In 2017, Martine van Elk, professor of English at California State University, published a comparative study of early modern English and Dutch women writers. It documented responses by women to what domesticity meant in the seventeenth century and tracked the shift between public and private that took place, revealing how female writers reacted to it in incredibly complex ways.

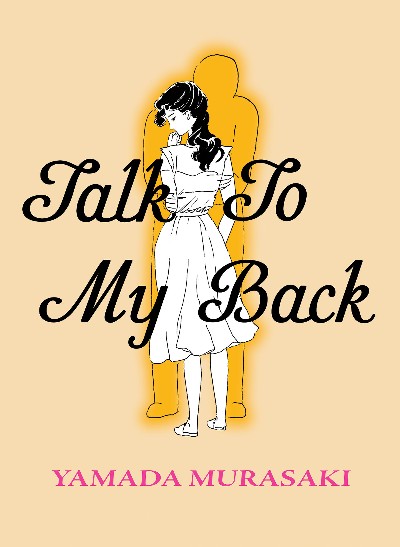

There is no way of knowing if Japanese writer and artist Murasaki Yamada (born Yamada Mitsuko) was familiar with the work of those early women, but there are strong parallels between them and her singular view of womanhood. We know this because of Talk to My Back, her short stories published between 1981 and 1984 in influential manga anthology magazine Garo, now accessible to English-language speakers thanks to translator Ryan Holmberg.

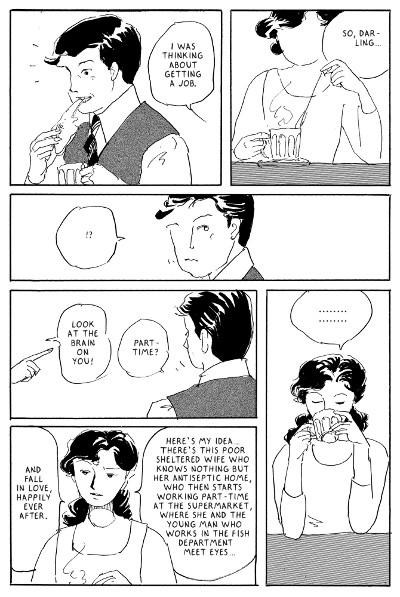

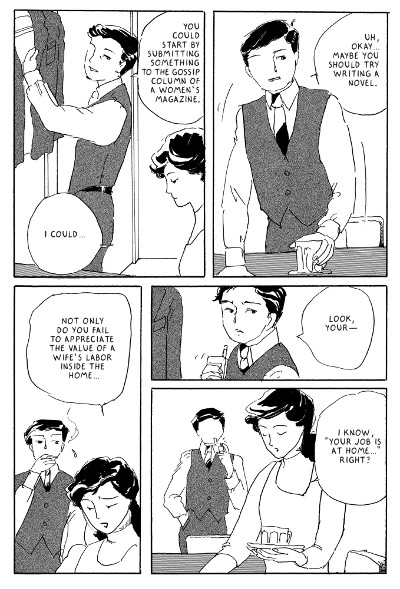

To call this a collection of short stories is imprecise, because so much of what Yamada attempted to capture took the form of vignettes. This doesn’t diminish their power though, as it allowed her to shine a light on the minutiae of life for a majority of Japanese women relegated to the drudgery of housework. Their husbands, by comparison, lived and worked in a state of freedom their wives had no access to.

Murasaki’s protagonist is the housewife Chiharu Yamakawa, and her world is restricted to two daughters, a husband who makes cursory appearances on late evenings and weekends, and rare interactions with passive aggressive neighbours struggling with their own forced isolation. Yamakawa is dissatisfied but can’t quite put her finger on what makes her feel the way she does. She knows she has more to offer, tries to change her circumstances by attempting to work part-time, but ultimately comes home to the only roles that define her, of wife and mother to three individuals who don’t know or particularly care about her feelings. She is lost but doesn’t know why.

These stories from the early 1980s seem startlingly of our time because of how Murasaki explores misogyny in a society that hardly appears to have changed in the decades since. Japan ranked 120th out of 156 countries in the World Economic Forum 2021 Global Gender Gap Report and had just 45 women elected to its 465-member House of Representatives a year ago. Set against those facts, it feels as if Murasaki’s housewives are stuck in a time warp that has barely stretched, their lives still cast aside to the margins of society.

One of the nicest things about this translation is Holmberg’s essay that places Murasaki’s pathbreaking role in alt-manga into context, showing why she was often ahead of her time not merely with her choice of subject but through the subtle ways in which she addressed questions related to feminist debates of the era. Her work was published during Japan’s post-war years, a time of economic prosperity that also saw extended arguments related to motherhood and women’s roles in the burgeoning labour market. To talk of feminism was difficult because it was a topic treated with much wariness, so for Murasaki to focus on a housewife’s depression, her reaction to infidelity, and her ambivalence about children was a ground-breaking act of artistic independence.

Holmberg’s essay quotes writers and editors who point out that Murasaki’s importance should have been recognised earlier. Better late than never.

Yamada Murasaki (W/A), Ryan Holmberg (T) • Drawn & Quarterly, $29.95

Buy Talk to My Back online here

Review by Lindsay Pereira

[…] Talk to My Back (Lindsay Pereira, Broken Frontier) […]