tries to deal with its senior citizen within his parodies of other works Kago disarms the reader. Getting them to laugh and knowingly wink at the reference, but to then grimace in agreement at the very real way in which the infirm bodies of the aged don’t fit well into the machinery of the modern world.

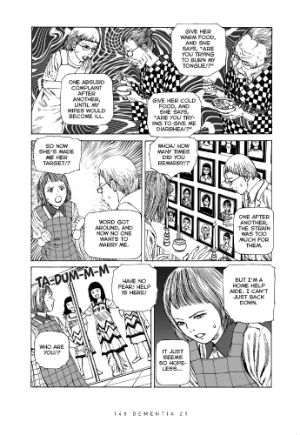

Kago also turns his critical eye towards the elderly, for in multiple episodes they are equal parts agitator to their younger relations. Yuki accompanies one client who refuses to give up driving despite the danger he poses on to a highway that has been build only for seniors. Of course things spiral out of control and the stubborn old man pulls the car onto the even more dangerous drunks drivers only road, escalating to the fugitives only road, and beyond. Another episode has Yuki climbing sky piercing towers meant to warehouse the elderly, tying to locate a client’s lost family member. Her efforts are rebuffed, as locked away in their towers the aged have replicated all the petty squabbles and hierarchical systems of the world below. In a cutting episode, a man’s mother bullies Yuki as she has bullied all of his wives, never content with the level of cleanliness in the house. While Yuki is offered momentary reprieve by a support group against bullying mother-in-laws, but even they collapse under the tyrannical mother’s dirt finding eye. For as much as we see the elderly mistreated so to do we see Yuki having to deal with them being impossible to please. For all her goodwill and effort to accommodate, she is emotionally terrorized in a way that is likely more resonant to the reader than all the supernatural horrors she faces.

That art in Dementia 21 is suitably masterful in keeping with artist of Kago’s caliber. His characters have an exaggerated photorealistic look that works well when he needs to make them ghastly or menacing. With just minor tweaks to cross-hatching and line work on an old person’s face he can transform them a figure that elicits pathos to one of dread. The backgrounds are at times sparse, though always super detailed when rendered. Most hit-and-miss are his computer-effected psychological backgrounds which can be too obvious in their artificiality, especially in comparison to what Kago is more than capable of rendering by hand. Presenting the events depicted in a straightforward manner, his drawings have both the look and feel of more commercial horror and action manga. With Yuki never becoming self-aware of the hoops Kago is having her jump through, and proceeding with the gumption and high spirits typical of a manga heroine. In posing at a surface level as more standard fare, Kago allows for his satire to slip unnoticed in to the hands of less adventurous readers in hopes that his societal critiques may fire in the back of their minds.

It is amazing how much Kago’s message in Dementia 21 translates to a western context. While he has shaped his message for a Japanese audience with Japanese concerns, the cross-generational concerns in the book are also highly cross-cultural. In translating this work and bringing it to the west Fantagraphics has effectively reframed the discussion around Kago. Well established as a visionary illustrator and formalist cartoonist, Dementia 21 proves that he is a cutting satirist with a deft touch for black comedy. That he can combine these with his imagination for the fantastic and absurd is a monument to just how far Kago has honed his craft.

Shintaro Kago (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books $24.99

Review by Robin Enrico