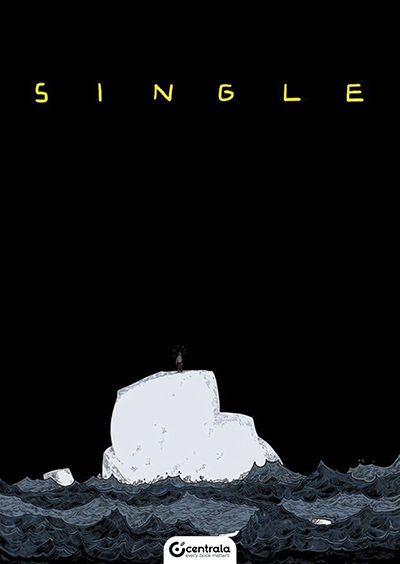

The first time we meet the unnamed main character of Jiří Franta’s Single he is a distant speck, a potentially overlooked feature of the scene, alone and stranded on top of an iceberg in the middle of an ocean. Or perhaps he’s there willingly? Defiantly isolated from the world around him? In any case, once we discover that this is not a book about one man’s survival in the arctic wilderness, the image and the book’s one-word title become a confrontational metaphor that we are challenged with unpacking.

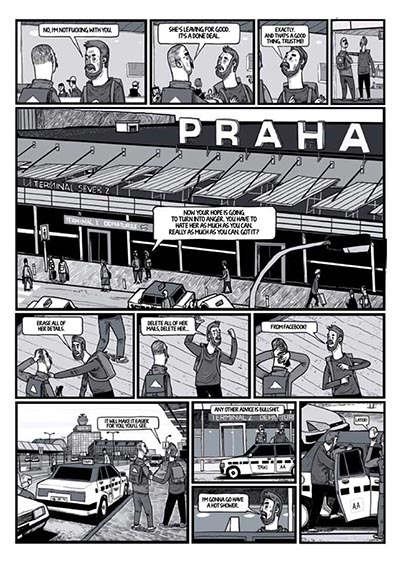

The ‘single’ of the title refers most obviously to the main character’s relationship status. Near the beginning of the story, he wakes up to a series of blunt text messages from his girlfriend, letting him know they are no longer a couple and she won’t be going with him on their planned holiday to Rome. Unfazed, or at least outwardly unfazed, he makes a call and organises for a friend to join him instead.

The ‘lads’ holiday’ conceit is a familiar one that trades on a particular set of masculine tropes, and the pop culture version of this is typically played for laughs. Think Wedding Crashers, The Inbetweeners, The Hangover: we’re meant to be in on this joke and recognise endearing, desirable, even heroic traits in these people and their single-minded pursuit of pleasure, their brash lack of regard for others, the self-destructive bludgeoning of their senses with alcohol.

But Single complicates this formula. The lads’ holiday doesn’t flow smoothly, and this isn’t just because their hedonistic plans are continually undercut by the presence of Rome’s LGBTQ+ scene.

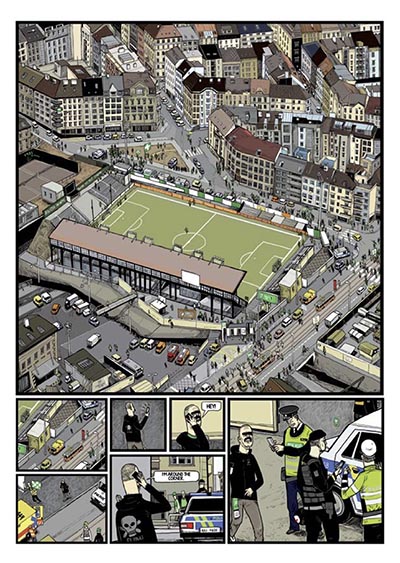

It is the way the story is told that disrupts our expectations. There is something paradoxically superficial about the first part of the book, paradoxical because it is a substantial 91 pages, filled with richly rendered depictions of the Roman urban sprawl, in all its classical and contemporary variety. But there is a lack of emotional depth and characterisation. Spoken language is often straightforwardly declarative, with words operating like blunt instruments: drinks are ordered, directions of travel are announced, a character declares confusion or anger – that sort of thing. Likewise, the design of the characters seems to operate around a fairly limited range. The main character’s face, for example, is a constant monobrowed rictus of either anger, pain or frustration, seemingly designed to generate unease. He is just a step away from collapsing into caricature or simulacra.

The page designs in part 1 also display this paradox. They typically contain busy panel layouts that fragment actions and events into finite moments, or fixate on incidental details. Chris Ware’s canonical version of this works to render pages as splendid infographics, free to be read outside of the usual temporality of a comics page; Maria Medem’s more restrained version slows down moments and causes us to pay attention to significant or beautiful lingering details. Here, the logic is initially not so clear and there’s a question over whether these are simply formal experiments.

This could of course be the case, but it’s as the book progresses into its second part that these defining aspects of the first take on a brilliantly purposeful dimension. Single is ultimately the story of the main character’s burgeoning self-reflexivity which, as well as being depicted through events in the story, is also captured in the developing nature of the storytelling itself – like a David Foster Wallace novel, the meaning is expressed in form as well as content. The superficiality of part one is therefore tied directly to the character’s psyche at that stage, with those incidental details and complex panel arrangements alluding to a consciousness that presses in at the periphery, one he’s not yet fit to acknowledge.

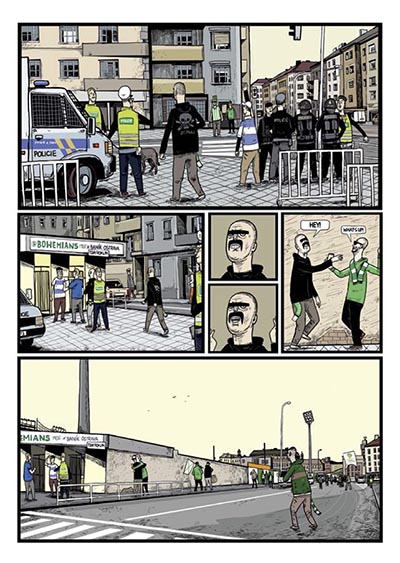

Part 2 returns the character home to Prague, where a football match early on serves as a key turning point. The crowd – all male – is charged with terrifying aggression and the threat of violence, which explodes at the final whistle. As things play out, it’s clear that the main character is no longer comfortable taking part, but he is kettled-in by police and fellow fans – he is under pressure to perform his role. His way out emerges through the one woman present at the game, a press photographer, who rescues him from a police beating and becomes a key character in the rest of the story.

It’s from this point that the stereotypes and masculine tropes evoked at the start of the book are scrutinised and deconstructed, and it’s incredibly satisfying to read the main character’s development as the events in part 2 progress. The language here becomes more psychologically revealing and panel layouts cohere more dynamically with the narrative. Dream sequences that reoccur throughout parts 1 and 2 also lend weight to this reading of the book as a tale of a slowly surfacing consciousness, and in as much as this is wrapped around a critique of constructs of masculinity, it also serves to critique the social construction of identity per se. Ultimately the book leads us back to the beginning, to a better informed re-evaluation of that man on the iceberg, his distance from anyone else, and the meaning of that word ‘single’.

Jiří Franta (W/A) • Centrala, £29.99

Review by Jon Aye