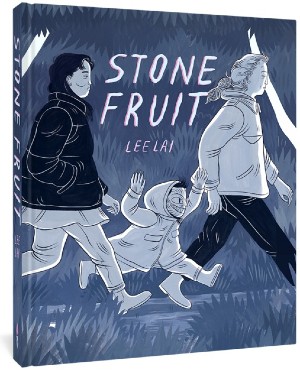

Lee Lai’s debut graphic novel Stone Fruit is a tender and self-aware story with relationships at its heart: queer relationships, sibling relationships, parental relationships, and the self-referential relationships of our past and our communities.

Lee Lai’s debut graphic novel Stone Fruit is a tender and self-aware story with relationships at its heart: queer relationships, sibling relationships, parental relationships, and the self-referential relationships of our past and our communities.

Bron and Ray are at their ‘best’ when Nessie was six, our narrator tells us. Nessie is Ray’s niece, and the couple look after her a few times a week to let Amanda, Nessie’s mum and Ray’s sister, get on with work. The illustrations of the opening sequence depict this ‘best’ time and show the trio playing amongst nature together; their bodies are unbounded by the panel borders as we see the scene traverse these lines with ease. This technique emphasises how the characters feel limitless, primitive, and perhaps even monstrous in comparison to the societal norms of those who may happen to observe; in other words, they are liberated. It is only when expectations intrude on the scene – Ray’s sister Amanda calls her to ask them to bring Nessie home – that these primitive forms begin to fade and the illustrations return to more familiar humanoid forms, contained once more within their respective panel borders.

Indeed, in Stone Fruit, Lee Lai repeatedly shows us the impact and detriment of expectations. Expectations may, in fact, be posed as the antithesis to the smooth and care-free relationship ideal, or the relationship presented to us back in that opening scene – an apparent unity of souls, free and flexible and unstoppable. What stops this, what grinds this adventure and play and euphoria to a halt, is the arrival of expectations; the phone call from Amanda expecting something to have gone wrong, expecting them to return at a certain time, expecting Bron to be a bad influence, and so on. These various expectations intrude on the scene and return our characters to reality.

Moments of dialogue routinely drain a scene of the usual gouache tones of Lee Lai’s colouring style, emphasising certain phrases and their importance to characters by paring the illustration back to the line art. Again, these moments often occur when expectations do not align with, or bring characters back to, reality. For example, when Amanda seeks closeness with Nessie and is rejected and, in another scene, when Amanda and Ray argue together: “You’re always rushing to assume the worst of me, you know that?”. These expectations, for closeness, accountability, gender identity, etc, shape the dynamic of the various relationships presented in Stone Fruit. Amanda expects family to always ‘show up’ and to be hard work, Ray expects romantic love to involve being looked after and cared for, whereas Bron is struggling with the religious expectation of her family and upbringing, as well as those of Ray: “I got sick of feeling guilty and hopeless […]”.

Ultimately, when Amanda tells Ray “I think it’s foolish to put all your belonging into any one person” – which is one of many of Lee Lai’s heartbreakingly beautiful pieces of dialogue – this exemplifies the core of Stone Fruit; placing too much of your belonging in another is expecting too much of them from the get-go. It is when we start to loosen these expectations, to enjoy the chase of living in the moment, chasing the elusive silver dog amongst the trees, that we are fully liberated and can flourish in our relationships with each other: seeing each other as we truly are. Lee Lai shows us the difficulty of doing this in actuality, but also hints at the exceptional relationships we can nurture when we give each other the freedom we deserve.

Lee Lai (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books, $24.99

Review by Rebecca Burke