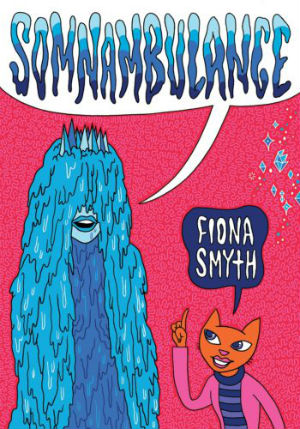

Koyama Press’s release of Somnambulance by Fiona Smyth performs a tremendous service to comics readers by collecting a substantial volume of Smyth’s work within the medium. The book is valuable in terms of preservation with the bulk of the work collected having been out of print since the ’90s or in some cases never published at all. In this regard Somnambulance rightfully restores Smyth’s place within the collective history of indie comics. What is also striking how much her comics are a window into the time in which they were made, but also how they presage ideas that would take another two decades to fully take hold. The work is highly charged with spirituality and sexuality, frequently transgressive (particularly for the era) in both subject matter and design. While the strong feminist core behind these decisions gives the work a timeless quality that feels as vital today as it must have in its time.

Koyama Press’s release of Somnambulance by Fiona Smyth performs a tremendous service to comics readers by collecting a substantial volume of Smyth’s work within the medium. The book is valuable in terms of preservation with the bulk of the work collected having been out of print since the ’90s or in some cases never published at all. In this regard Somnambulance rightfully restores Smyth’s place within the collective history of indie comics. What is also striking how much her comics are a window into the time in which they were made, but also how they presage ideas that would take another two decades to fully take hold. The work is highly charged with spirituality and sexuality, frequently transgressive (particularly for the era) in both subject matter and design. While the strong feminist core behind these decisions gives the work a timeless quality that feels as vital today as it must have in its time.

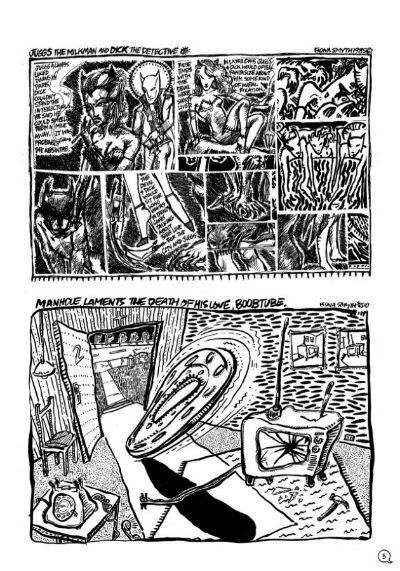

In seeking to be an omnibus of Smyth’s comics, Somnambulance contains several short pieces from the mid to late ’80s. These are the weakest of the collection as Smyth is clearly figuring out her style and her voice, but they are revelatory in showing how quickly she comes to the aesthetics that will define her work in the ’90s. Scratchy cramped panels give way to the larger though equally dense panels or splash pages. From the beginning Smyth’s design sense focuses on filling the panel with lines, with her prevailing style being large abstract patterns that are often brushed into the background, surrounding the characters with a nervous squiggly energy that recalls Keith Haring’s work. Other artistic choices surface early on such as Smyth’s habit of adding an almost quilted pattern around the outside of panels as well as her preference for narration over dialogue to drive the story. While she experiments with various characters in these early works, only Gert the Mannequin carries forward into later stories.

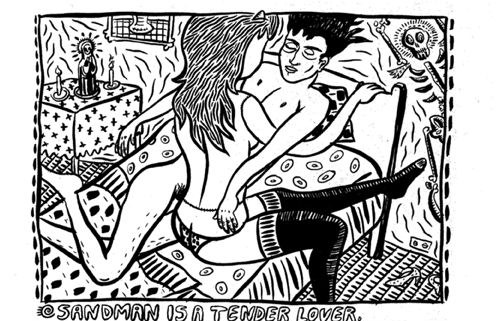

It is with Gert that Smyth finds her voice as an artist. From the first Gert story we see Smyth seeking to use the transgression of taboos as a means to discuss female desire. Gert tries to get work as a stripper but is fired because of her emotionless mannequin face, instead finding better employment at as the popcorn girl of an X-rated movie theater where she loves to watch the movies. In becoming fascinated with sex Gert becomes a hooker who is particularly popular with necrophiliacs due to her rigid waxen body. All of this is played for comedy, but it casts Gert as a woman trying to claim her sexual agency. This becomes even clearer in the second Gert story where she has found the perfect partner in the form of the narcoleptic Sandman. In his drowsy state Gert can aim all of her burning desire at him without fear of being rebuffed.

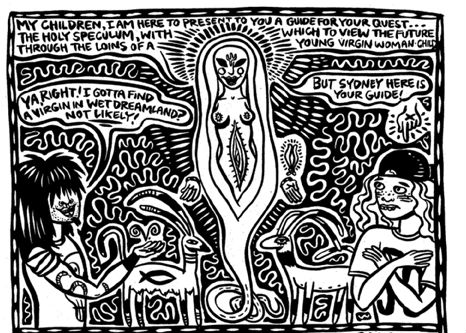

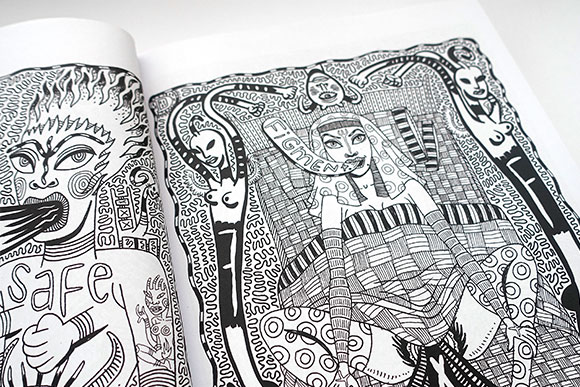

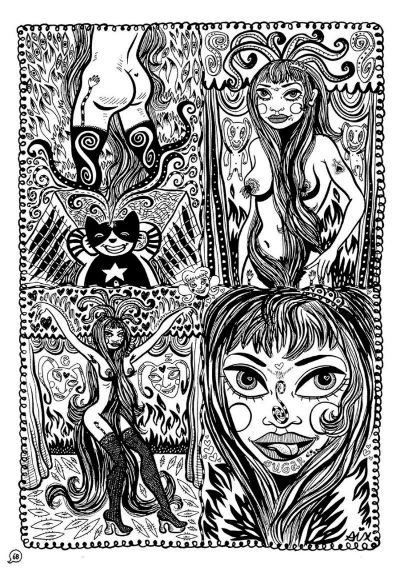

Though Gert continues her lusty role as a one of the central characters in the issues of Smyth’s Nocturnal Emissions, she is only part of the pervasive female gaze at work this collection. In a way that feels both anachronistic and of the now, Smyth’s comics are intensely yonic. One of her central visual motifs is the similarity between the shape of the eye and the shape of the vagina. Both are repeated frequently throughout in both backgrounds and adorning characters’ bodies. Smyth draw her women as lustful, at times barely clothed, with wild unkempt hair in a way that evokes the more primal and pagan femininity associated with (especially modern) Feminist Witch culture. Equally aesthetically of the ’90s and today are her tribal intersex alien/angel figures, or her Keane painting eyed Virgin Mary. What is unique her is that by using such specifically female coded and now forgotten pop culture iconography as Keane paintings and Troll Dolls, Smyth conjures a direct portal to an experience of the ’90s that has been lost in the intervening years. Comics has an abundance of representations of the male weirdo artist from the ’90s, without this collection we would have almost none of the female counterpart.

Also of its time is narrative structure Smyth employs in the issues of Nocturnal Emissions that make up the middle of Somnambulance; at first seeming like multiple unconnected vignettes akin to the loose anthology nature of Clowes’ Eightball. Only over the course of the series’ five issues do the stories of Gert the Mannequin unsuccessfully trying tying to escape her lusty past in a Nevada nunnery, Toad the metal-head’s trip into the Land of Wet Dreams, and the interpersonal drama of drug buddies Roach and Pussy start to interweave. The narrative is then up ended by the meta-revelation that all the protagonists spring from the imagination of Mia a teenaged girl perhaps standing in for Smyth as the creator. That this final revelation comes from an unpublished 1993 issue of the series makes this collection a minor miracle. Even more so is that the entire story had no satisfying conclusion until Smyth wrote and drew one in her modern style for this book. Fittingly it shows the protagonists in the modern day reflecting back on their wild younger lives.

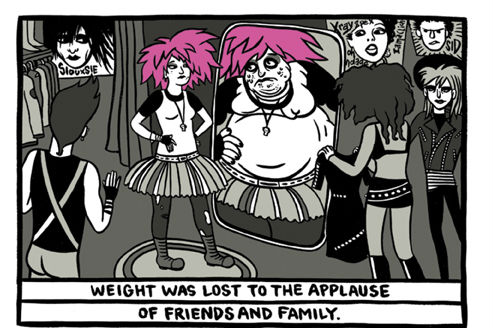

The slicker computer colored style Smyth uses in the coda to Nocturnal Emissions can also be seen in another recent autobiographical strip called Plus Punk Rock Rebellion recounting her experience with negative body image. The strip serves as a companion to a few earlier comics about body image, but also provides an interesting commentary on the Smyth’s earlier work. In one panel she depicts herself painting her feminist imagery from her ’90s comics while admitting that at the time she was afraid to call herself one. It reframes the transgressive nature of her ’90s work as a gut level reaction against the culture of the time. While her comics mixing religious imagery mixed with sexuality might almost seem old hat now, at the time one can imagine them being deeply liberating for Smyth. Even today her comics depicting her sexual fantasies or boring life as a freelance artist feel rebellious. Depictions of young women living independent lives were hardly mainstream at the time, have rarely been preserved, and have only become a more prevalent narrative in comics in the last decade. In reprinting work that would otherwise be lost to the ages Somnambulance is a strong reminder of both the context in which female indie cartoonists worked at the end of the 20th century and also of how that history connects to the work of modern cartoonists.

We can even track this evolution in to the present as some of Smyth’s mid-2000s work is also included, showing her gradual shift away from her ’90s aesthetic. Her busy black and white line work remains, but the imagery moves from the spiritual realm into the natural one. Though it is an oozing and corrupted natural world filled with mutated malformed creatures where figures are bent at violent angles or bleeding with mountains jutting out from under the skin. Gone are the eyes and vagina imagery replaced by geodesic spider webs. This more aggressive and violent tone is best reflected in an unpublished comic from 2006 where Smyth recounts her frequent nightmares rather than letting us in on her sexual dreams. Whether this shift can be attributed to developments within world history or within Smyth’s own life is left unanswered, but whereas before there was humor to be had in some of the more grim situations she depicted now the illustrations feel far more urgent. This continues into a few short recent comics where images and text are combined poetically with no direct narrative yet still remain evocative through Smyth’s ability to weave her lettering into the grotesque nightmare-scapes she renders.

There is something profound to seeing an artist evolve over the course of thirty years, especially one whose work has so long been out of the public eye. With Somnambulance Smyth goes from relative obscurity to firmly within the indie comics canon. Those who had previously seen only small selections of her work in passing now have an appropriate tome to pore over. While readers who have never seen her work a granted the boon of discovering a fully formed cartoonist with a large body of work. Fascinating historically, vital thematically, gripping artistically, on all levels Somnambulance is a necessary and deeply rewarding read.

Fiona Smyth (W/A) • Koyama Press, $29.95

Review by Robin Enrico

[…] Robin Enrico reviews SOMNAMBULANCE by Fiona Smyth, writing “Fascinating historically, vital thematically, gripping artistically, […]

[…] Read the whole review here! […]