Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie fire up the intriguing first chapter of a poptastic supernatural thriller that offers a psychic throwback to the glory days of Vertigo.

It seems fitting that Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie’s eagerly awaited new series has made its debut almost exactly 20 years after The Invisibles (by Grant Morrison et al). Because while the 2014 iteration is very much a signature McGillvie piece of work, it marks a fresh generation’s take on a similar mythical framework.

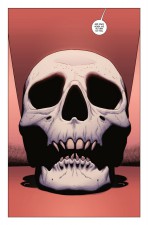

Interestingly, the notions of recurrence and reiteration are central to both series, established clearly in their opening words. The jazz-age flashback that launches The Wicked and the Divine opens with an emphatic reminder of the skull beneath the skin and the refrain “And once again, we return to this”. The words echo Elfayed’s “And so we return to begin again” at the start of The Invisibles, but very much mark the end of a cycle rather than the beginning.

Both series also draw their energy from a collision of the mundane and contemporary with the cosmic and eternal, leading us into their worlds through the explorations of a young adult trapped in the confines of a British city. So while disaffected scouser Dane McGowan was our way into the world of The Invisibles, this time round it’s Laura, a 17-year-old South Londoner whose passion for singer Amaterasu pulls her into a world of deep supernatural threat (and whose unblinking gaze challenges us from the comic’s elegant front cover).

It turns out that Amaterasu is more than just a vogueish chantoozie. She also claims to be the reincarnation of the Shinto deity whose name she bears, brought back to earth as part of The Recurrence: every 90 years, 12 gods return to the flesh for a glorious but terminal two-year burst.

They live fast, die young and – as Jamie McKelvie is drawing them – almost certainly leave a good-looking corpse. And, as this opening issue takes shape, it becomes clear that someone is keen to shave a bit off even that abbreviated life span.

Not everyone swallows this schtick, of course, and scepticism is given a voice here in the form of a journalist keen to debunk the claims of the emerging young ‘deities’. (Intriguingly, the journalist is named Cassandra, after the prophetess who was cursed to be always right but never believed).

Not everyone swallows this schtick, of course, and scepticism is given a voice here in the form of a journalist keen to debunk the claims of the emerging young ‘deities’. (Intriguingly, the journalist is named Cassandra, after the prophetess who was cursed to be always right but never believed).

At this stage, not much probably needs to be said about the craft of Gillen and McKelvie; as you’d expect from a sympatico creative team who have produced so many pages together, these pages ring with the clarity of a crystal champagne glass.

Their mode of storytelling finds perfect expression in McKelvie’s clean precision, and any questions you’re left with are the ones you’re supposed to be asking: who’s ‘Curtain Face’ in the prologue, who seems to be outside the circle of Gods? Whose was the damaged skull on the round table, and what left it like that? And who – or what – is the bigger threat targeting the young female deities (and catching Laura in the crossfire)?

The ‘gods as pop stars/pop stars as gods’ idiom (recalling John Lennon’s appearance as a psychedelic deity in The Invisibles) allows Gillen and McKelvie to take one of comics’ apparent weaknesses – the difficulty of depicting music – and turn it to their advantage.

Rather than having something specific in our ears, Amaterasu’s glossollalic warbling instead becomes something limited in its other-wordly beauty only by the reader’s imagination. Keatsy hit the nail on the head when he scribbled down “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard/Are sweeter” (Ode on a Grecian Urn, innit.)

The concert sequence captures that sense of being utterly immersed in a performance, as either artist or audience, as well as the intensity of the relationship that gives you an adrenaline rush when you think your hero might have noticed you – ramped up exponentially in this case by the purported presence of ‘godhood’. (And colourist/’lighting director’ Matt Wilson deserves a particular nod here, for his evocation of Amaterasu’s mesmerising performance.)

As much as its high concept, strong character choices are at the heart of The Wicked and the Divine. Laura doesn’t have the standard door-slamming YOU JUST DON’T UNDERSTAND bawling match with a pair of 2D pipe-and-slippers parents before storming off into the night. Instead, in a pleasing character beat, her concern is that they would understand. But Laura’s ‘worship’ of Amaterasu is something she very much wants to retain possession of. She wants it to be ‘hers’.

Meanwhile, Lucifer (Luci), the naturally combustible young woman who becomes Laura’s conduit into the world of the gods, starts off as a tiresomely precocious Skins kid, almost Ellis-esque in her shotgun banter. However, at the book’s explosive conclusion, when it becomes apparent that she’s far from running the show, she seems convincingly confused and frightened. With her earlier cockiness in the witness box she was reminiscent of Sting as the Ace Face in Quadrophenia – and we all know what happened to him.

Even at this early stage, we see fractal suggestions of themes and motifs that are likely to scale up as the series expands. In another reflection of The Invisibles, it’s clear that identity is going to be central to The Wicked and the Divine, embodied in Laura’s toilet transformation of herself from suburban face-in-the-crowd to Fabulous Creature – a mythic metamorphosis that has been at the heart of the pop experience at least since a David, two Micks and a Trevor togged up to become Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. At 17, Laura is stepping over the threshold into adulthood. She’s at the age where we frantically try to define ourselves, pecking like a magpie at the pop culture sparkles around us to construct an exopersonality to wear into the world.

From the emphatic image of the opening page onwards, the question of mortality is another part of the book’s tapestry: its key tag line has been, “Just because you’re immortal doesn’t mean you’re going to live forever”. Does being a teenager with a two-year lifespan mean that you’re suddenly faced with a life without consequences? What would that death sentence do to your sense of urgency – your need to change the world and leave something of yourself behind?

The inevitable 21st-century issue of celebrity is also brought up: the back cover of the book cites Laura as wanting everything that (presumably) Amaterasu and her peers have: maybe she should be a bit more careful what she wishes for.

One gets the sense that Gillen and McKelvie are positioning The Wicked and the Divine to be their defining work, and this clear, confident opening pulls back the curtain on a fictional universe of huge potential. They clearly know their readers well, and the initial response to the book indicates that they’re hitting the sweet spot.

Kieron Gillen (W), Jamie McKelvie (A) • Image Comics, $3.50, June 18, 2014