Haunted by the ghosts of a war he never fought, documentary director Olivier Morel found himself deeply wounded by the psychological and spiritual demons brought home by vets of the Second Iraq War. His stirring behind-the-scenes graphic exorcism shines a much-needed spotlight on the plight of veterans marginalized by a society that is uninterested in their well-being once they are no longer able to fight.

The first thing French documentary director Olivier Morel did upon becoming a citizen of the United States of America was to begin development of a film that peeled back the veil on the deplorable state of veteran care for soldiers returning home from war. He would test his new home’s tolerance for self-examination and its fanatical adherence to the right of free speech straight out of the gate.

The first thing French documentary director Olivier Morel did upon becoming a citizen of the United States of America was to begin development of a film that peeled back the veil on the deplorable state of veteran care for soldiers returning home from war. He would test his new home’s tolerance for self-examination and its fanatical adherence to the right of free speech straight out of the gate.

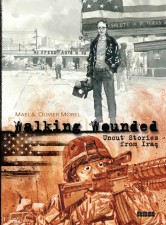

Widely lauded as a stark, unflinching indictment of America’s treatment of its battered and broken soldiers, Morel’s documentary On the Bridge told the stories of various military veterans, who returned home to discover just how expendable they really were. Emotionally traumatized by the filming of the documentary, Morel’s graphic memoir of the period adds an additional layer of insight to an already deep emotional well.

It’s a difficult account to read, though not for any reason related to quality or craft. Morel’s sensitivity to the spiritual and physical trauma experienced by his subjects leaves him emotionally drained, if not scarred – a burden he challenges his readers to bear as he draws them deeper into the claustrophobic despair suffocating his vets.

Despite being entirely filmed on American soil, Morel’s film was not without very real, very present danger to the vets telling their stories. The emotional toll on his subjects was steep and the potential for disaster great, as they resolutely dove into memories so spiritually repugnant they’d almost rather die than revisit them.

For the reader, this inherent risk of calamitous failure only exponentially increases the emotional tension permeating the book. It’s like probing an exposed nerve with your tongue – a jangly, electric, too-much coffee feeling that leaves you spent by the time you read the final panel. Morel’s jarring shifts back and forth through time only serve to destabilize his audience further.

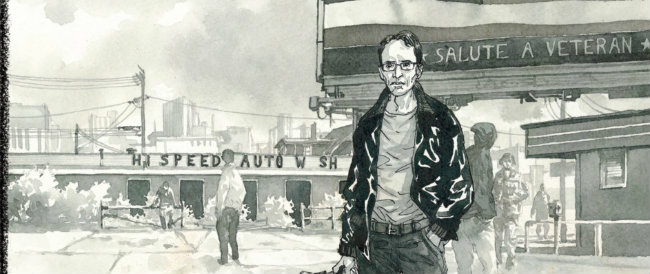

In collaborator Maël, Morel finds a superlative artistic match more than capable of translating this roiling emotional stew to the comics page. Jagged linework visually underscores the rawness of the psychic wounds afflicting the veterans whose experiences Morel records, their memories and his often blending together in disturbing, lurid sequences that border on the surreal.

Maël’s use of colour reinforces the intensity of the emotional conflicts captured by Morel’s camera. Moving from cold, muted greys in the director’s gloomy present to the hot, garish oranges and reds of sweltering desert combat in the past, the artist creates a balanced visual tone that resonates on both an emotional and aesthetic level.

Emotionally draining and intellectually challenging, Walking Wounded is a beautifully illustrated exercise in exorcism by way of graphic storytelling. Or perhaps that’s selling Morel too short. One suspects he doesn’t want to be rid of the sympathetic trauma he experienced while making his documentary. To do so would be to invalidate not only his own emotional journey but also those of the vets he connected with.

Rather, I think Walking Wounded is an attempt to gain perspective for Morel – an opportunity to scrub the emotional filters and place his journey in the proper context. For as harrowing and desperate as making his film was, it was nothing compared to the horrors of war experienced by his subjects – or the despair they felt upon returning home.

Olivier Morel (W), Maël (A) • NBM Publishing, $24.99

Make $100 Dollars | 100 Ways to Make $100

@ @ @ www . jobsrev . com @ @ @