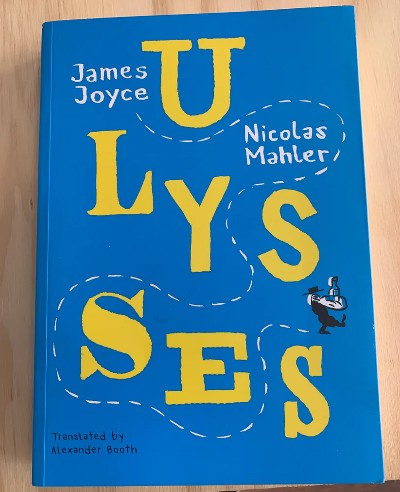

It takes a bold artist to reinterpret a classic work of literature, and a supremely confident one to choose Ulysses, what many refer to as “the greatest novel in the English language.” Austrian author and illustrator Nicolas Mahler is, by this measure, a supremely confident man.

To be fair, he has done it before, which may explain where that sense of confidence comes from. Consider his take on Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, for instance, where Mahler chooses to avoid the Madeleine incident entirely, without the need for an explanation. In Party Fun with Kant, he has the German philosopher visit an art exhibition with Hegel and go supermarket shopping with Nietzsche. Then there’s Alice in Sussex, where the rabbit hole is swapped for a house underground and a famous monster lying in wait at the end of that little girl’s journey. So, for him to swap Dublin with Vienna and Leopold Bloom with someone named Leopold Wurmb is entirely in keeping with some private tradition.

There are multiple reasons for the pedestal that Joyce’s classic rests upon, starting with how it brought the novel kicking and screaming into the modern world, rendering structure and form superfluous to expression. It may be known primarily for its stream-of-consciousness technique — mostly by those who haven’t read it — but there is also much to be said about its approach to characterisation, symbolism, and sex. What Joyce did, by reinterpreting Homer’s Odyssey, is elevate the quotidian into something heroic and extraordinary, taking the perfectly ordinary Leopold Bloom, his wife Molly, and a single day in June 1904, to allude to something larger and more timeless.

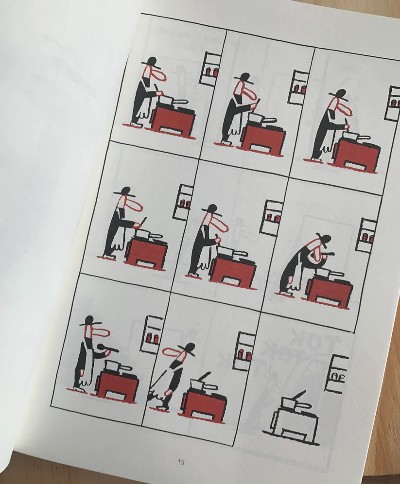

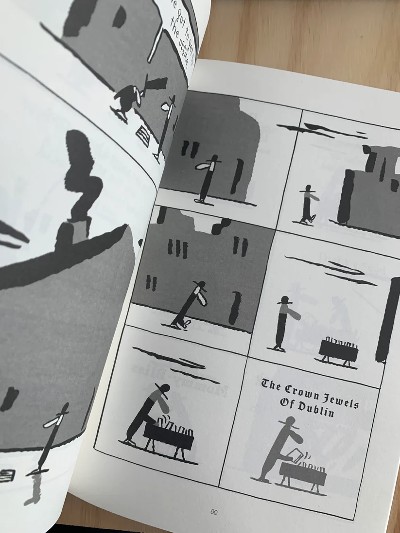

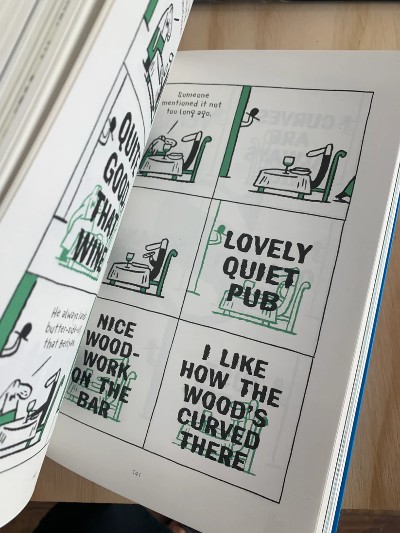

Looking at Mahler’s work reminds one of Occam’s razor, or the law of parsimony positing that, of two competing theories, the simpler explanation of an entity is to be preferred. It’s easy to imagine him looking at a dense paragraph written by Joyce, and meticulously stripping it of everything but its essence, before turning to a blank page and coming up with a visual to embody it. On one page, Leopold Wurmb walks past a blank space that simply features the words ‘House’, ‘blocks of flats’, and ‘Villa with neighbouring buildings’. On others, single words stand in for minor events. It starts to get disconcerting after a while, which is presumably the effect Joyce was going for too in some chapters such as his Proteus episode involving a dog urinating and his alter ego Stephen Dedalus thinking about life.

The question of whether one ought to be familiar with Joyce’s Ulysses is moot because not knowing Homer doesn’t get in the way of reading the Irish writer. What matters here is Mahler’s minimalism, juxtaposed against his surreal, exaggerated caricatures. It is also a bit of a wonder to consider what Joyce’s 265,222-word book is boiled down to.

Does it all work? No, not at all. Some of the humour doesn’t come through (newspaper advertisements in German, for example, aren’t explained by translator Alexander Booth), and the allusive art often misses the mark, presumably because the reader may not be equipped to do some heavy lifting. It’s still a powerful effort though, and any reinterpretation that tries to make us look at something from a new perspective ought to be celebrated. After all, isn’t that what Joyce probably set out to do in the first place?

Nicholas Mahler (W/A), Alexander Booth (Tr) • Seagull Books, $24.50/£17.99

Review by Lindsay Pereira