As the heartbeat of the adult Richard Grayson fades away in Forever Evil #6, our resident researcher in the Golden Age and Silver Age of comics – Joe Krawec – brings us her thoughts on why Robin was such a necessary inclusion in Batman.

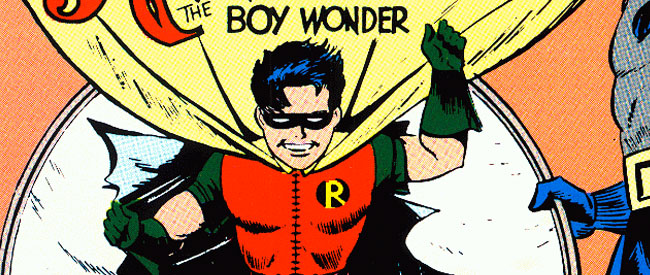

Long before Peter Parker reflected on the great…responsibility that had fallen upon his young shoulders, there was another boy whose role it was to teach the world about growing up in a man’s world. In 1940, a group of men working at what would later become DC Comics Inc. decided that the kids of America needed a character they could relate to; a child-hero. This child would be typical of DC’s readership, so that when he looked over and grinned at the adult swinging through the air by his side, he would be staring with the eyes of pre-teen America. And so it was that DC chose a young man by the name of Richard (Dick) Grayson to take on this defining role. Grayson became Robin, the Boy Wonder.

The stories of Dick Grayson in the first twenty years or so of his career contain some beautiful tales. As a new reader of comics, this young man proved to be a revelation to me. I shall never forget my joy as I read his exploits for the first time, or the sadness he made me feel. He truly is a Wonder. The reason for this is simple; Grayson’s life is kind of lesson in growing up in 40s and 50s America. He teaches us both what being a child may have been like back then, but also about what people thought childhood should be like. As history is the story of human development, some of these ideas and experiences of childhood are different to our perception today. But make no mistake: although “the past is another country”, some concepts remain eternal. Richard’s stories still have huge relevance, therefore.

Lesson #1: How We Fail Our Children

Richard’s age is not given in his first appearance in Detective Comics #38, April 1940, but canon has since determined that he was twelve years of age when he became Robin. For a boy like Dick Grayson – the product of a largely Jewish male workforce at DC – it is the year before his bar mitzvah. For the rest of us, twelve is the year in number before teenhood, puberty and all that problematic ‘stuff’. Thus twelve is when a young person stands on the cusp of burgeoning responsibility, independence and assuming control over one’s destiny. Nevertheless, a boy of twelve is a still minor. He may have very definite ideas of who he is right now and who he wants to be in the future, but he is not yet free to choose that path. Instead, he is subject to the care and rules of adults who, as many of us unfortunately attest to, do not always act in a child’s best interests. And there is no better lesson in how we fail our children than the origin of Richard Grayson.

Richard’s father and mother – ‘The Flying Graysons’ – are murdered because of the enforcement of a protection racket. This is the consequence of adult behaviour; of a group of ‘grown-up’ gangsters headed by a man named Zucco. When Dick learns the truth about his parents’ death he is determined to go to the police with the incriminating information. However, Batman persuades him not to because:

“This whole town is run by Boss Zucco. If you told what you knew you’d be dead be dead in an hour.”

This is one of the most significant statements in the whole of Batman. Adult society not only fails to safeguard the lives of the Graysons, but also denies them justice. The only way that Dick can secure a conviction of these murderers is by becoming a masked hero – the type of character that children’s playtime is filled with. Adults are the cowardly, superstitious lot, tainted by corruption and vice. If we want the world to be a better place, then a twelve year-old boy is the ideal candidate to make that utopia happen.

Society also failed the other little boy who Robin fights alongside with – Batman.  Batman is an eight year-old child inhabiting an adult’s body. When Bruce witnessed the murder of his parents he swore that he would devote his life to fighting criminals. But unlike the rest of us who would either quietly forget or become an institutional crime fighter such as a policeman, Bruce donned a mask and cape and lived out his playtime dreams. Just because Batman is dark and frightening does not exclude him from childhood. Children all too readily feel pain and understand the consequences of loss, the thrill of fear.

Batman is an eight year-old child inhabiting an adult’s body. When Bruce witnessed the murder of his parents he swore that he would devote his life to fighting criminals. But unlike the rest of us who would either quietly forget or become an institutional crime fighter such as a policeman, Bruce donned a mask and cape and lived out his playtime dreams. Just because Batman is dark and frightening does not exclude him from childhood. Children all too readily feel pain and understand the consequences of loss, the thrill of fear.

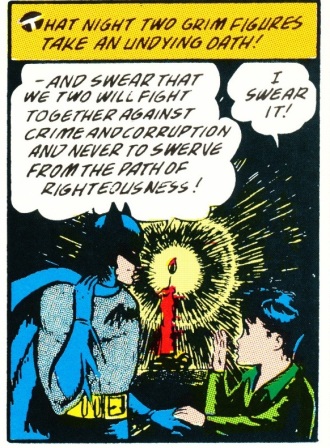

So when Batman relates his own tragic story to Dick, the boy becomes determined to live the superhero life. Batman – to his credit – is reluctant to take Richard on, but Grayson persuades him to do so. By candlelight, Batman and Robin swear ‘an undying oath’ ‘never to swerve from the path of righteousness’. These two BFFs are thus joined forever in the kind of secret club pact that little boys and girls make every day the world-over.

Lesson #2: The Kids Know Best

When Richard first became Robin, society had defined the journey from birth to adulthood as including only these elements. A person was a child, then a grown-up; the word ‘teenager’ was still a decade away from reaching people’s lips. But this is not to say that young people did not exhibit all the behaviours we associate with teenagers – rebellion, introspection, being-a-pain-in-adults-asses. The history of crime in American cities is that of the teenager-to-early-twenty-year-old, of young gangsters making notorious names for themselves. Furthermore, comic strips in newspapers (read by an overwhelming adult audience) teemed with smart-mouthed kids, usually from the rough side of town, like the Katzenjammer Kids.

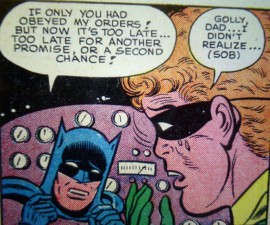

Young Master Grayson reflects this rebellious air. Dick is mostly permitted to show his distaste for adults by his treatment of criminals. There’s barely an issue of Batman that goes by without Robin likening some ugly goon to a monkey or elephant and it is very, very funny. But significantly, Batman also gets the brush-off. Richard often disregards his adoptive big brother’s orders, sometimes with positive consequences. Robin – the child – seems to know best, or at least has judgement as good as the adult hero. His disobedience leads to the solving of cases and the capture of those same ape-faced goons whom Grayson so loves to slap around.

Batman doesn’t take Robin’s disobedience lightly, though. I have lost count of the number of times Bruce threatens to whale on Richard for doing his own thing. Also, Bruce is pictured spanking Richard at least once to my knowledge. His methods of discipline utterly reflect the times. Though it can be said that Western history from the mid-nineteenth century can be defined by its increasing ratification of human rights, child-rearing in the US and UK at this time still overwhelmingly supported the use of corporal methods of punishment. The spanking question has still not gone away even now, with “To Train Up A Child” – a book that advocates corporal punishment methods for babies – being linked to a child’s death. So yes, Batman is a spanker. The fact that Batman also likes to spank criminals and especially Catwoman, is a whole other story, though.

Lesson #3: Being Young is a Struggle

The popular image of Robin remains the dutiful sidekick with cheesy ‘holy’ catchphrases, as immortalised by Burt Ward in the TV series. However, this obedient, unthinking Robin, so at ease with the role of superhero is not always reflected in the comics. In Batman #66 from August/September 1951, there is a tale that is almost forgotten about, but one that is amongst the most heartbreaking episodes in Batman history.

The popular image of Robin remains the dutiful sidekick with cheesy ‘holy’ catchphrases, as immortalised by Burt Ward in the TV series. However, this obedient, unthinking Robin, so at ease with the role of superhero is not always reflected in the comics. In Batman #66 from August/September 1951, there is a tale that is almost forgotten about, but one that is amongst the most heartbreaking episodes in Batman history.

“Batman II and Robin, Junior!” proves that the responsibility of being Robin is too much for any child. It brings together this theme with that of Grayson’s natural rebelliousness to devastating effect. In it, Grayson fails to follow an order from Batman and is admonished for it. This ‘failing’ by the boy is becoming a habit, it seems. Richard then has a dream in which his future, adult self is Batman and his young son is Robin. This fantasy child of Grayson’s disobeys an order his father gives him, the consequence of which results in their deaths.

On face value, this story seems like a 1950s lesson in the consequences of disobedience for young boys. Dick was growing up in a patriarchal age. 50s America was determined to prove that the American way of life was the only way and that way included an ideal home with mother, father and ‘daddy knows best’ as its core philosophy. But this story goes much deeper than that. Dick’s rebellious tendencies result in toxic genes; a horrible fate is imprinted in his bloodline. Those who perceive the Golden and Silver Age of comics as childish or simplistic are not reading the stories with the respect they deserve.

In this example, Dick Grayson is suffering from acute levels of anxiety for acting as all kids do – a bit naughty and dismissive of ‘the olds’. But Richard isn’t allowed to act like his readers who get to say, ‘Later dad! I’m reading Batman!’ when their parents ask them to take out the trash. For Batman and Robin, later means dead. This is Richard’s insight into the world of being the child-hero.

Lesson #4: Robin Makes Batman More Batman!

Let us not forget that there are two experiences of childhood – that of the child and that of the parent. If we choose to have children, we hope that the experience is going to be a happy one. Certainly amongst my peers, child-raising is expressed as the most rewarding experience a human can enter into. To fully understand Richard’s childhood, therefore, we need to look at it from Batman’s point of view.

As I stated, Batman can be seen as the eternal little boy, but his duty towards his young ward is very clear. Bruce, along with Alfred from 1941, provides the adult care for Richard. For some fans, Robin’s inclusion in the Bat-verse is an annoyance, not in keeping with the Bat’s lone wolf ethos. It is true to say that in my research year of focus – 1939 – Batman is a very different beast to the man who teams up with Dick Grayson. But I have to say that, whilst 1939 Batman has a certain grim enjoyment, he can also be terribly boring. I often liken 1939 Batman to a black hole in deep space, with nothing in its gravitational pull.

To the naked eye, all we see in that situation is blackness. But as soon as a bright star falls victim to the black hole’s wake, we see the phenomenon clearly because we are able now to perceive its effect. That bright star is Robin. We know that Batman can be grumpy because he admonishes Robin. We know that Batman likes to be punctual because he shouts at Robin to be on time. We also know that Batman likes to make a joke when punching goons because it makes Robin laugh. The Robin dost maketh The Batman.

Lesson #5: Families Wear Pyjamas

Some fans may not like Robin, but it has to be said that Batman does. Batman loves him. This is not the kind of love that Wertham accused him of in Seduction of the Innocent. The allegation of homosexuality in their relationship shows a breathtaking level of cultural ignorance. Quite apart from the fact that Wertham actually meant paedophilia (which is wrong, as opposed to adult male with adult male consensual sex, which is not wrong), Wertham’s example is laughable and easy to explain: ‘Batman and Robin share a bed’, ‘Batman and Robin are pictured wearing pyjamas’.

Some fans may not like Robin, but it has to be said that Batman does. Batman loves him. This is not the kind of love that Wertham accused him of in Seduction of the Innocent. The allegation of homosexuality in their relationship shows a breathtaking level of cultural ignorance. Quite apart from the fact that Wertham actually meant paedophilia (which is wrong, as opposed to adult male with adult male consensual sex, which is not wrong), Wertham’s example is laughable and easy to explain: ‘Batman and Robin share a bed’, ‘Batman and Robin are pictured wearing pyjamas’.

Yes – because they are family and this is what families once did and still do sometimes. When Bob Kane and Bill Finger were growing up in New York, overcrowding in the city (and many others across the world) was common. Low-income families had to make do, so siblings shared beds. My own father had to share a bedroom with his brother until he moved out to get married. It doesn’t matter that Wayne Manor has 99 unused bedrooms, 30s and 40s kids were used to sharing rooms with their older siblings and parents.

Lesson #6: Family is The Most Important Thing

Disgruntled fans may not want to read the 40s and 50s Batman books because Batman goes out of his way to show us just how much he loves the kid. Richard brings joy to the older man’s life just as much as any parent/carer hopes for. This goes back to Batman and Robin’s parallel origin stories. Adult society failed Bruce Wayne and Bruce’s promise to change this situation is a never-ending battle for him. But in Dick Grayson, Bruce has proof he has helped at least one child deal with loss. We may not agree with Bruce’s method – making a mini-me, a child soldier, actually – but Richard makes it clear that donning the cape and mask was his choice. Bruce is there to guide him through this, to keep him as safe as he can.

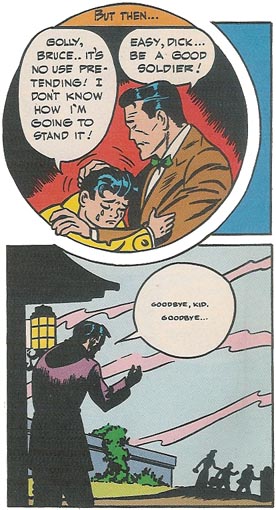

Far more than this, Richard gives Bruce what he has always longed for – a family. The ranks of Marvel and DC positively teem with orphans. It is the origin story de rigueur, a sure-fire way of getting any child-reader to understand why a hero must become so. After all, what is worst to a child than losing her parents? Richard thus helps to heal the wounds left in Bruce from that fateful night in Crime Alley by reconstructing a family for him. This is demonstrated by “Bruce Wayne Loses the Guardianship of Dick Grayson”, from Batman #20, December-January 1944. In this, Bill Finger, the creator of Batman tells us that:

“The Wayne home is a happy home, for in it lives a happy trio!”

“The Wayne home is a happy home, for in it lives a happy trio!”

This ‘happy trio’ is Bruce Wayne, Dick Grayson and Alfred Pennyworth. But all this is threatened when someone purporting to be from Dick’s family returns to claim Bruce’s young ward. There is a lot of crying in this story. Richard tries to be strong, but bawls nonetheless because he doesn’t want to leave. Alfred then joins in with the sobbing. By contrast, Bruce keeps a stiff upper lip. As we count down the hours to Richard leaving, he urges his young ward to be a brave little boy. But when Richard walks out the door to be spirited away from Wayne Manor, Bruce’s manly façade crumbles.

Wayne is pictured in shadow, but the tiny, trembling lettering of his farewell betrays his tears as he waves off his kid brother forever. Frankly – if you are not biting down on your lip to force back your own tears, then you have rocks for a heart.

Conclusion: Childhood is a complex thing

The lesson that Richard Grayson provides for us is that childhood then, as it is now, was a complex thing. Grayson is his own person, but is expected to fulfil a certain role, an expectation that he sometimes feels he cannot live up to. Despite public perception, he is as cheeky as he is obedient and as mischievous as he is dutiful. Though Richard benefits from the care of Bruce, it is the adult hero who wins most from their relationship. Batman benefits from having a family, but the whole character of the Dark Knight is made three-dimensional by Robin’s inclusion in the DC universe.

Most of all, Richard Grayson is a timely reminder of how we fail our children. The fact that any child feels obliged to don a cape and mask in order to secure his future is a terrible reflection on us all.

Great article. I go on a bit below, but you got me thinking and I wanted to share that. I definitely appreciate Robin more now because of you.

You presented two ideas new to me that help redefine Batman: Batman as an older brother to Robin, and Robin as the person who made Batman interesting.

I always thought of Alfred as a father to Bruce, but not to Robin. But you make it clear, Bruce can’t be a father to Robin. He’s an authority figure, but he’s too broken to serve as a parent. Which is why he allows Robin to join him; they’re two siblings sharing something, while a parent would never include their child in something like this.

Robin as the star – I never thought I’d see someone say that. I’ve heard it once or twice before, but only within the Bat-universe. Robin’s biography in the Arkham City video game describes Tim Drake as believing Robin is a necessary part of Batman. But, I thought, that’s just the writers trying to provide a reason for him to be there. Same must be true for Dick Grayson.

You made me think about that. Because, when I think of a solo Batman he’s just… nothing. Grim, brooding, crazy. All of his villains are colorful, but so is his family. They’re what brings out what’s left of Bruce Wayne, and Robin, as a child who suffered a similar tragedy, shows him he doesn’t have to be Batman all the time. That Bruce Wayne might have a life too.

What happens now that Grayson is gone?