“Is it about a bicycle?” he asked.

As a lover of tall tales, the first thing that bounced into my noddle when I picked up The Curious Case of Leonardo’s Bicycle was Flann O’Brien’s mind-bending classic The Third Policeman. And a quick glance at the summary of the book and the complex web of characters and connections outlined on the endpapers suggested that this could also be a bit of a shaggy dog story. However, as unbelievable as some of it may seem, the whole thing is an energetic and detailed graphic investigation based in a search for the truth.

A keen student of cycling culture and history, Brick – political cartoonist, comics creator (Depresso) and joint editor of the Eisner-nominated World War One anthology To End All Wars – has been researching the so-called Leonardo bicycle since the late 1980s. And across the book’s 250-odd pages, he spins a yarn that brings together academic antagonism, clerical corruption, urban terrorism, political upheaval and the biggest bang the world has ever felt…

The more metaphorical eruption at the heart of the book took place in 1974, when an Italian scholar, Augusto Marinoni, used a prestigious lecture to make a startling announcement. On the back of a page from one of Leonardo Da Vinci’s notebooks, he claimed to have found a crude but distinct sketch of a bicycle – more than 300 years before the accepted invention of what bike-lover Brick describes as “a piece of hardware more empowering for more people than all the democracies in history rolled into one”.

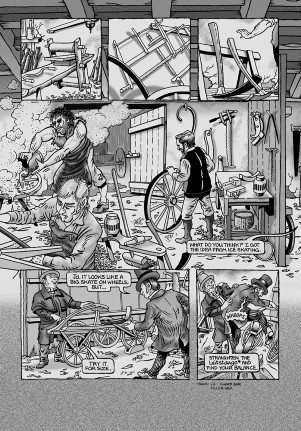

Brick digs deep to debunk Marinoni’s claim, supporting the alternative view that German civil servant and inventor Karl von Drais actually gave the world the bicycle in the early nineteenth century, in the form of his laufsmaschine, or running machine. In near-forensic detail, the cartoonist walks the reader through the provenance and history of the notebook at the heart of the controversy, the Codex Atlanticus, including its restoration at the secretive Grottaferrata monastery in the 1960s, after which Marinoni made his discovery and startling announcement.

However, Brick comes at his investigation from a dizzying number of angles. First and foremost, he places Marinoni’s revelation in the context of Italy’s gli anni de plombo, or ‘years of lead’ – a period of political and social violence that spanned the 1970s and left up to 1,500 people dead. He also highlights the country’s historical passion for sport in general, and cycling in particular. However, by the 1970s the glory days of Gino Bartoli and Fausto Coppi seemed a long way back. As Italian cycling hit the doldrums, maybe the country’s morale needed a boost…

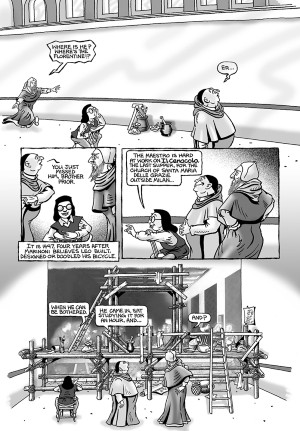

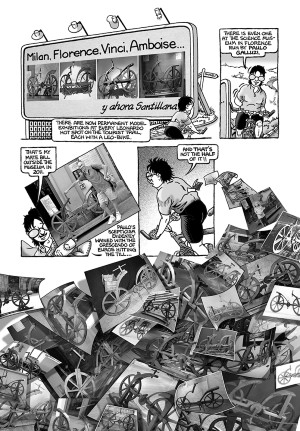

In a series of themed chapters, Brick heads forward and backwards in time to shed some light on every aspect of the controversy (inserting his bespectacled self into scenes and guiding the reader through what’s happening in a way reminiscent of Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics). Heading back to the 1490s, he looks at where the sketch would have fitted into Leonardo’s biography, concluding that such a profound invention would have been highly unlikely during a period of unpaid bills and unfinished commissions. Leaping back to the late twentieth century, he casts a jaundiced eye on the industry that has sprung up around the ‘discovery’, as manufacturers make bold assumptions about how to convert the sketch into a three-dimensional working model.

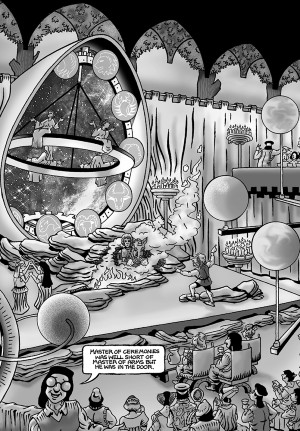

Alongside Brick’s core thesis, the book is replete with entertaining yarns that may seem slightly tangential but are delivered with humour and energy. These range from the unexpected global consequences of the Mount Tambora volcanic eruption in 1815 to the often bizarre ‘fringe’ theories that have sprung up around Leonardo and his work, and even the long and eventful saga of his bones.

I’m guessing that Brick is (like myself) of the generation that was captivated by James Burke’s seminal TV series Connections, in which the urbane presenter drew together unlikely historical elements to show how scientific and technological advances coalesced from a number of sources. Stirring a much bigger dollop of humour into the mix, Leonardo’s Bicycle works in a similar way, bringing in unexpected nuggets of knowledge to support Brick’s argument. His desire to nail a visual gag to every point doesn’t always hit the mark, and one unexpected use of a homophobic slur leaves a bad taste, but the artist’s conviction, energy and invention drags the reader along the story’s complexities and cast of thousands.

The obfuscation surrounding the sketch and its provenance (an age test was finally undertaken in 2009 but the results never released) means that no conclusive verdict can be reached. However, Brick delivers his case with confidence, ultimately reserving his fiercest scorn for those who have picked up the apparent fraud and profited from it: “the bel casino [beautiful confusion] will rumble on… money will be made and people duped”. This is a dense and entertaining piece of graphic investigation that will give the intellectually curious reader plenty to chew on.

Brick (W/A) • Brickbats, £20 (discounted to £15 for limited period)

Review by Tom Murphy