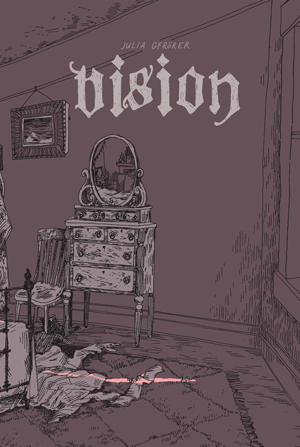

In Vision, Julia Gfrörer pulls the reader into her haunted house mystery and slams the door.

Julia Gfrörer’s disquieting and relevant new book from Fantagraphics sits very nicely with her two previous titles for the publisher (Black is the Color and Laid Waste). And when an artist has this kind of control over her material, she doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel with every book to remain compelling.

Taking place in a non-specific oldie-timey setting (with a flavour of Edwardian London), Vision rolls out the fate of Eleanor, a young woman pinned down by the full weight of the patriarchy. Males are a shadowy and overbearing presence in her life – even (or especially) the dead ones: she stems the bleeding from her self-harm with the black mourning handkerchief she carried for her father, and she has been left trapped in her situation because of the death of her fiancé at war.

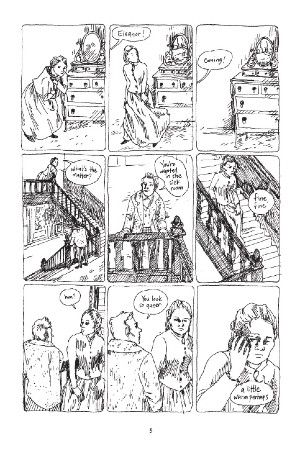

Eleanor’s loss leaves her at the whims of society’s harsh norms. Forced to live on the generosity of her drippy brother Robert, she becomes an unpaid and underappreciated nursemaid for his troubled wife, Cora, who veers between raging paranoia and demanding passive-aggressive lucidity.

In the privacy of her own room, though, Eleanor is subject to an altogether more elusive presence – an unseen entity that appears to dwell in her dressing-table mirror and appeals to more visceral urges that have to be suppressed elsewhere. But even the spirit in the mirror feels that it has possession of Eleanor. Although we’re invited to wonder to what extent it’s a figment of the young woman’s imagination, it flies into a fit of jealousy over Eleanor spending time with the family doctor (who is treating her glaucoma), leading to a crack erupting across its surface, a sulky silence and subsequent poltergeist activity.

The air of paralysis and stultifying enclosure is palpable throughout the book. The strictures of society and the loss of her fiancé have cut off Eleanor’s apparent escape routes, and even a venture through the looking glass reveals nothing like Alice’s Wonderland. Only in one beautiful sequence – showcasing the author’s gift for depicting the natural world – do we get a sense of release, as housemaid Beth reads a poem to the bedbound Cora. However, that glint of light only draws attention to the suffocating darkness that surrounds it.

That sense of confinement extends to the reader, as Gfrörer uses the subjectivity of comics to draw us deep into Eleanor’s experience. We soon become enmeshed in the sticky intricacy of her scratchy, urgent line – especially in the cell-like constraint imposed by the book’s tight nine-panel grid.

Even the book’s more objective sequences pin the reader down and make them squirm. One very uncomfortable sequence of penetrative eye treatment doesn’t require a lot of digging to reveal its subtext (and would have poor old Dr Wertham bouncing out of his grave and saying “I told you so!” about the old injury-to-the-eye motif).

Gfrörer pulls off a laudable trick in Vision, using a period drama and the trappings of the horror genre to draw parallels between the situation facing women then and now, without any flashing arrows or laboured analogies. The ending may prompt debate – as it was no doubt designed to do – but it highlights the author’s willingness to dodge pat answers and to make powerful use of generic conventions.

Julia Gfrörer (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books, $16.99

Buy online here from Fantagraphics or in the UK from our friends at Gosh! Comics here

Review by Tom Murphy

[…] • Tom Murphy reviews the disquieting confinement of Julia Gfrörer’s Vision. […]