Ryan North and Albert Monteys continually twist the comic form in this undeniably self-aware adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s masterpiece Slaughterhouse-Five, for BOOM! Studios/Archaia.

Ryan North and Albert Monteys continually twist the comic form in this undeniably self-aware adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s masterpiece Slaughterhouse-Five, for BOOM! Studios/Archaia.

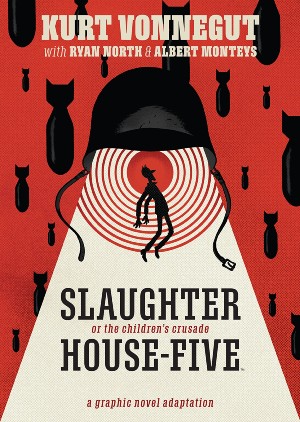

In Slaughterhouse-Five, Ryan North and Albert Monteys have taken up the challenge of translating Kurt Vonnegut’s trademark wit and existential satire into the comic medium. As with the novel, the story revolves around Billy Pilgrim’s experiences in World War II and his subsequent unsticking from time – oh, and his journey to the home planet of the Tralfamadorians who teach him that all of time is happening simultaneously and our view of linear time is a delightfully human supposition, naturally. It is clear from the outset that a main objective of this comic was to not only adapt Slaughterhouse-Five on a narrative level, but to elevate the subtext of the original by utilising the malleable nature of the comic form.

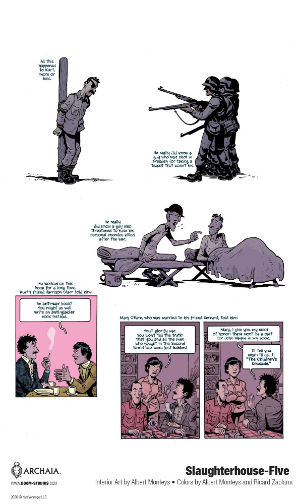

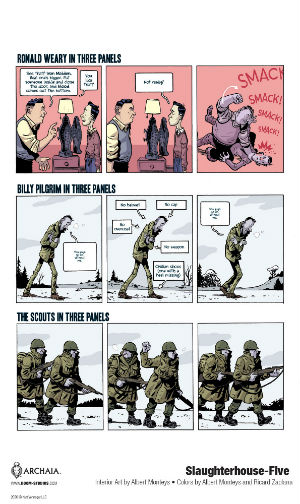

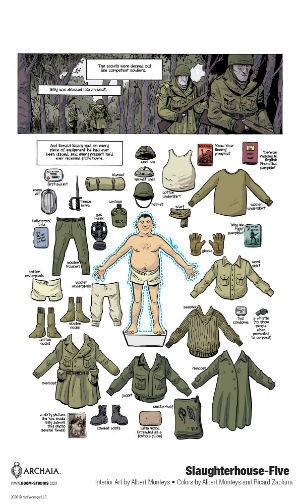

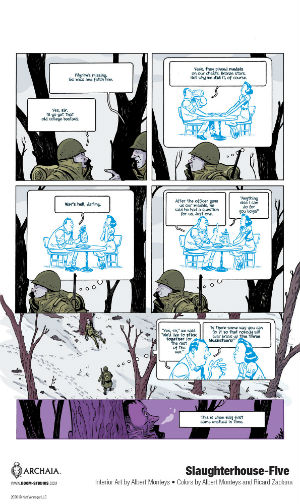

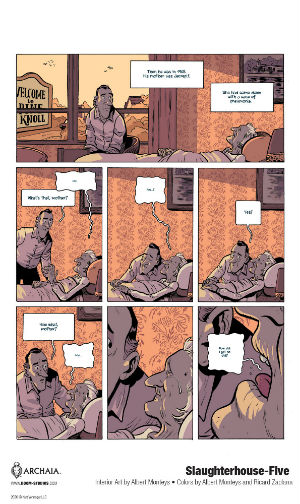

It is undeniable that North and Monteys utilise the comic form to adapt and embellish Vonnegut’s unique style, his comedic asides and spontaneous surrealism. For example, they interpret a character’s daydream sequence cleverly using panels within panels and even change the comic style entirely for some sequences: to depict comics within the comic or a retelling of events. Certain themes within the original have also been cleverly translated into the comic medium. In the novel, whenever Billy Pilgrim became ‘unstuck’ in time there were often semantic connections between the moments that the reader could infer triggered that specific episode of time travel, or, of dissociation. In the graphic novel, the same effect is established through the continuity of colours and character positioning; Billy’s gestures provide consistency across the years which can shift backwards and forwards from panel to panel.

North and Monteys do not let the comic reader forget how integrated the narrative is with Vonnegut’s own experience in the war. In fact, they even edit the opening line to make the autobiographic connection clear from the beginning: “All this happened to Kurt, more or less”. They go on to label a character in the background of a panel as ‘That’s Kurt Vonnegut’, or inform us that he was on the other end of a phone call that takes place. At times this interrupts the narrative flow that Vonnegut maintained, veering closer to a literary analysis or companion text of Slaughterhouse-Five rather than a direct retelling. Then again, perhaps this was the intention. Whereas Vonnegut led with chaos, forcing the reader to piece things together from the disjointed narrative, North and Monteys spell things out a bit more from the get-go; they even open the comic with a list of the characters within, and a visual representation of Billy Pilgrim’s timeline. The continuous meta elements make the adaptation accessible to those less familiar with Vonnegut’s work, but could appear as overkill for more discerning fans.

Overall, the Slaughterhouse-Five graphic novel adaptation is able to draw the reader’s attention to more subtle themes within the original precisely because of its use of certain comic tropes. By giving the reader a visual timeline of Billy Pilgrim upfront, it raises instant questions about determinism and free will which remain prevalent throughout. For example, in a speech Billy hears at the Lion’s club luncheon meeting, ‘no choice’ and ‘damned’ are in bold text within the speech balloons. This is standard for comics but would have looked out of place in the prose version, allowing for further layers to be influenced and reinforced. Through this simple comic addition, North and Monteys hint at predeterminism, especially as this scene comes just after Billy has said he has no control over the future.

Moreover, reading this more prominently as an autobiographical work, as North and Monteys have forced us to do, allows us to see these themes more clearly as something manifest in Vonnegut’s own ideology. It testifies to the post-traumatic stress, retrospectively diagnosed by many academics, that Vonnegut suffered with after his experience in the war and pushes the harder realities of war to the forefront. This adaptation is a good introduction to Vonnegut and is a prime example of how comics can extrapolate beyond original text-only work to reinforce pre-existing subtext and add new layers of meaning.

Kurt Vonnegut & Ryan North (W), Albert Monteys (A), Scott Newman/Albert Monteys (CA) • BOOM! Studios/Archaia, $24.99

Review by Rebecca Burke

[…] • Rebecca Burke reviews the metatextual overkill of Ryan North and Albert Monteys’ adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five. […]