Earth 2’s new Superman, created by Tom Taylor, is an unashamed return to the character’s role as a symbol of hope; untempered by the cynicism and post-modern deconstruction of the past twenty years.

Something is wrong with Superman. In fact, something has been wrong with Superman for twenty years. The Man of Steel is one of the DC Universe’s first and greatest heroes, using his array of extremely powerful abilities to defend his adopted homeworld from all manner of threats. But beyond his immense power, Superman’s strength resides in his role as a symbol of hope. Where Batman inspires fear in criminals, and the Green Lantern – as a member of an intergalactic police force – apprehends and punishes criminals, Superman does what he does out of a genuine belief in the inherent goodness of people. He is one of the few superheroes with a truly positive opinion of humanity. His mythology lives up to the emblem on his chest; the Kryptonian symbol for hope which serves as the shield of the House of El.

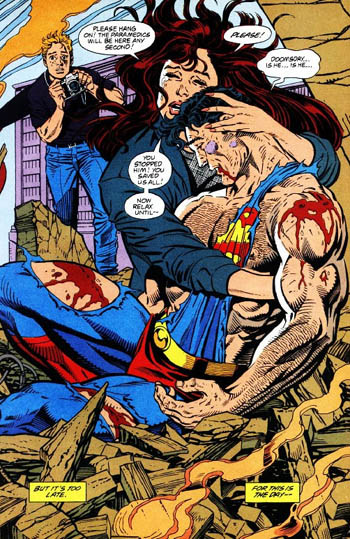

For the past twenty years, however, hope has taken a serious backseat in the character’s mythos. Though Superman stories remained fairly steadfast through the anti-heroism of the Bronze Age of Comics, they reached a breaking point in 1992 when Superman died defeating the savage Kryptonian monster Doomsday. The event posed the question of what fills the void left by an absent Superman; a question that – for the past two decades – has eclipsed the quotidian optimism of the Man of Steel, presenting in its place a barrage of cynical anti-heroes, despotic psychopaths, and other well-intentioned menaces to society meant to deconstruct Kal-El of Krypton.

For the past twenty years, however, hope has taken a serious backseat in the character’s mythos. Though Superman stories remained fairly steadfast through the anti-heroism of the Bronze Age of Comics, they reached a breaking point in 1992 when Superman died defeating the savage Kryptonian monster Doomsday. The event posed the question of what fills the void left by an absent Superman; a question that – for the past two decades – has eclipsed the quotidian optimism of the Man of Steel, presenting in its place a barrage of cynical anti-heroes, despotic psychopaths, and other well-intentioned menaces to society meant to deconstruct Kal-El of Krypton.

But Superman’s long mythological crisis may just be on the verge of resolution, and it comes in the most unlikely of forms: Val-Zod of Earth 2.

In the parallel universe designated Earth 2, Val-Zod was effectively orphaned when his parents were imprisoned for speaking out against the ruling authority of the planet Krypton. He was adopted by Jor-El and Lara, who saved him from the destruction of Krypton the same way they saved Kal and Kara, aka Superman and Power Girl; they placed him in a rocket and sent him to Earth. Somehow, Val ended up in captivity, a secret prisoner of Terrence Sloan in the World Army’s mobile Arkham Base. His years of solitary confinement resulted in acute agoraphobia. He was never exposed to the yellow sun and therefore did not develop his Kryptonian powers until he was discovered and freed by the Wonders of the World.

Val-Zod represents the rebirth of Superman, but in order to fully understand his significance we must first understand the broken mythology of Kal-El.

Kal-El’s death in 1992 was as much a symbolic death as it was a literal one. It presented a world in which Superman’s presence could no longer be felt and from that moment on the perspective never switched back. The subsequent deconstruction of the Man of Steel can be broken down into a couple of broad categories: that of philosophy, in which Kal-El’s traditional optimism and faith in humanity falters; that of morality, in which his acts, though technically heroic and done in the name of good, come at a high cost to his traditional moral standard; and that of being, in which his inherent goodness is called into question or thrown out the window entirely.

The most palatable of the three, the philosophical deconstruction of Kal-El is also the most prevalent. The portrayal of the character in Man of Steel is a terrific example; Kal is deeply distrustful of humanity, in large part due to the cynical world view of Jonathan Kent. This doesn’t come at the expense of his morality, but it shows in his initial hesitation to either cooperate with or confront Zod. Another good example is Superman Red/Superman Blue, in which the Man of Steel not only has his traditional powers replaced with ones derived from electricity, he is also split into two distinct beings. Superman Blue was the more thoughtful, calculating, and creative of the two, while Superman Red was impulsive, decisive, and aggressive – in many ways the dynamic mirrored that of the heroes Hawk and Dove, the avatars of War and Peace, respectively. These are vivid examples, but the deconstruction of Superman’s personality pervades the majority of his mythology for the past twenty years. From doubting his own place in society to lapses in his faith in humanity, the hope that epitomized Superman has gradually been worn down, neutering his symbolic importance and making him just another cynical (or “realist”, if you prefer) superhero.

The most palatable of the three, the philosophical deconstruction of Kal-El is also the most prevalent. The portrayal of the character in Man of Steel is a terrific example; Kal is deeply distrustful of humanity, in large part due to the cynical world view of Jonathan Kent. This doesn’t come at the expense of his morality, but it shows in his initial hesitation to either cooperate with or confront Zod. Another good example is Superman Red/Superman Blue, in which the Man of Steel not only has his traditional powers replaced with ones derived from electricity, he is also split into two distinct beings. Superman Blue was the more thoughtful, calculating, and creative of the two, while Superman Red was impulsive, decisive, and aggressive – in many ways the dynamic mirrored that of the heroes Hawk and Dove, the avatars of War and Peace, respectively. These are vivid examples, but the deconstruction of Superman’s personality pervades the majority of his mythology for the past twenty years. From doubting his own place in society to lapses in his faith in humanity, the hope that epitomized Superman has gradually been worn down, neutering his symbolic importance and making him just another cynical (or “realist”, if you prefer) superhero.

The deconstruction of Superman’s morality has been an especially popular take in recent years, with Superman: Red Son and Injustice: Gods Among Us serving as the two clearest examples. In the former, the baby Kal-El crash lands in the Ukraine instead of Kansas, and is subsequently raised in the Soviet Union under those values. He is a hero, but is morality is dictated by the context of his upbringing; he routinely lobotomizes dangerous criminals and political dissenters so that they no longer pose a threat to public safety. In Injustice (both the video game and the tie-in comic), the Joker manipulates Superman into killing Lois, her unborn child, and all of Metropolis, after which Superman kills the Joker and assumes political control of the world.

Once again, his actions are taken in the name of justice, safety, and the prevention of further horrors; the irony, of course, is that in suppressing freedoms and taking all aspects of the law and judgment into his own hands, Superman becomes the force he had previously fought against. A more minor, but heavily recurring example of this questionable morality is in Superman’s use of the Phantom Zone. Dangerous cosmic threats such as Zod, Mongul, and many others have been sent to the Zone and though it is an alternative to killing, there is no trial nor due process to regulate or govern its use. It is a substantial grey area in the normally clear morality of the character.

And then, of course, there is the most troubling deconstruction of Superman: the one in which the very goodness of his being is removed or compromised. The best example would be Superboy-Prime, an alternate Earth Clark Kent who helped save the world during the Crisis on Infinite Earths, and then became one of the most powerful and dangerous supervillains when he was manipulated by Alexander Luthor Jr. during the Infinite Crisis. In that event, something inside snaps, and Superboy-Prime lost all connection to the Superman he wanted to be – unlike Red Son Superman, no trace of a heroic goal remained – becoming a ruthless killer that took the lives of many heroes including Kon-El (Superboy). And in the current mythology, two versions of Kal-El are similarly broken: on Earth 1, Superman has been transforming into Doomsday ever since he defeated the creature and inhaled deadly spores in the aftermath; and on Earth 2, the original Superman has returned as a loyal general of Darkseid, assaulting the planet, its heroes, and even killing that world’s Jonathan Kent.

And then, of course, there is the most troubling deconstruction of Superman: the one in which the very goodness of his being is removed or compromised. The best example would be Superboy-Prime, an alternate Earth Clark Kent who helped save the world during the Crisis on Infinite Earths, and then became one of the most powerful and dangerous supervillains when he was manipulated by Alexander Luthor Jr. during the Infinite Crisis. In that event, something inside snaps, and Superboy-Prime lost all connection to the Superman he wanted to be – unlike Red Son Superman, no trace of a heroic goal remained – becoming a ruthless killer that took the lives of many heroes including Kon-El (Superboy). And in the current mythology, two versions of Kal-El are similarly broken: on Earth 1, Superman has been transforming into Doomsday ever since he defeated the creature and inhaled deadly spores in the aftermath; and on Earth 2, the original Superman has returned as a loyal general of Darkseid, assaulting the planet, its heroes, and even killing that world’s Jonathan Kent.

Which, of course, brings us back to Val-Zod.

His significance lies in his direct contradiction of the trajectory of Superman mythology over the past twenty years. He breaks the trend by actively reclaiming those aspects of the Superman mythos that have been lost, forgotten, or otherwise inverted. He is, first and foremost, someone with a profound faith in the goodness of others. This is especially notable when one remembers that his life is defined by moments that should have shattered this faith: his parents’ political imprisonment, his capture and detainment on Earth. In fact, almost all he has known in his life has been proof that people are selfish, cruel, and corrupt, but the world view he carries is the one he gained from his adopted parents – one of hope – and despite the overwhelmingly negative average of his life experience, his hope has not been dashed. He still believes in peaceful resolution over violence, and good over bad.

That is not to say that Val-Zod does not see the bad around him. Nor does it mean that the past twenty years of Superman mythos have denied that the character is a symbol of hope. All-Star Superman is a particularly classic interpretation of the character, but again, its focus is on Superman’s ultimate sacrifice. If the only means through which the mythology can show Superman as that symbol is by removing all or part of him, then we only experience the absence of hope, rather than its presence. This is an inherently negative act and therefore completely antithetical to Superman. Val-Zod, by contrast, is defined by his hope and empowered by it. The yellow sun may be the physical mechanism through which he is able to perform heroic deeds, but his morality, his philosophy, and his inherent goodness are what make him a hero.

It is especially appropriate that he is a Zod. In the context of Earth 2, it is interesting to see the roles reversed, with Kal-El representing the tyrannical, invading military power while Val-Zod fights on behalf of freedom. But in the wider mythological context, the metaphorical message is clear: the time for deconstructing the Man of Steel is over. Hope is the symbol of the House of El, but for the past twenty years the mythology has eroded away at that foundational aspect of Kal-El. Superman’s long identity crisis is nearly finished, and the reconstruction of his mythology is owed to Val-Zod. He embodies the best of what the Superman mythos should be, making him more than worthy successor to the House of El.

This article was originally published on Modern Mythologies.