Dreams are the way they are because they operate at the intersection of the left and right sides of the brain, the place between the soup-like repository of experience and our compulsion to organise the world into something resembling logic and structure. Freud’s theory was that the content of dreams was too troubling for us to face, and we instead sought to suppress this content by overlaying it with an internal filter, causing it to seep out in a mutilated and distorted form. Jung, on the other hand, believed dreams actually manifested in their most efficient form, taking a chaotic mess of information from our subconscious and mapping it onto imagery in a way that is symbolic and essentially narrative in form.

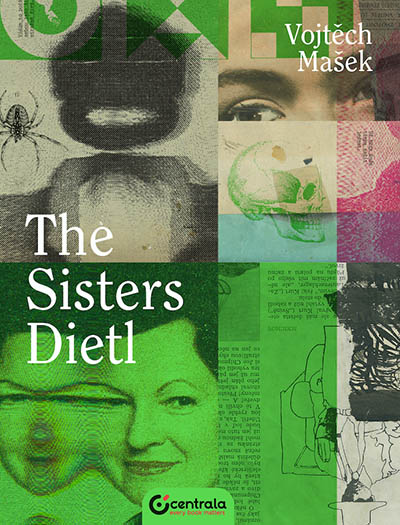

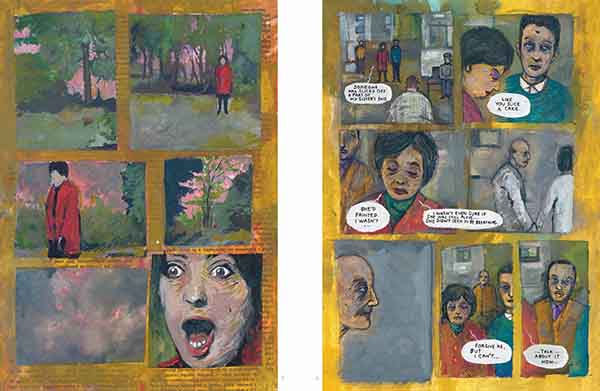

And so it goes with Vojtěch Mašek’s The Sisters Dietl. The book’s first pages resemble a grimy and well-worn scrapbook, with found imagery and pieces of text overlayed as if collaged together. This could be the results of an investigation, an assembly of archival material, or perhaps the unearthing of archetypal symbolism rooted in some collective unconscious. It sets the tone for what’s to come, both in the bristling sense of unease generated by the scraps of imagery and text and the approach to groping at meaning through the assembly of found material – as we read in one image, ‘more like fragments from a dream’. The collaged pages return throughout the book as chapter breaks, functioning like a persistent, background white noise that occasionally expels an image or word more salient to the narrative.

The sisters of the title are identical twins – doppelgängers, one of the sources of Freud’s sense of the uncanny. After having lunch with her friend Josefa, Vera Dietl is attacked and mutilated in a park, a section of her face sliced away ‘like you slice a cake’. She is found, still alive, by her sister Veronika and taken to hospital.

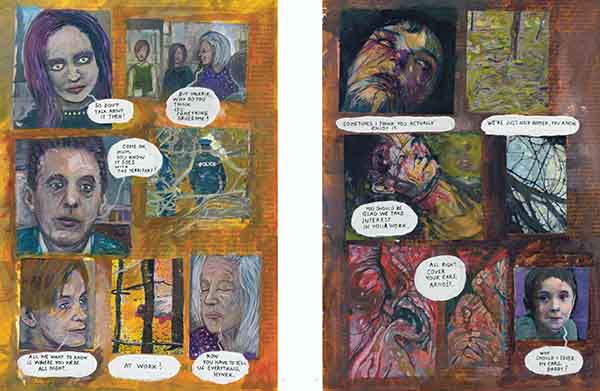

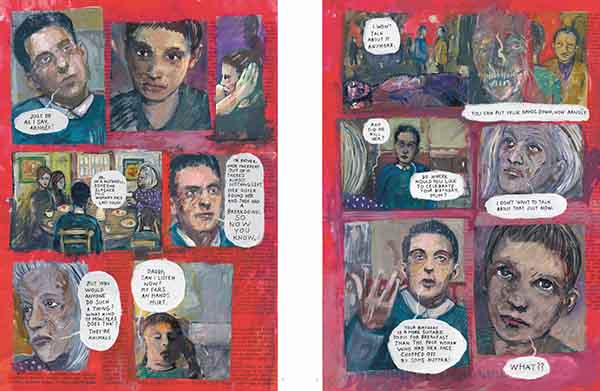

Sergeant Hoffman and Inspector Zinner, leading the subsequent investigation, are the book’s protagonists, but in truth, except for possibly Hoffman and one other character – a nurse at the hospital – we’re never made to feel particularly at ease in the presence of anyone in the book. It feels as if we’re never more than a panel away from a friendly face twisting into a sinister grin. Men in particular are a source of fear and mistrust, either through their direct behaviour or through a lurking, malevolent presence that they cast around the periphery. Women, by contrast, are most often the victims of violence, neglect or abuse. At one point Vera Dietl imagines her aggressor in a dream, his face a mess of scars and stitched-together skin – a composite man.

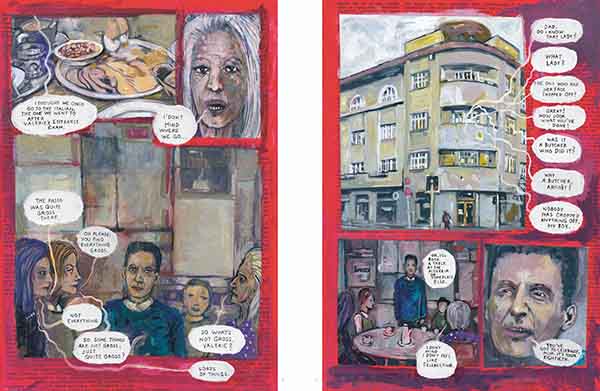

Mašek renders the art work of the main story in paint, with a thick impasto style that varies between fairly loose, expressive brush work to more tightly controlled and detailed scenes that incorporate pen lines and hatching – somewhere between Richard Diebenkorn and Jenny Saville, by way of Max Beckmann. What’s more notable is that many of the characters appear to closely resemble real-life actors: Hoffman is clearly based on John Turturro; Igor, a waiter in a café, is based on Willem Dafoe. I also recognised John Malkovich with a moustache and I think Robert De Niro appears in one panel, stirring a cup of coffee. Many of these characters, and some landscape scenes, in fact appear to be rendered through paint applied directly on top of photos. This seems more than just a novel approach to characterisation; it seems to fit the conceit whereby the book is operating like a dream, with its imagery and narrative mapped onto pre-existing material. After all, that’s what happens in dreams: they are a collage, an assembly, populated by figures and scenes we have seen before, but recast into different roles.

The wet-on-wet, impasto painting also works to add a fleshy aspect to the characters and the world they live in, which heightens a certain gruesome corporeality that underpins events. This begins with the slicing of Vera Dietl’s face and continues through its lengthy surgical reconstruction and a key plot thread involving a regular night-time gathering of the victims of grotesque mutilation.

The book is certainly engrossing and I found myself compelled to follow these police officers as they travel deeper into a darkening mystery, with connections to occult beliefs and the eugenic practices of the Soviet Union. Some things however feel more questionably rough or unrefined. There is the occasional repeated word in a speech bubble, for example, which comes across as a mistake in transcription. There is also a mysterious side plot concerning Inspector Zinner that is presented as of consequence to the main narrative. When it is revealed however, in a confrontation between Hoffman and Zinner, the resulting conversation happens quickly and feels like a slightly clunky bit of exposition.

There are some other loose threads, but it could be argued that these are part of the book’s aesthetic – the impulsive turns and imperfect reveals as things spill forward from the unconscious. Ultimately it’s clear that Mašek has a handle on his subject matter and we are led towards a suitably twisted and chilling conclusion to this dark, brooding and atmospheric story.

Vojtěch Mašek • Centrala, £29.99

Buy The Sisters Dietl online here

Review by Jon Aye

[…] Zoomed in, the confection is grotesque archeology, exposing layers of sweetness and goo. The waiter, who resembles actor Daniel Defoe, has a smile that is a little too wide to be entirely friendly. This accumulated, lush detail feels like too much and conveys the profound feeling that we are in the realm of dreams and nightmares. […]