It’s interesting to consider that one of the most popular versions of Tōno Monogatari, Japan’s supernatural literary classic, was born because of one man’s desire to protect his country’s cultural heritage from the onslaught of modernization.

Kunio Yanagita was a government bureaucrat who spent his free time collecting native folklore, or minzokugaku. He often collaborated with a man called Kizen Sasaki, whom some refer to as the Japanese Grimm for the role he played in unearthing local folktales and customs. Together, they accumulated and published an impressive collection of myths, legends, and information about vanishing ways of life that continue to inform aspects of Japan’s history. Without them, bookshelves holding world literature would undoubtedly be poorer.

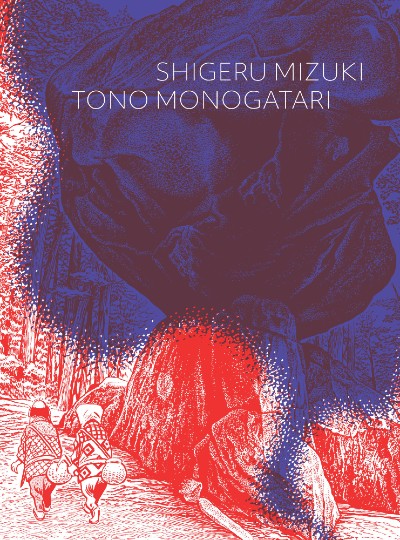

The legendary Shigeru Mizuki began working on his version of Tōno Monogatari a century after Yanagita’s collection appeared, eventually publishing it in 2010. It was commissioned by the city of Tōno, but Mizuki had long been familiar with the stories, as were most children who grew up as he did in Japan’s small towns and cities. As Zack Davisson points out in his introduction to this graphic novel created after Mizuki retired, the artist had been raised on tales of yokai, or spirits, by his grandmother. Their influence is palpable in much of his work — indeed, Kitaro, his famous one-eyed monster, wouldn’t feel out of place in these pages — where the lines between our world and the spirit realm blur easily and often.

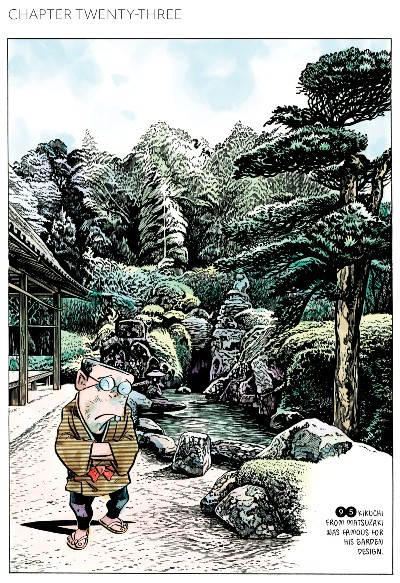

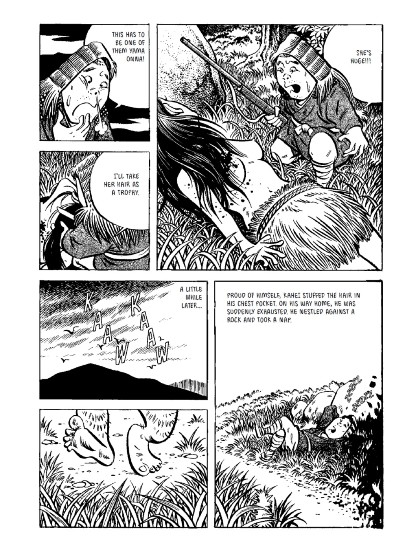

The Japanese spirit world is an undeniably vibrant place, teeming with ghosts, spirits, and sprites of all kinds. A number of these popular yōkai appear in the Tōno Monogatari stories, from amphibious kappa — almost human, with webbed limbs and a carapace on their backs — to humorous zashiki-warashi who traditionally haunt parlours or storage rooms and spend their time pranking humans. Into this universe steps Mizuki himself, now an old man walking through Tōno, introducing us to mythical beasts while trying to follow in Yanagita’s footsteps.

Several stories that appear here seem almost familiar, not because of the material itself, or the spirits who animate them, but because of how they tap into something universal. Like fairy tales the world over, they are also passed down from parents to (presumably older) children, changing ever so slightly with every retelling while retaining a sense of what Yanagita and Sasaki must have encountered when they set upon their quest. Mizuki’s tales, like the originals, follow no discernible order, running from one to the next without the semblance of an overarching structure. The aim, one suspects, is to capture the essence of the whole work. Some chapters also open in gorgeous colour, yielding another perspective on how Mizuki may have envisioned his fictional world.

He ends his tale in the twenty-ninth chapter by walking into Yanagita’s house and meeting his daughter-in-law before being confronted by Yanagita himself. The two chroniclers then have a short conversation about reincarnation, making for an ending as surreal as its beginning.

Davisson tells us that Yanagita dedicated his original work to people living in foreign countries, referring to friends who were leaving Japan and would like to be reminded of home. From the first English translation in 1975 to the Japanese graphic edition, and the English edition now in stores, these legends have continued to enthral all who encounter them. I can’t wait to see how coming generations interpret them in new, exciting ways.

Shigeru Mizuki (W/A), Zack Davisson (T) • Drawn & Quarterly, $29.95 CAD/$24.95 USD

Review by Lindsay Pereira