Having worked previously with collaborators from Shakespeare to Alan Moore, artist Oscar Zarate takes the reins with The Park, a beautifully observed and crafted tale of retribution and redemption in one of London’s wild places.

Given his prodigious talent and criminally low profile, there’s an argument that Oscar Zarate, an Argentinean settled in London, is the best comics artist you’ve never heard of. Admittedly he hasn’t been the most prolific creator over the years, but the quality of his work and the status of his collaborators surely should have pushed him to greater recognition.

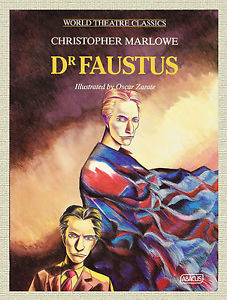

His lush but generally straightforward adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello (Pan Macmillan, 1983) was followed by an altogether more exciting version of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (Sphere, 1986). Ahead of its time, this was a visually stunning and telling transposition of the story into the unfettered greed and social chaos of Thatcher’s Britain, together with a Bowie-esque Mephistopheles.

His lush but generally straightforward adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello (Pan Macmillan, 1983) was followed by an altogether more exciting version of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (Sphere, 1986). Ahead of its time, this was a visually stunning and telling transposition of the story into the unfettered greed and social chaos of Thatcher’s Britain, together with a Bowie-esque Mephistopheles.

The following year he collaborated with comedian (and now novelist) Alexei Sayle on the caustic satire of Geoffrey the Tube Train and the Fat Comedian (Methuen, 1987) – another visual tour de force that remains unexpectedly out of print. (As any Londoner will attest, the denizens of ‘New Stokington’ certainly haven’t got any less awful over the past 26 years…)

Perhaps his highest-profile work was A Small Killing (1991), a collaboration with Alan Moore than formed part of Gollancz’s pioneering but ultimately premature attempt to produce a line of graphic novels for mainstream readers. Having drifted in and out of print over the years, the book – which tells the tale of a successful advertising executive being stalked by a mysterious boy – marks an interesting psychological study and a strangely over-looked part of the writer’s work.

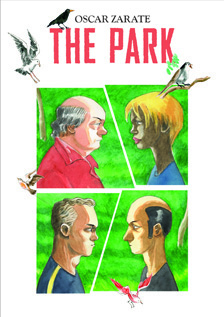

While Zarate has been a prolific book illustrator since then, it took until late last year for him to produce what I believe is his first solo long-form comics project – The Park, published by SelfMadeHero.

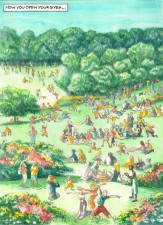

The Park of the title is more correctly Hampstead Heath, the wild expanse of greenery that spreads for 790 acres across affluent north-west London. The book is a carefully observed meditation on an aspect of London life that sets the city apart – its parks, where “woodland, wildlife and people meet together in the middle of the city”.

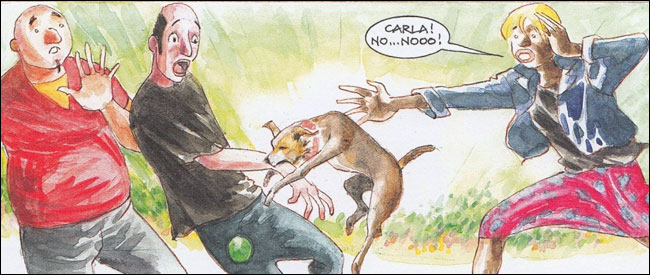

Slightly reminiscent of the acclaimed Australian novel The Slap, by Christos Tsiolkas, Zarate’s book focuses on the ripples that spread from a single violent encounter. Postman and musician Chris Stein (not that Chris Stein) is walking on the Heath one day when he’s bitten by the out-of-control dog of Ivan Grubb, a tiresome self-styled ‘voice of the people’ journalist. When Chris kicks the dog away, Grubb punches him.

The incident exerts strain on the family relationships of the two men, who are both single parents to grown-up children. Grubb’s graffiti artist daughter Mel is critical of her father’s violent over-reaction, while Chris’s son Victor, a personal trainer, thinks his own father weak for not fighting back or demanding an apology. Victor subsequently decides to enact his own retribution on Grubb.

As you’d expect from a creator as experienced and accomplished as Zarate, The Park is a dense and rewarding read, more deserving of the ‘graphic novel’ label than a lot of books that carry that tag. Zarate marries plot, character, theme and imagery with great skill, focussing particularly on the problems caused by male pride and aggression.

Like British creator Jon McNaught (Dockwood), Zarate also has a great sense of location and, more particularly, the natural world that surrounds us even in the most urban of settings. Reflecting the central clash between Chris and Grubb, Zarate reminds us that nature is full of confrontations and battling males; we see fights for dominance among robins and stag beetles, while Grubb’s dog Clara is fighting the war that never ends against the birds of the Heath’s ponds.

The everyday landscape also becomes symbolic in Zarate’s hands: Victor finds himself in the dark of the woods as he considers exacting revenge on Grubb, and the Heath takes on a very different atmosphere between the sunbleached summer days and the dark, enveloping nights. As Victor comments on the noises of the Heath during his night-time runs: “It’s not just trees rustling in the wind. Something else is going on, beyond us.”

Zarate’s lush artwork is a treat throughout. Apart from the exquisite choices of storytelling and imagery, his expressive, almost Fauvist use of colour jumps off the page. He also has a gift for character; there’s nothing generic about any of the people who inhabit The Park, even those who just appear for a moment. They all drip with personality and life.

As the book nears its conclusion, Grubb and Chris meet up again. Each fuelled with a new gutful of resentment, they resume hostilities in an absurd, tragic-comic reflection of the slapstick scrap between Laurel and Hardy in the short film You’re Darn Tootin’, which Chris keeps watching (a fight which escalates to involve a whole town, in the same way the disupte between Grubb and Chris spreads to envelop those around them).

However, for all its richness, the book isn’t without flaws. As excellent as Zarate’s English is, some of the dialogue and narration occasionally betrays the slight awkwardness of the non-native speaker. And in a book that swings strongly on the notion of random encounters in a city with millions of people, there’s something a bit convenient about the way Mel and Victor are thrown together (however pleasing it is in terms of narrative symmetry). Finally, the book closes with a bit of imagery that seems slightly lacking in subtlety in comparison with what we’ve seen earlier.

Nevertheless, The Park is a fine and relevant piece of work, addressing serious themes of character, retribution and redemption in an accessible but thought-provoking way. Let’s just hope we don’t have to wait as long for Oscar Zarate’s next book.

Oscar Zarate (W/A) • SelfMadeHero, £15.99, October 2013