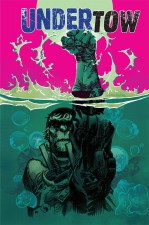

As the third issue of Undertow hits the stands from Image Comics, Broken Frontier talks to its writer – Steve Orlando. In the first half of a two-part interview, we chat about hope, liberty and monster crustaceans.

I jumped at the chance to interview Steve Orlando about his oceanic odyssey. Undertow has gotten under my skin. From its debut it was clear that this was no ordinary story – ambitious, huge in scope and too big for a single issue of any comic. And so it has proved. The second issue had massive strength, before #3 hit readers with a big reveal and mounting tension that will keep you baying for more.

So, given the power of the subject, this interview was always going to be interesting. However, it also proved to be a lot of fun, as Steve Orlando demonstrated his passion for his craft and indulged the ignorance of his novice interviewer.

Hi Steve. The pre-publication opinion on Undertow seemed to be that you and Artyom Trakhanov were going to offer us a pulp-monster affair. But it has confounded my expectations; I really don’t know where it is going and what it is about – IN A GOOD WAY. So, first of all, could you explain to me what Undertow is about?

Hi Steve. The pre-publication opinion on Undertow seemed to be that you and Artyom Trakhanov were going to offer us a pulp-monster affair. But it has confounded my expectations; I really don’t know where it is going and what it is about – IN A GOOD WAY. So, first of all, could you explain to me what Undertow is about?

Well, we’ve got pulp monsters! Did you see the giant mantis shrimp in #2, by chance? But you’re right, we’ve got more than that too. Undertow is, at its core, about our relationships with home and, by extension, freedom. Now you might say, “Steve, come on, that sounds like a Lifetime movie”. Sure, but ours has lasers and fish people, and that’s where the pulp monsters come in.

But those exploding crab scenes need to have a soul. And the soul is two men wrestling with their home – in this case, Atlantis. Both have so much anger, but how do they react to it? For Anshargal, it is detachment. He hates Atlantis, but simply wants to live away from it. Living well is the best revenge, that is.

For Ukinnu, though, his is a younger anger, more petulant, and he wants to hurt Atlantis – to get back at it, for grinding him through its social soul-crushing machine. That’s the two generations of rebellion coming together; Anshargal is the seasoned social activist, who has been around the block and knows the dangers of unchecked rage. Ukinnu is the young upstart who idolises him but maybe thinks he’s getting old.

I think this is a universal thing: find me someone that doesn’t have a complex relationship with their family, with their hometown. And think of how that anger or discontent, big or small, changes through the decades of life. What does it mean if the finger was on your trigger at one time, and what if another?

And with the need to get away comes the even purer heart of the book – the meaning of freedom. Anshargal is an idealist. He wants people to have a place to live how they want, unchallenged by society. But everyone’s wants may not align. And, more so, freedom does not mean safety.

Often we have to give up security for freedom, and that is what we do in this story by aligning our characters with the American Western pioneers of a century ago. Or the pilgrims coming to the American continent, or modern-day citizens living on the outskirts where no one bothers them.

They give up safety, they give up luxury, for the chance to live free of expectations. The frontier is raw, it is undiscovered and it is dangerous. But to unchain ourselves from society, we have to go where it will not go. We have to make home where it will not sustain itself. And the characters of Undertow are realising that there is a cost to their freedom.

I keep recalling pioneers or explorers, living rough on the very edge of the discovered world. They must have had wonder in their eyes, but the primal lands they sought could also have killed them at any moment. Nature was always a second away.

What I have liked most about Undertow so far is that it doesn’t seem to offer much in the way of hope. Anshargal’s group is characterised by infighting, the dream of living on the surface likewise. You present readers with a much more realistic portrayal of the search for utopia. Where does that come from – political reading? History? Literature? Because it flies in the face of most current popular culture, which is beset by shiny promised lands.

I think that you’re right. Idealism is nice but is often bungled by that pesky human nature. We do like to think that these utopias work out, in the way we like to think that if we could have a house in the middle of nowhere we’d be safe and could do what we want.

Just like the expectation of freedom, the expectation of the Deliverer’s society does not match the reality. It can’t. Because as soon as you have two people in a room, they’re bound to disagree on something, even if they both want the same thing, because they don’t define the same thing the same way. And that comes from politics, it comes from relationships.

Look at how many myriad definitions there are of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” and what it entails here in America. You have people on one side asking for rights and invoking it, and others restricting those rights by using the same justification. The big truth about utopia is that it’s fiction, because we cannot seem to give up the obsession with ourselves as a global culture. And if utopia is going to work, we have to be willing to work as a team.

But life rarely ends up being a team sport, and with the advent of YouTube and Instagram and apps we’re fetishising ourselves even more. We’re the stars of our own everyday lives, which is great for our self-esteem, but not so good for a situation that involves compromise. History is full of plans with good intentions for the world that didn’t work out.

But having said that, I’m not sure if the book is lacking in hope. Maybe lacking in hope for a perfect world, but there’s no such thing. I think there’s hope for it to work out, maybe, but the citizens right now don’t know what that means. But if they can’t adjust themselves, if they can’t stop putting themselves first, then maybe it won’t. But if that’s how they’re acting, have they really left Atlantean ways behind?

Why is Anshargal so keen on living on the surface? It doesn’t seem very nice there. Is it merely an escape from an oppressive regime? Or does he want to turn back the evolutionary clock – ie, to live like the humans?

I think it makes sense if, like we talked about above, you think of pioneers. You’re absolutely right. It is not always very nice there. But sometimes that’s where you have to go if you want a chance to do what you want and live as you want.

For Anshargal, his experience in Atlantis was so traumatic that he needed a clean break, something so unlike his old life that he could tuck those memories away and put them in the attic. For someone like Bau Zikia, who is his intellectual counterpart, she has a chance to study humans and study Atlanteans at the same time. She is a sociologist at heart, and wants to learn from humans and to teach Atlanteans, as well as to challenge social conceptions.

And that’s the thing: Atlantis has an oppressive regime, but not in the way that we expect. We visit the cities in brief snippets and people live well. But they don’t know they’re being controlled by the media, by marketing, by corporations.

And that’s the thing: Atlantis has an oppressive regime, but not in the way that we expect. We visit the cities in brief snippets and people live well. But they don’t know they’re being controlled by the media, by marketing, by corporations.

They’re kept fat and happy, and their lives are uneventful. And those that fall through the cracks are quickly forgotten, or depicted as having not worked hard enough or failing to support the economy with menial jobs.

Maybe some would look at Atlantean life and not see anything that bad there, and that is an interesting statement to make. It’s only bad if you want to think for yourself, not be led by the wrist by a CEO or a lobbyist or a councilperson.

Anshargal was spat out of the machine; his whole life and family were just corporate waste. So just like pilgrims coming to America to escape the church, he has come to the untamed wild to start anew. He knows it’s unsafe, and that’s why he’s made himself into the protector of his people.

He is basically giving up even his second life – the personal part of it, at least – to ensure that no one else on the ship has to worry about danger. It’s actually like the conversation between the Operative and Mal in Serenity, when the Operative says that while “they’re making a better world”, it’s not one that he’s going to live in.

Anshargal is laying the foundation, he’s clearing the jackals from the property, because he sees the surface as a place that could free future generations. And that’s why he’s risking his life to find the Amphibian – so that future generations, not his, could perhaps exceed his boundaries and live unchecked on land.

This is really the heart of his mission; he’s just like a parent, but for a family of thousands. And every parent, every generation, hopes that the next will do better and achieve more than the last.

In the second part of our interview, Steve tells us about keeping readers on their toes, the influence of Russian literature, his journey in the comics industry and the one secret that Redum Anshargal wouldn’t want anyone to know…