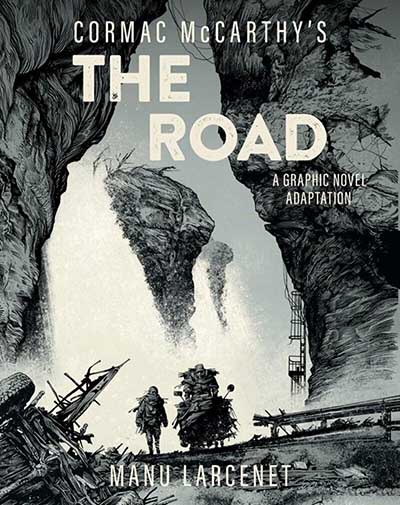

There is a little detail on the first page of this graphic adaptation, a blink-and-miss-it silhouette of a man holding a child’s hand. That it says so much is testament to the raw power of Cormac McMarthy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning classic, undiminished almost two decades after it was published. There are all kinds of reasons why this adaptation need not exist, starting with the fact that a lot of people may have read the original by now, or that those who haven’t may well have watched the film that appeared three years after the novel.

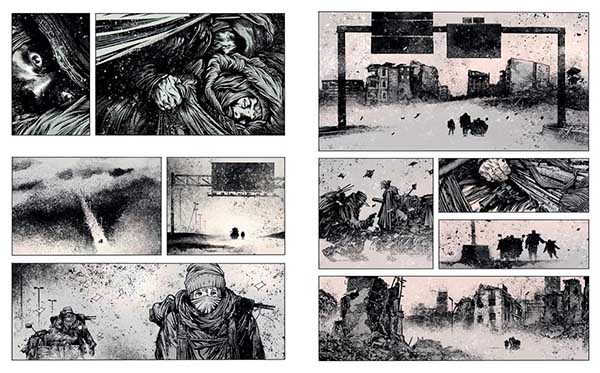

And yet, as one goes through French artist Manu Larcenet’s bleak yet powerful panels, this argument starts to render itself obsolete. The book comes alive again, plunging the reader into a post-apocalyptic world that seems more plausible than ever in our time of genocide, extreme rainfall, and super storms.

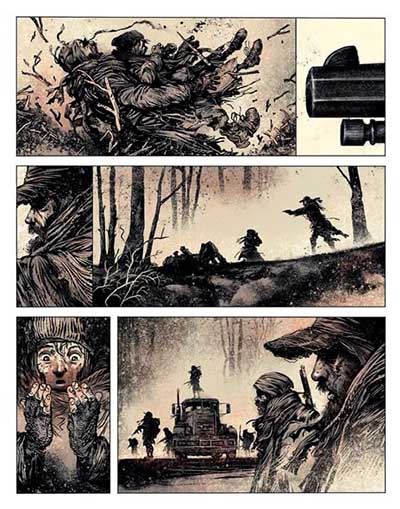

The Road has sometimes been described as an ecological parable and, at other times, a tale of hope that springs from despair. It is all this and more, because great literature lends itself to multiplicity when it comes to interpretation. It is endlessly adaptive, allowing the religious to treat it as a morality play, and the godless to praise it as a warning that there is no afterlife. As an artist, Larcenet is compelled to focus less on what is being said than how the novel’s inner world reveals itself. In a recent interview, he cited the work of 19th-century French illustrator Gustave Doré as an inspiration, and the influence is palpable.

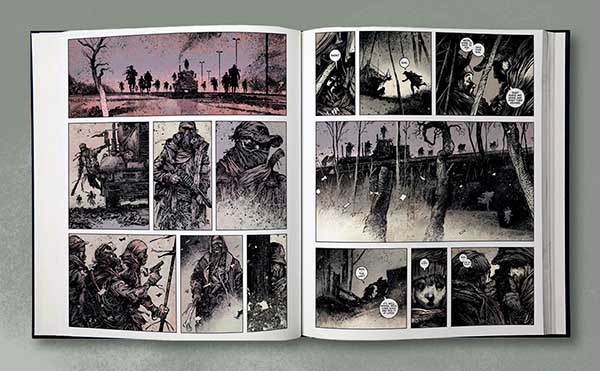

As an aside, it is worth noting that Larcenet has spoken of his struggles with anxiety in the past, explaining how he has countered it by finding ways of expressing himself. The nature of that expression seems almost tailormade for McCarthy’s desolate worldview. That desolation is a theme running through these pages, aided by claustrophobic close-ups and visual renditions of the kind of austere weather predicted for our near future. Larcenet also uses colour to his advantage when, for example, he lights up a single can of soda in an otherwise grim double-spread. There are multiple wordless panels, standing in for profound silences and adding to an overall effect of being in a pitiless, violent world where all lines of decency and morality have long been erased.

Does it work as well as the novel? That is debatable, because McCarthy’s immersive prose doesn’t always lend itself to a visual version. It forces the story to move along a little faster than the presence of long, descriptive passages allow, but that is probably an unavoidable challenge for any adaptation. It doesn’t take away from how Larcenet effectively latches on to the plot’s central idea.

In October 2007, the British environmentalist George Monbiot wrote about The Road, calling it ‘the most important environmental book ever written.’ He mentioned how the collapse of the protagonist’s core beliefs mirrored the shrinking of our biosphere, and how this loss was starting to show in our own time. What Larcenet does is what all political art is meant to — draw attention to the message by using a given medium as effectively as possible.

According to the publishers, McCarthy approved of this adaptation before he passed away in 2023, something he presumably would not have committed to without faith. Now, with the result in one’s hands, it’s easy to imagine why he would be pleased.

Manu Larcenet (W/A) • Abrams, £18.99

Review by Lindsay Pereira