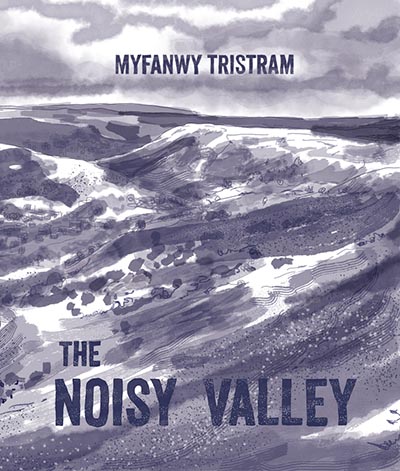

Simon Russell begins a series of articles today looking at upcoming projects that are still in progress and speaking to the voices behind them. He starts today with a focus on Myfanwy Tristram’s The Noisy Valley.

The Noisy Valley is a work-in-progress by Myfanwy Tristram in collaboration with The Workers Gallery – you can read about the genesis of the project here.

“True stories of protest from the Rhondda Valley,” indeed. Rhondda translates (clumsily) as ‘noisy’ and this region of Wales boasts a long history of protest in many forms. It’s no surprise that Tristram found a wealth of material to illustrate.

“I should think there isn’t a person in the area who hasn’t got either memories or direct experience of protest… I came away with enough for a full-length book.”

We are familiar with the growing body of comics reportage, reflecting current affairs (such as Olivier Kugler) and a long backlist of graphic novels about historic events and biographies (from Maus to Red Rosa), but The Noisy Valley concentrates on the slightly less familiar ground of personal retrospectives. Ordinary people remembering stories they lived through or watched their family experience. In many ways the project sits as comfortably with the sort of books Fantagraphics put out in the ’90s – like Real Stuff or Duplex Planet – as it does with modern comics-as-journalism. It’s nice to see this neglected space getting some love again.

In a long-form project, advancing incrementally in stolen moments between family and work, it’s inevitable that things will be revised and more connective tissue will grow between vignettes as the final stages are completed and things pull together. But there are already strong indicators that this will be a coherent piece, told with an attention to the comics form that many ‘serious graphic novels’ tend to eschew.

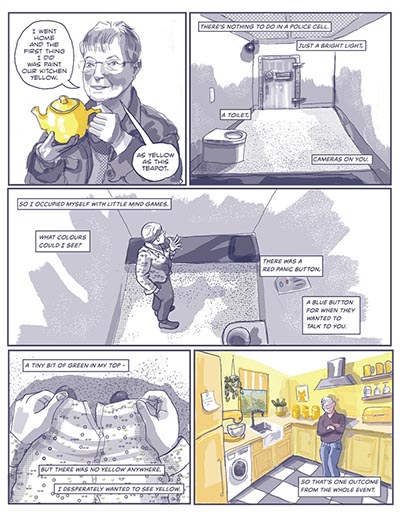

Each reminiscence begins with a picture of its protagonist, grounding the following pages in their voice over the artist’s and giving us an instant clue to their personality and physical presence. Where prose would spend time setting the scene and giving us the person to care about, Tristram is using the tools of comics to get straight to the point – “Hello,” and off we go!

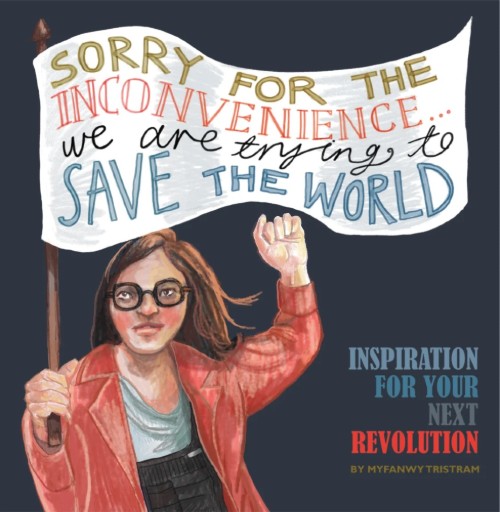

Visually, it’s easy to see that this is the same artist who drew the recent Sorry for the Inconvenience, We Are Trying to Save the World (also reviewed here at BF), but the more sequential structure employed here gives it a greater substance. The drawings lean more to illustration than cartooning – with crowds and portraits, witty signs and convincing wardrobes, Tristram develops a sense of naturalistic authenticity and detail, but manages to avoid the overwhelming specificity of super realism. So the images, like the words, can be combined and rearranged for a story that feels true.

A judicious use of colour accents among monochrome washes keeps the eye engaged on the page and runs some narrative threads throughout the book.

Tristram says she deliberately chooses to draw things comic artists usually shy away from – crowds; bicycles; horses – and you can see why, when she pulls them off with such casual ease. Much of this is referenced from archives and photographs, so I was expecting a stilted, frozen comic, but there’s none of that in evidence. The artwork is pretty smooth and consistent throughout.

Given time and Google, one might be able to identify many of the original photographs, but the alchemy of comics transforms them into part and parcel of the narrative. The act of drawing a scene familiar from news reports encourages us to look at the moment again… what we knew by osmosis is reframed and we see the people in the story, for a more intimate connection than the Grand Sweep of History that photographs present.

It’s in ‘David’s Story’ that the use of reference images among comics is most challenging – talking about an award-winning photojournalist puts a lot of pressure on the images to stay close to the recognisable source material, but Tristram sticks a balance between redrawing his photos and making the pages her own. Observing David from above, with his prints spread before him is a simple bridge between the two worlds – and having a Krigstein-like sequence of three panels overlapping that scene reminds us that the comic is the thing.

Page 7 is built on three of David’s archive photos, but only two are depicted as prints. The third is a transition between the captured moment and the memory itself, with all the action taking place in front of the photographer, who the comic places in the scene he is witnessing, with the reader further back still looking on him looking on. The page is then tied together and spun 180 degrees by a final panel of current-David talking directly to the reader. He’s leaning past his own panel border in to the scene of his memory – not so much recounting the past as reliving it.

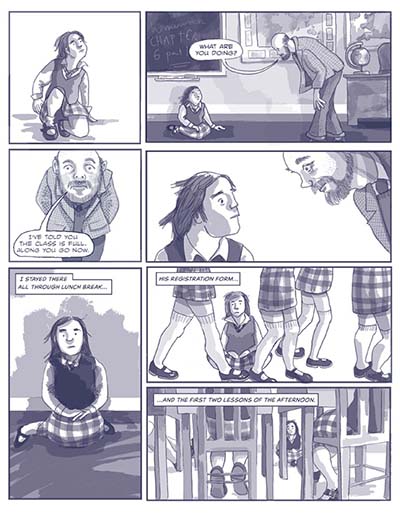

Elsewhere, Tristram plays with space and symbols to layer moments and actions in a specifically comicky manner. Page 2 of ‘Maria’s Story’ employs the multitrack nature of comics to great effect: the way the two figures are align in panels two and four as the teacher (and the reader) moves closer to the vulnerable child closes the physical space while maintaining the relationships. Time is compressed and extended in a way that makes the power dynamics of the scene very clear, and causes us to hold our breath at the standoff between to two characters.

The final two panels on the page manage to convert the passage of time with legs rushing past a static protagonist, but also use the verticals of those legs to foreshadow the chair legs hemming her in in the next panel… two sets of bars speaking to her of being a prisoner of circumstance.

When Jenny recalls her experiences in a police cell, and how its blandness provoked a desire for colour, Tristram ‘paints’ the walls roughly – as if interrupted half way through redecorating with a roller. It’s a subtle peek at the psychology of the narrator, but it also appears on a page with one of the few moments of show AND tell that Tristram succumbs to (being a WIP, the following may already have been considered by the author). Of the 42 pages submitted for preview, it is just in this first panel that Tristram’s faith in her own comicking looks to waiver slightly… Jenny holds up a yellow teapot while telling us the teapot is yellow. It reads like a verbatim transcript of the interviewee’s words, butin a monochrome comic, our attention has already been drawn to that yellowness by dint of it … uh … being yellow.

With The Noisy Valley, Tristram has expanded her comics vocabulary and refined her cartooning, to degree that we can be confident that the work will be excellently told. All that remains to be seen is what effects the editing and knitting together of this book’s disparate parts has on the whole. I’m willing to bet it will result in something that bears repeat readings.

POSTSCRIPT

I sat down over coffee with Myfanwy to chat about The Noisy Valley. Appropriately for a project about storytelling, we talked in circles and tangents and found ourselves digressing and coming back on topic, so what follows has been edited for relevance and reordered for clarity.

I had shown the review to Myf in advance in case she had any issue with my reading of her work, or if I was revealing too much for a work-in-progress. The only objection she raised was where I say she has a facility for drawing difficult subjects – that is, she insists, an illusion hiding some serious effort and reworking.

Perhaps that illusion is all the reality we readers need, but it would be wrong to gloss over the blood, sweat and Ctrl+Z required for it to read so convincingly.

The Workers Gallery on Small Press Day

MYFANWY TRISTRAM: Workers Gallery hosted an exhibition of pictures from my protest book – they’re a little community hub that also operates as a shop, a library, a meeting place etc. (they opened up as one of those warm centres last winter) and Gayle and Chris invited me down to give a talk, a workshop… whatever.

I said I’ll do a zine where I collect local memories of protest. I thought I would set up a Google form everybody could like just type in their responses. But Gayle was, like: okay, well first of all, not everybody in this area has the internet. And second of all, you’ll get better results if you come and talk to people.

The Workers Gallery is so community-focussed, that they basically know everybody in the village and beyond. So people would pop by, “Just delivering the milk, but I thought I’d see what’s up at the gallery”. And before you knew it, Gayle would be getting them to sit down and talk to me.

I’m still thinking, make it quick – I don’t want this to take the rest of my life having just put my big project, Satin & Tat, aside because it was too big for just now. So I wanted this to be quick and dirty. But when I looked at the material… I’ve got to do this proper justice.

This is often how I trick myself into doing something! When I used to go running, the only way I could get myself out the door is to tell myself it doesn’t matter. You don’t have to run really fast. You don’t have to run really far. Just go and do anything… anything at all. And I think that is how I approach anything that’s a bit daunting – let’s just start with no pressure and see what happens.

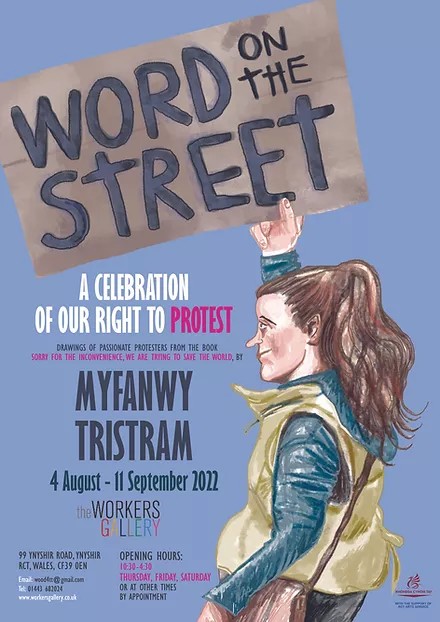

Sorry for the Inconvenience… We Are Trying to Save the World – previous work from Myfanwy Tristram

SIMON RUSSELL: So, when yo -u went into conducting interviews in person face-to-face… a lot of the people just walked in to the gallery? They were not prepared, they just turned up?

TRISTRAM: A couple of people did come up immediately after my talk. There’s a short story about a Labour banner that has a cross stitch on it. Clair ran out to the boot of her car and pulled it out to show me there and then! But other people I sort of met and exchanged email addresses with and set up interviews.

The gallery has had a long relationship with David Hurn, a Magnum photographer, who recorded the aftermath of the Aberfan disaster where the mountains slid onto a primary school and killed a number of children. Not a lovely subject matter, but important, and used in the court cases afterwards as evidence. David’s known for photographing Brigitte Bardot and The Beatles and James Bond – quite a big name in his field. Gayle told me about his long and prestigious career, so I was almost nervous to go and talk to him, but he was so personable and had a lot to say about everything and anything. Everything he said was a gem, but I had to remember when I was editing it to stay on the topic of protest!

RUSSELL: You recorded the interviews in person and transcribed them before drawing the comics. How much of the interview did you keep? How much did you edit or elide?

TRISTRAM: In almost every case, it was edited. They were usually long conversations, so I had reams of stuff, but I haven’t changed the words unless some phrasing was a bit awkward – where I knew what they meant to say but they didn’t quite put it clearly. There’s no point in trying to do a comic that depicts a 45 minute conversation with every word included. You have to just pick and choose the thread that you’re going to follow.

I sent everyone their script for approval. One of the first strips I worked on came back with a few corrections after I’d finished drawing, so from then on I got approval before drawing the pages!

I try to take photos of people when I interviewed them, but there’s never enough, so often, I look at their Twitter and Instagram, thinking if they shared it on social media, they must be happy with how they look in this photo – so let’s work from that.

Something I found a lot of fun was when somebody would say, “Oh, we marched through the streets of Tonypandy,” and me not knowing what the streets of Tonypandy look like but having Google Images and Google Streetview.

A lot of this memories are from the ’60s or ’70s or ’80s, so I enjoyed looking at what people were wearing. You can draw a march from your imagination, but it’s only when you look at the photos that you see, my God things have really changed!

Word on the Street – Myfanwy Tristram’s exhibition at the Workers Gallery

RUSSELL: So, you’ve got photographs, you’ve got interviews. And you’ve got your visual research. How do you pull that together to turn it into a coherent comic?

TRISTRAM: I thumbnail really roughly with pencil crayon on paper. And then (I don’t think this is necessary… I don’t know why I don’t just go straight to digital, but) I pencil each panel on paper but not always on the same sheet for each page. Working digitally, I can just resize stuff, so I’ll just draw it as big as I want and then I assemble the page in Affinity. Just paste each picture in the right place and then draw the borders around as they fit in with the font dialogue in and then draw digitally on top.

RUSELL: So the pencils are completely lost in the end?

TRISTRAM: There’s a layer in between. So there’s the drawing and all the words and then there’s a layer under that which I just filled with white. So you know in theory, the drawings are still underneath there but it’s like a digital drawing or painting on the finished page.

RUSSELL: In terms of practicalities, this is an English language book about a Welsh community. Are you doing the lettering in a way that it could be easily translated?

TRISTRAM: It’s all on its own layer, or layers, I used a font rather than hand lettering, so that would be a pretty straightforward thing for a Welsh publisher to adapt.

RUSSELL: People in The Noisy Valley have a lot of stories… their interactions with protests fold back into their own stories and how they think of themselves.

TRISTRAM: Everyone’s life is intertwined with everything else that they do. I usually approach stuff by trying to think of my own experiences. How did I feel about it? Is there a story there? And I think that’s the kind of story I like telling really is personal experiences. it’s much more interesting to hear about the little day to day experiences of miners’ families than to read about what Margaret Thatcher did in Parliament. It’s all part of the same story, but I’m most interested in the little details that could get lost.

RUSSELL: Are you planning to include footnotes in the book about the context or the results of the different protests?

TRISTRAM: No, I don’t think so. I think largely they are just embedded in the stories themselves. So when people tell you a story about something that happened it sort of finishes off quite nicely – people came together and they made a change. Or didn’t. I think people sort of wrap it up for themselves.

RUSSELL: How is The Noisy Valley going to come out?

TRISTRAM: Watch this space? The Workers Gallery have been really, continually, supportive – sending me ideas for grants I could apply for and suggesting publishers that deal with Welsh books.

When I put in for Arts Council funding – because of course, it’s Arts Council England, it’s quite a hard sell. This is about Wales, but, it has universal application across the country.

To be honest, I’ve just sort of put aside all thought of where this is going, how are we going to get it out to people, for now because I’m just going to finish drawing it.

The Workers Gallery really wanted to amplify the voices of local people. And, you know, I don’t know if it’s true or not, but one of the things they said was just the act of an artist coming, paying attention and wanting to listen and depict these people was really validating in itself.

Visit Myfanwy Tristram’s site here

Article by Simon Russell