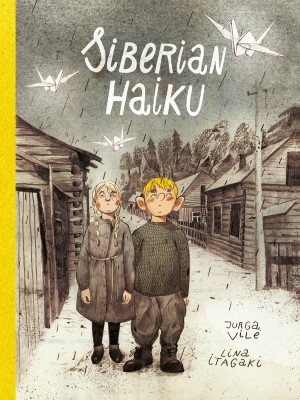

Siberian Haiku is a story written by Jurga Vilé about her father Algis’ memories of being exiled from his home in Lithuania as a child. These tales of exile are brought to life through the exquisite illustrations of Lina Itagaki and superbly manifest the innocence of a child’s viewpoint, channelling the telling of the tale through this gaze. The duo manages to capture the hopelessness and incomprehensibility of being exiled without a chance to protest through this powerful union of experience and imagination.

Siberian Haiku is a story written by Jurga Vilé about her father Algis’ memories of being exiled from his home in Lithuania as a child. These tales of exile are brought to life through the exquisite illustrations of Lina Itagaki and superbly manifest the innocence of a child’s viewpoint, channelling the telling of the tale through this gaze. The duo manages to capture the hopelessness and incomprehensibility of being exiled without a chance to protest through this powerful union of experience and imagination.

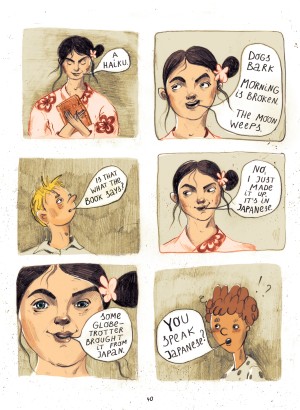

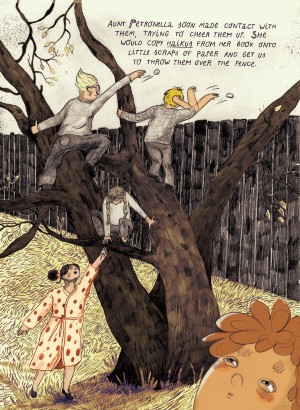

Instead of using the more definitive borders of conventional comic pages, Lina Itagaki’s free-standing illustrations are left open on the pages. These unbounded illustrations perfectly capture the boundlessness of a child’s perspective; simultaneously reminding us of the unreliability of our narrator (through both his limitless imagination and finite understanding of the world), but also his unflinchingly sincere and unbiased nature. This is emphasised by the predominate use of isolated faces over full-body illustrations to identify the other characters, which both points towards a child’s selective attention-span and also indicates the finite capacity of memory itself. Indeed, their unbounded nature allows us to see the images as fleeting recollections, emphasising the impact these chosen anecdotes have had on Algis as he has grown older – forcing the reader to look beyond the internal narrative and to acknowledge their relation to the present. Furthermore, Itagaki reserves full-page spreads for the memories that we can imagine were the most impactful as a child, such as a walk in the rain with the girl Algis secretly fancies.

Vilé’s insightful writing further helps to build up this child’s perspective. For example, the frequent use of hyperbole and misunderstanding reinforces Algis’ innocence: “There’s nothing further than Siberia… except maybe the moon!”. Plus, Algis is repeatedly echoing phrases by adults, becoming fixated with certain notions and metaphors which fuel his imagination. A by-product of the story being told through this point of view is the slow release of more tragic moments; their immediacy is diluted through the frankness and ignorance of youth, which is embodied in the delicate illustrations that accompany these moments. For example, calling their guards in Siberia ‘Bread man’ and ‘Potato man’ deflects from how violent and intimidating these men must have been. Indeed, the unknowingness and unaffectedness of both a child’s comprehension and the illustrations themselves make the painful memories catch us off guard. In fact, they become, through this dissonance, all the more poignant.

The storytelling also makes the audience ambiguous at select points, and this is made possible through the alteration of illustration and prose. For instance, when Algis is talking about poetry with his friend Veronica, a paragraph of prose declares “maybe I will read it to you some time”. Is this the child narrator Algis talking to us, the reader? Is it Algis talking out loud to Veronica? Or, is it perhaps an interruption of Vilé’s father, the actual Algis, talking to his daughter as he recounts these tales as an older man? This vagueness subsequently reminds the reader of the true nature of these memories, and their ongoing permanence for those who experienced and lived through them. Perhaps it is all three of these interpretations at once and Siberian Haiku is exemplifying the long-term effects of this exile and how memories of pain and suffering can delineate time in an all-encompassing manner.

However, it is clearly a child’s perspective which colours everything in this novel, and rightly so. It is about a child’s experience of exile, with this clash of a child’s innocence and brutal expulsion coming together to bear witness to the complete incomprehensibility of it all – being forced from your home, from your community, for nothing you have done wrong, and with no chance to protest. Siberian Haiku becomes this protestation and testifies to the wrongdoing of the past through the juxtaposition of a child’s enduring imagination and the very real suffering experienced.

Jurga Vilé (W), Lina Itagaki (A) • SelfMadeHero, £16.99/$25.99

Review by Rebecca Burke