Retroflect has a long history at Broken Frontier, having been both a series of blogs and an ongoing column here in the past. Today we return for the first time in two years to this infrequent feature for looking at pre-millennium comics, from celebrated classics to obscure and largely forgotten titles. Our subject this time is the forgotten DC horror anthology Wasteland which ran for 18 issues in the late ’80s. As ever, decades-old spoilers are contained below…

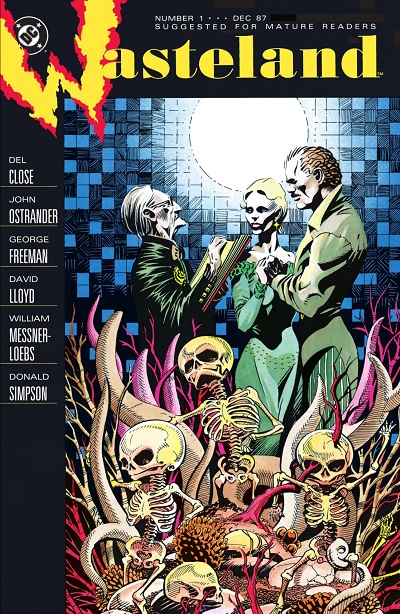

Published between 1987 and 1989, DC’s horror anthology series Wasteland is a largely forgotten publishing footnote now; one of those short-lived experimental series that populated the DC line of the ‘80s. Written by John Ostrander (Suicide Squad, Grimjack) and comedian/actor/teacher Del Close, it was illustrated by a rotating core of artists including David Lloyd, William Messner-Loebs, George Freeman, Don Simpson and Bill Wray, alongside a number of occasional guest creators.

To an extent “horror” seems an entirely unsatisfactory term to describe Wasteland. DC had, of course, published a large number of supernaturally themed “mystery” books in the ‘70s including such ghoulishly titled books as House of Mystery, Ghosts, House of Secrets, Unexpected, Weird War Tales, Doorway into Nightmare, Secrets of Haunted House and many more. But by the early part of the ’80s they had all but disappeared (with the short-lived Elvira’s House of Mystery being the exception). Wasteland was a very different entity though. Rather than the repetitive EC Comics-lite fare of its predecessors Wasteland was a far more cerebral affair; a collection of three bleakly satirical short stories each issue, with a throughline of dark social commentary.

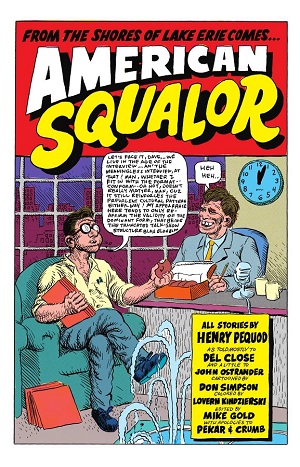

While content, theme and genre were eclectic, arguably even erratic, one constant was Del Close’s “semi-autobiographical” stories which ran in nearly every issue of the series. Delivered with an exaggerated anecdotal approach Close took events from his colourful life and embellished with a knowing but world-weary nod in the reader’s direction. Over the course of the eighteen issues of Wasteland Close’s endearingly rambling tales would see his fears of burning beds realised in the memorably Pekar-esque ‘American Squalor’ (with George Freeman adopting a Crumb-like style for the duration, above left); a meeting with the inventor of an anti-gravity machine (art by William Messner-Loebs, above right); Close picking up a ghost hitchhiker while on the road with his acting troupe; being there at birth of scientology with L. Ron Hubbard; and taking revenge with the aid of a witch’s spell. Many of these stories would end on a note stating something to the effect that they were “mostly” true.

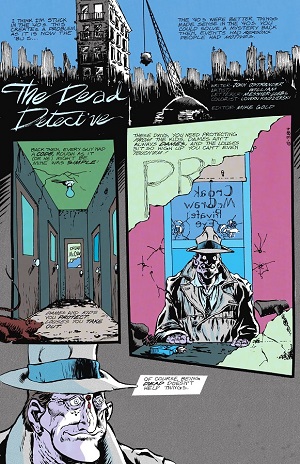

The only other “continuing” feature was the adventures of Croak McCraw. ‘The Dead Detective’, a deceased but conscious private investigator. Despite having been shot in the forehead other characters seemed oblivious of the expired nature of his still sentient corpse leading to a Gerber-ian series of misadventures where the “protagonist” is anything but. ‘The Dead Detective’ appeared in issues #8 (above left, art from Messner-Loebs), #12, and #17-18.

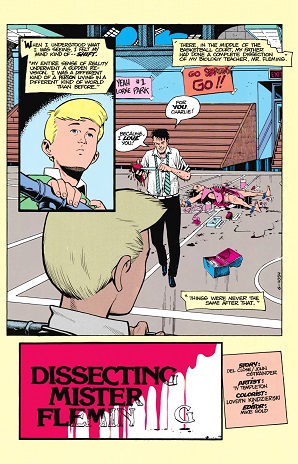

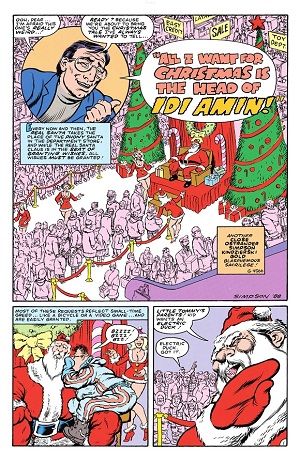

The premises of the other complete-in-one stories were as bizarre as they were varied: Genghis Khan body-swapped to contemporary times; a detective realising the Rapture is imminent; an elderly couple who wake up to find a giraffe living in the back yard in American suburbia; Lovecraft’s last days; a schoolboy discovering his father dissecting his biology teacher in the school gym (above right, illustrated by Ty Templeton); a primary school run as if it was an episode of Sesame Street; a child requesting the head of Idi Amin from Santa Claus for Christmas (below left, art by Donald Simpson); and many similarly unlikely narrative starting points. If there’s a weaker side to Wasteland it’s that sometimes an intriguing set-up failed to deliver on its promise but when they did hit the mark it was with a brutal and unforgiving accuracy.

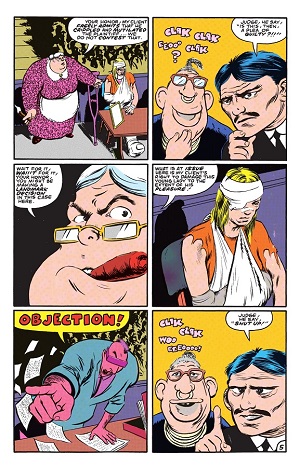

While Wasteland was entirely divorced from the DC Universe-proper there were infrequent nods in its direction, particularly In #5’s gloriously meta ‘Big Crossover Story’ featuring Close and Ostrander taking a meta journey through the super-hero world an illustrated by David Lloyd (above left). But it’s as a precursor to the Vertigo line that Wasteland most deserves to be remembered. Psychological, near nihilistic horror that, for the 1980s, pushed boundaries in a way that was years ahead of its time. Perhaps most memorably in Wasteland #4’s ‘Celebrity Rights’ (below left, art by Donald Simpson), a caustically cutting commentary on reality TV, celebrity culture, and social justice, wherein justice on a courtroom TV show is decided on terms of popularity rather than evidence.

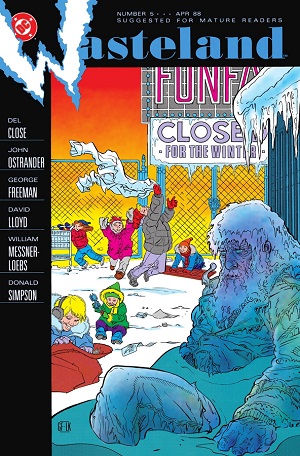

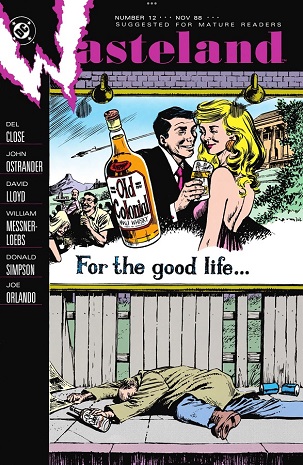

Each cover to Wasteland was unrelated to the stories inside, rather they told their own one-page story with the similarly themed covers to #5 (George Freeman) and #12 (David Lloyd). The wildly differing styles of the artistic line-up also reinforced the quirky but bleak tone of the book. Wasteland’s final issue was the only one to break the presentational structure of the title, with the Dead Detective taking a full-length meta trip through the stories of the previous seventeen issues ending up at the beginning of the first story from issue #1.

Five years ago a collection of Wasteland was announced by DC. It never materialised, although it’s still listed on Amazon UK with a publication date of January 2035! Wasteland is available within the ruins of ComiXology, although in an incomplete form with all issues with the exception of #6 listed. This is probably due to a printing error at the time when the cover to #6 was accidentally used for #5. The correctly printed #5 was then distributed to shops a week later with “The Real #6” printed with a blank cover the month after. Alternatively it could be because the Del Close autobio story in #6 has characters who use a number of racial slurs (within context). Either way it’s a frustrating omission, particularly as #6 is part of the only continuing story in the book’s run.

If you’ve never experienced Wasteland, though, it’s well worth investigating those digital issues. This forgotten gem of comics deserves far more recognition in the annals of horror comics. A mature readers book with a diverse but distinctive voice and one that should have been long celebrated as one of the finest comics DC published in the 1980s.

Article by Andy Oliver