In April 2024, the Governor of Japan’s Shizuoka Prefecture was compelled to announce his resignation after making a speech that sparked debate across the country. Apparently, while speaking to newly inducted civil servants, he compared their intelligence to that of people engaged in perceived lowly professions like manufacturing. It was a stark reminder, for residents as well as outsiders, that Japan’s political landscape has never broken free of hierarchies that have been in place for centuries.

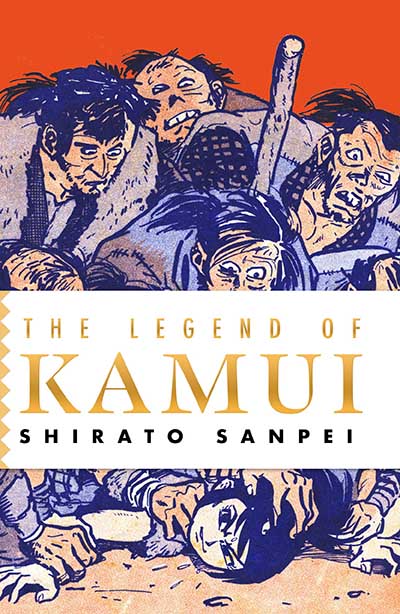

Those hierarchies come to mind repeatedly while reading Shirato Sanpei’s The Legend of Kamui. Serialized between 1964 and 1971 in legendary monthly Garo — a magazine that, incidentally, took its name from one of Sanpei’s characters — the manga has finally been translated into English by Richard Rubinger and Noriko Rubinger, with Alexa Frank.

Set in seventeenth century Japan, Shirato’s political allegory was born out of his childhood experiences in the immediate aftermath of World War II. He was 32 years old when the first volume of Kamui Den appeared, and the manga’s setting in the feudal Edo period served as ongoing commentary on the class struggles that still weighed heavily on the minds of young people.

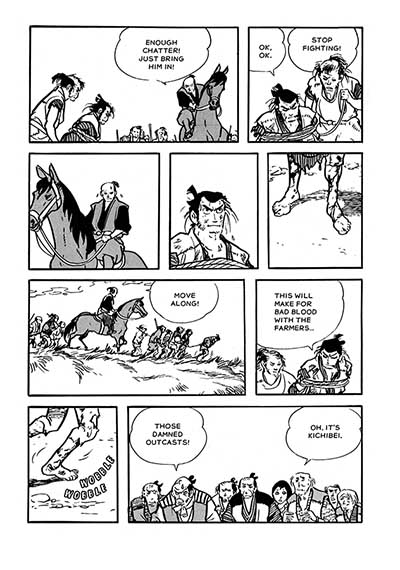

Spread across six chapters, this first volume introduces readers to the titular child born on the fringes of society. Left with no choice, he chooses the path of the ninjas a way out, drawing attention not just to the violence of the age, but to the ways in which society allocated resources to a chosen few based on a system that placed little value on merit. It is interesting to consider that the years during which Kamui was published coincided with intense political turmoil in Japan. It was a decade marked by mass protests, transport disasters, as well as economic growth. On the one hand, those years birthed the world’s fastest trains, saw Tokyo host the Olympics, and introduced the country to The Beatles. On the other, it saw artists like Shirato railing against a system that excluded many from access to the same economic advantages.

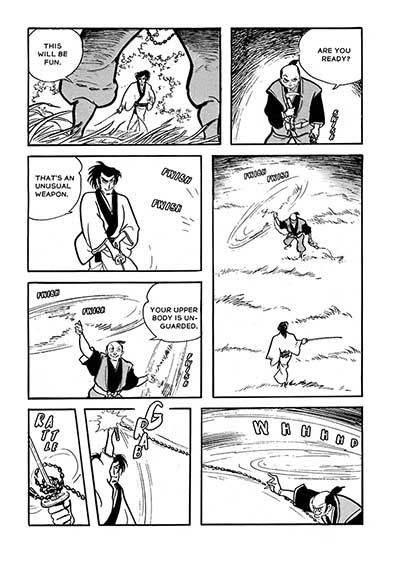

Shirato never hid his Marxist leanings, but it is to his credit as an artist that ideology never overwhelms his art. Kamui is almost like a soap opera, full of twists and turns, action, and even humour. Political commentary aside, it is a very good story, which makes the appearance of Volume Two in the summer great news for anyone who gives this a chance. There is a lot of brutality in these pages, both literal and metaphorical. Shirato depicts not just the dismal lives of farmers condemned to till land for the upper class, but also the limited options open to those who dared to break free of shackles imposed purely by accidents of birth.

The Legend of Kamui isn’t exactly the story of one person, given the smaller plots and allegories that run alongside the main narrative. It operates like an ensemble, building a collective portrait of society with many threads. There is life and death here, but also asides about racism, materialism, the indifference of nature and cruelty of mankind, all depicted in a raw, almost fluid style that would go on to influence a generation of mangaka.

Shirato—who passed away at 89 in October 2021—ended each chapter with short essays that made his position explicit. Consider, for example: “If everyone’s legitimate demands were crushed and ignored, how sad and indignant we would be! Today, despite all the advancements in society and people’s desire to lead happy lives, reality falls short of these expectations.” What is startling about those sentences is how apt they seem right now, in Japan and around the world, as systems that pit rich against poor appear to be stronger than ever.

Shirato Sanpei (W/A) • Drawn and Quarterly, $39.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira

[…] The Legend of Kamui, Vol. 1 (Lindsay Pereira, Broken Frontier) […]