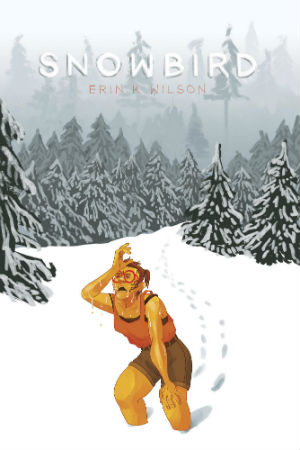

As they get older everyone has to reconcile who they once were with who they have become. For the autobiographical cartoonist this is even more complicated as they also have a version of their past self that is immortalized in the pages of their work. While Erin K Wilson’s Snowbird begins as a retelling of a pivotal time in their early 20s from the perspective of their late 20s, it is the book’s coda written in Wilson’s 30s that makes the work transcendent. In reflecting back on not only the events depicted but their choices as an artist in making the earlier part of Snowbird, Wilson transforms a too self-serious memoir into a larger meta commentary on the pitfalls of trying to write about the larger world when you’ve barely gotten a handle on your own life.

As they get older everyone has to reconcile who they once were with who they have become. For the autobiographical cartoonist this is even more complicated as they also have a version of their past self that is immortalized in the pages of their work. While Erin K Wilson’s Snowbird begins as a retelling of a pivotal time in their early 20s from the perspective of their late 20s, it is the book’s coda written in Wilson’s 30s that makes the work transcendent. In reflecting back on not only the events depicted but their choices as an artist in making the earlier part of Snowbird, Wilson transforms a too self-serious memoir into a larger meta commentary on the pitfalls of trying to write about the larger world when you’ve barely gotten a handle on your own life.

Snowbird is a book that is greater than the sum of its parts. The bulk of the book consisting of the first part of what Wilson had planned to be a longer work and a shorter coda written and draw five years after the fact, wherein the 32-year-old Wilson has to explain to their 27-year-old self why they didn’t finish the book. Though not the originally intended version of Snowbird, this metatextual version is itself a complete whole. Wilson does what few if any autobiographical cartoonists have done and confronts not only their previous self but also the way in which they presented that past self in their work. Wilson finds their younger self as incomplete as their unfinished graphic novel but effectively gets ahead of any potential critique of the work by pointing out its flaws more cuttingly than even the harshest critic, and with the insight that only a work’s creator can give.

Which is not to say that the first section of Snowbird is a failure. Wilson’s artwork is animated and emotive with a style that is reminiscent of Blankets-era Craig Thompson. In using that expressionistic style they do a marvelous job of capturing the whirlwind of emotions that they were going though in their early 20s. It’s a smart aesthetic choice as, more than anything, the first portion of the book is about the tumultuous experience of being young and trying to find your place in the world. Like the titular snowbird Erin is unable to stay in anyone place for to long, though the main portion of the book finds them grounded in New Orleans during the winter of 2010; a setting they capture equally well in their often ornately detailed background drawings. The character’s performance, the panels’ composition, the story’s pacing… all are strong and confidently and effortlessly executed in the service of telling the story they were trying to tell.

The issue with the first part of Snowbird then is not how Wilson captures objects in lens of their metaphoric camera, but more what they trains that lens on. The coda directly addresses the self-centered nature of the first portion of the book, which is a fair critique but one that scratches at a deeper issue. Wilson was certainly not the only cartoonist to try and tackle larger themes from a personal perspective, particularly at the time the bulk of the book was made. The way in which they present the personal side of the story is also in much the same manner as wide swaths of cartoonists have presented the experience of being in your early 20s. Young artists will forever tell stories where having their heart was broken is a monumental catastrophe. They will always burn with a desire to tell you how loved they are by their cool creative friends and how great their house parties are; how crummy their low paying jobs are or how going to a show and hearing a song that catches you right in the feels is a transcendent magical experience. Wilson did all of these and they are the least of their artistic sins. They made the art that you make when you are young.

Likely because of Erin’s age at the time of the story and Wilson’s age at the time of the retelling, both consciously and subconsciously the first part of Snowbird is about their desire to be loved. On the surface there is the plotline of the ex-boyfriend who has broken Erin’s heart, leaving them clamoring for affection and validation, but on a meta level there is also the Wilson who desperately wants the reader to love and validate them. So much so that in the coda the reader likely sides with older Wilson calling out the younger Wilson who felt the need to tell the reader all about Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Of The United States. Sadly the Wilson who wrote the first portion of Snowbird seems to have suffered from the all too common anxiety that young people have of being seen as an altruistic and aware person. This need to present oneself as being worthy is further exemplified by the scene that the younger Wilson included of their experience at the coffee shop assisting a customer who is recovering from a stroke. Like the foreshadowed by, never drawn portion of the story surrounding an acquaintance’s violent death, the younger Wilson was using someone else’s tragedy to flavor their own life story. Yet when the older Wilson chastises their younger incarnation for these trespasses it is done with pity. They realize that their younger self like so many of us had little self-awareness of how lost and desperate for validation we were when we were less fully formed.

Where things become thornier are the parts where Wilson tries to address larger social issues within the framework of their autobiography. The reader easily agrees with the older Wilson when they critique their younger self for the unfocused nature of the first part of the book. As was the style at the time, Erin didactically speaks directly to the reader about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the gentrification of New Orleans, and warehouse artist collective The Ark. As the older Wilson points out, the issue is that not only are these complex topics are given short shrift but that they are haphazardly juxtaposed with intimate details of Erin’s romantic life. When the younger Wilson responds with the conviction that they could encompass all these topics under the umbrella of their own experience it reveals their well meaning if misguided youthful hubris. When the coda touches on the fact that the initial portion of Snowbird was funded through Kickstarter it is another subtle reminder of the limits of the can-do attitude of the early 2010s era in which it was made.

Still, the most damning criticism the older Wilson has for their younger self is one that the reader never could have guessed without it exposed in the coda. In their dialogue it comes out that the younger Wilson had consciously whitened both the owner of the coffee shop they were working at as well as the coffee shop itself. Even worse is that the younger Wilson had asked the permission of all the people featured in the first part of Snowbird save the coffee shop owner to be in their book. While these past artistic decisions undermine the social justice persona of the younger Wilson it also speaks to the major differences between their older and younger incarnations. This willingness to change the details of the narrative to suit their telling of the story goes hand in hand with younger Wilson making themselves the center of it. When you are young its hard to see far outside of your own story to see that other peoples stories are just as valid, and beyond that the fact that life doesn’t always work the way it does in stories.

The coda serves as commentary on the first section but also gives it resolution even if it’s not the one the younger Wilson wanted. The book didn’t get complete in the way they planned, the cool arts collective warehouse is now condos, the potential love interest doesn’t pan out, and the avant-garde parade has lost its original meaning by becoming too popular. The older Wilson is also burnt out on activism, but has gained the self-awareness to realize that not only were they trying to take over every group they joined, but that activist groups might be better lead by people of color than another idealistic young white person. Much to the chagrin of the younger Wilson their older counterpart has also had to sincerely grapple with their mental illness. The suicide pact that Erin makes with her phantom-self in the first portion is staved off not by finding the validation they are so desperately seeking, but by having the humility to seek professional help. This is no storybook ending, but neither is it an ending. In the final pages the elder Wilson returns home to confront their current phantom double who poses the hopeful question of what they will make next.

Snowbird does so much more than solve the problem of an unfinished memoir. In earnestly confronting itself the book become a way in which to question how artists retell the story of their lives. What gets highlighted? What gets left out? Can we properly tell other people’s story within ours? How far removed do we need to be to even tell our own story? Though Wilson doesn’t provide concrete answers, the act of probing these issues in such a tangible way is revolutionary. Just as Wilson need to ask themselves these questions to grow as a person, so to do all autobiographical cartoonists need to ask them of themselves if the form is to grow.

Erin K Wilson (W/A) • Silver Sprocket, $20.00

Review by Robin Enrico