For someone that has experienced a psychological trauma, the natural impulse is to seek out a safe space and take refuge. But the problem never goes away, it simply stays there, and can grow into a monster that eventually dominates their life and debilitates their daily functioning. Recovery instead involves a gradual process of confrontation and understanding, slowly, one step at a time, in small, manageable chunks. The trauma, the fear, the anxiety never goes away, but the person grows a part of their character that is braver and stronger, a part that takes control when they are faced with the same situation.

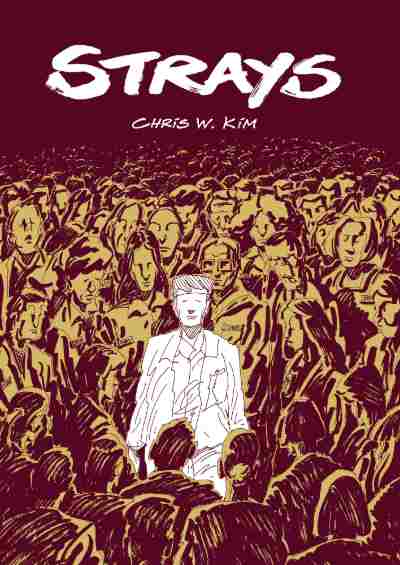

The main character in Chris W. Kim’s Strays is a man recovering from some kind of trauma, an event that has produced a rupture in his past life, causing him to uproot and move to find his sister in another, unnamed city. It’s not clear what the event was: the explanation he gives his sister, Casey, is deliberately obscured, suffocated by overlapping speech bubbles and falling out of panel. But the book’s prologue shows us silent glimpses of an incident on a construction site – a mistake? – where out-of-control machinery gouges a hole in the ground, structures collapse and an entire town is swallowed up in an immense sinkhole. The imagery is very direct: the ground has fallen out from beneath the character’s feet, his world has collapsed around him, and he must construct it anew.

Work is an important, resurfacing theme in the book, tied to notions of competence, self-efficacy and self-worth. We often see people at work and, through the tasks they perform, embedded within the fabric and rhythms of the city. Casey lives alone in a tower block and works from home, an undescribed job that seems to involve editing websites, videos or sound. She allows her brother to stay and eventually encourages him to find work. When he finds a role as a delivery truck driver, it seems a sense of self starts to return. He becomes hopeful, thinks about the future, starts to plan holidays. Casey urges him to slow down – one step at a time.

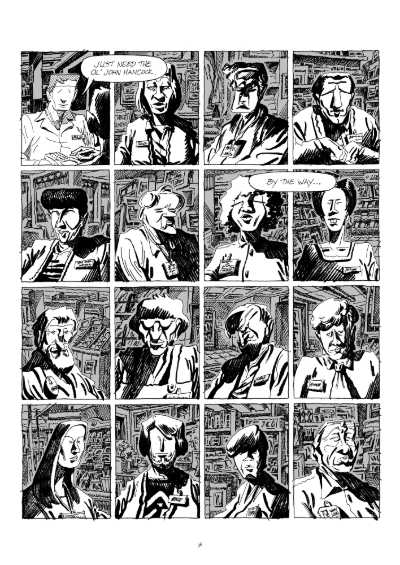

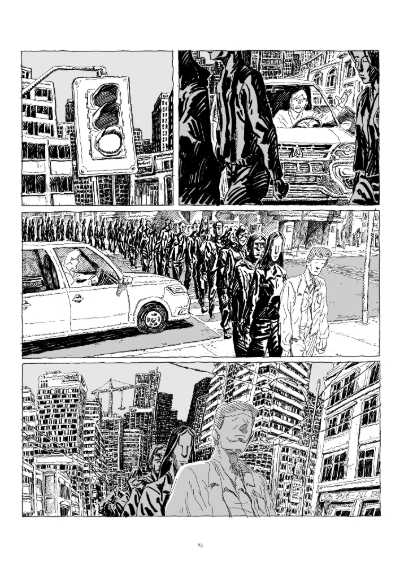

But the trauma is still there, and its effects start to seep back in. As Kim’s protagonist goes about his delivery route, he gradually encounters people he recognises, figures from his past that seem to have also relocated to this city after the destructive event. He is happy to see them at first, trying to engage them in conversation, sending them messages about meeting up. But these strange, distorted and uncanny figures never respond, they don’t talk or reply, they simply appear and stare and grow in number.

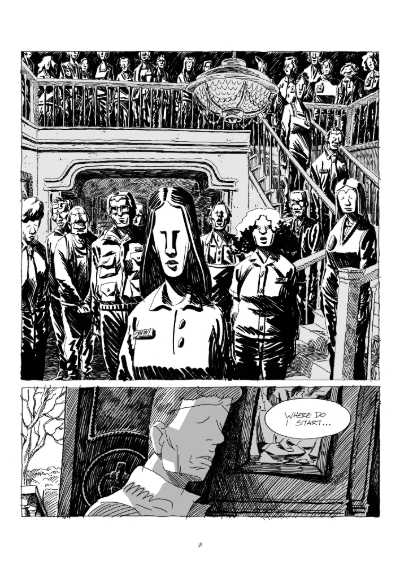

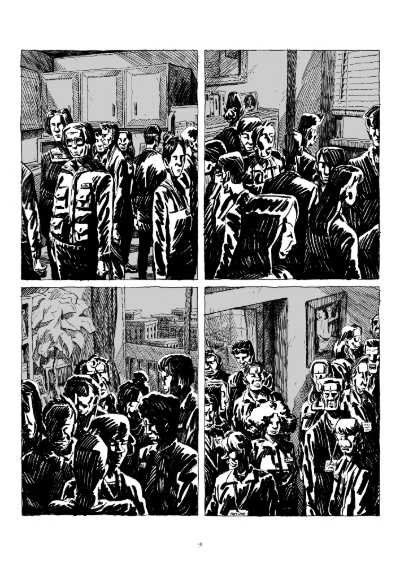

Kim has a distinctive approach to line. The majority of the book and the main characters themselves are rendered in the same light, thin, slightly shaky pen line that can be seen in Kim’s illustration work. A speculative line, perhaps, one that is trying to sketch and feel-out the form of things. The ominous figures are however rendered in thick black marker strokes; they are a darker, heavier presence, an intrusion that can’t be ignored, like a black spot of worry seeping over the mind, an anxious thought that won’t go away. They gradually become a dominating and debilitating presence in the character’s life, and that of his sister. Like oil, they swim and encircle the siblings as they speak in the apartment, or amass to watch, silently, as they argue on the balcony.

Kim has created an excellent and mature work here. I’d planned to space out my reading of the book over days but became so invested that I finished it in one sitting. There’s a degree of abstraction or an expressive quality to the story, to some of the events, certainly to some of the characters’ appearances, and of course to those dark figures from the past. But the narrative never flips over into being completely surreal. It feels grounded in the real world and remains relatable. There is also a richness and excess to Kim’s artwork, in the detail he gives to streets, architecture and interiors, and this gives the story’s setting a tangible sense of place. Rather than explain everything, Kim employs his artwork to do the most important storytelling, and he is excellent at this. There are also certain well-placed, recurring visual cues – a building site, a surface rupture – that collect and grow in significance as the narrative builds in intensity. It makes for a well-rounded and considered work and a powerful and emotional experience.

Chris W. Kim (W/A) • SelfMadeHero, £14.99

Review by Jon Aye