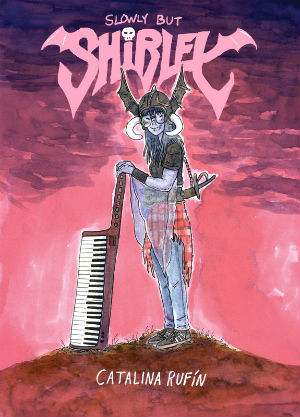

With Young Adult fiction there is always the question of who exactly the intended audience is. Are stories of teenagers growing into adulthood meant to serve as a guide for young people undergoing that transition or can they capture something more universal about our continual growth and change as human beings? Slowly But Shirley by Catalina Rufín is a graphic novel that is ostensibly about the titular teenaged, bespectacled, bat-eared protagonist coming into her own through the power of heavy metal music. But it is also a story that so nails the deeper experience of finding yourself and the community you belong to that it speaks to readers of all ages.

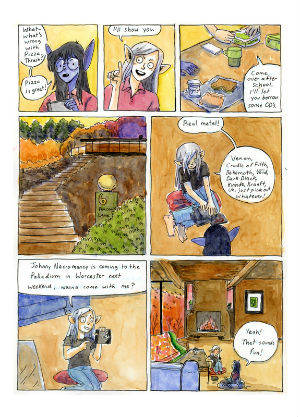

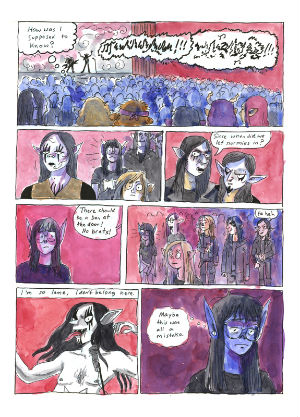

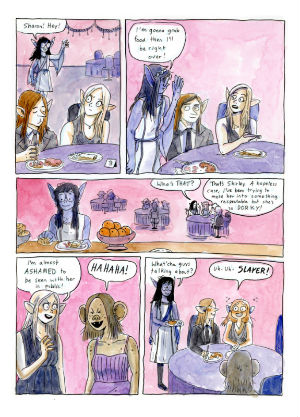

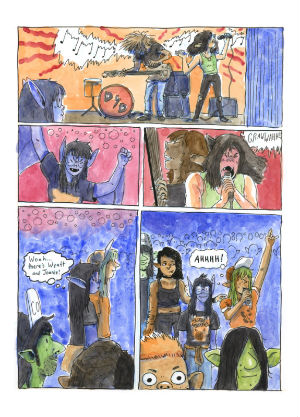

Aesthetically, the softly watercolored world of Slowly But Shirley is Rufín’s love letter to a collective mix CD era of being a teenager. One where you spend an afternoon sitting cross-legged on the floor listening to music with a friend. Where freedom is riding the train to see a concert without worrying about getting home in time for curfew. There is a nostalgic fuzziness to the colors and loosely sketched backgrounds that always captures the atmosphere if not the specifics of the moment. The inviting humility of Rufín’s human-animal hybrid character designs grounds their performances in the everyday struggles being depicted. When this physical performance is combined with the often comedic hyper malleable cartooning on the characters’ faces, Rufín gets at the ecstatic truth of the joy and sadness Shirley will experience on her journey to her place in the world.

Aesthetically, the softly watercolored world of Slowly But Shirley is Rufín’s love letter to a collective mix CD era of being a teenager. One where you spend an afternoon sitting cross-legged on the floor listening to music with a friend. Where freedom is riding the train to see a concert without worrying about getting home in time for curfew. There is a nostalgic fuzziness to the colors and loosely sketched backgrounds that always captures the atmosphere if not the specifics of the moment. The inviting humility of Rufín’s human-animal hybrid character designs grounds their performances in the everyday struggles being depicted. When this physical performance is combined with the often comedic hyper malleable cartooning on the characters’ faces, Rufín gets at the ecstatic truth of the joy and sadness Shirley will experience on her journey to her place in the world.

The reader follows Shirley over the course of several months of her second year of high school as she immerses herself deeper into her local music scene via her fandom of the indie metal band Death Dealers. Her joyously raucous experiences of seeing live music contrasted with her feeling like an outcast at the all-girls Howard Academy. Where time and again we see Shirley put up with the manipulations of her catty disingenuous pseudo best friend Sharon rather than face the embarrassment of having to eat alone during lunchtime. In Shirley the reader recognizes the myriad small ways in which we sacrifice our self-esteem in order to get along; a vulnerability that is at its most acute when you are young, but one that never fully goes away.

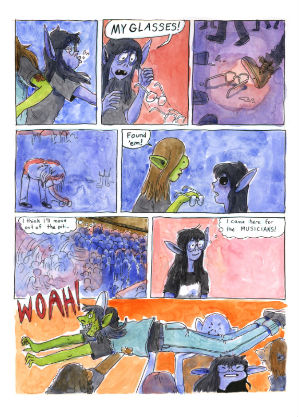

Rufín nicely captures this experience of identity-building clashing with the need to fit in through the way that the minor genre separation between Sharon’s preference for Black Metal and Shirley’s love of Pizza Trash is enough to create friction between the two. Hoping to not be seen as the kind of dork that she will be called behind her back regardless, Shirley agrees to go with Sharon to a Black Metal concert. The vaulted stage, the rigid rules of behavior at a Black Metal show espoused by Sharon, and the snarky commentary from the audience once again contrasted with the exuberant energy seen previously at the more rag-tag Death Dealers concert. The unwelcoming nature of even this adjacent community capped by Shirley getting covered in pig’s blood à la Carrie, and Sharon berating her as a sheltered baby for being upset by it.

In her journey to acceptance, Shirley will try on more than just a borrowed Black Metal t-shirt. We see her put on a more feminine persona to attend the winter social in hopes of realizing her secret crush and dancing with Sharon, only to be ignored in favor of a slow dance with a goony boy. Feeling herself becoming further isolated by her pseudo friends at school gaining boyfriends, Shirley then throws herself into her piano studies. Once again donning more feminine garb for the recital at her church, her performance is met with applause but it is far from the community she is seeking. Any self confidence that Shirley has after the recital instantly washed away when she logs into social media and sees that Sharon having a blast at the Power Metal festival she chose to forgo in favor of the recital.

Finding no home in the staid world of classical music or the stratified Death Metal scene, thankfully Shirley finds her place amid the crowd at a Death Dealers show. She realizes that the band she loves are just as dorky as she is. When her glasses get knocked off in the mosh pit, an audience member picks them up and hands them back to her rather than stepping on them. Most importantly she finds a role model in Death Dealer’s keyboardist Joanie. In their shared instrument Shirley can project her idealized future self onto the fiercely proud Joanie. When Shirley breaks down in tears at the sight of Joanie up onstage singing about how she doesn’t need friends or a boyfriend to love herself it is a powerful reminder of the way in which music and art’s true purpose is to help people feel less alone in the world.

Slowly But Shirley comes to a somewhat abrupt but happy conclusion. Shirley starts to make choices that bring her towards true friendship and true acceptance. She overcomes her challenges by being her authentic self, but never in a way that feels like an after school special. Within her chosen community she is celebrated and encouraged for who she is not who she pretends to be to please others. With every thin squiggly line and visible watercolor brush stroke Rufín perfectly captures the struggle to and joy of realizing this deeply human desire in a way that grabs the hearts of the reader. It is impossible not to see yourself in Shirley and all her awkward bravery and want only the best for her.

Catalina Rufín (W/A) • Self-published, $20.00

Review by Robin Enrico