Rachael Ball had already established her skill at weaving autobiographical experience into new narrative form in her previous graphic novel The Inflatable Woman a couple of years ago. There she combined magic realism and graphic medicine to tell the story of zookeeper Iris Pink-Percy and her quest for online love following a diagnosis of breast cancer. Wolf, her most recent book from SelfMadeHero, explores childhood grief and the early loss of a parent. You can read more about how Ball channelled the events of her own younger years into Wolf in this extensive interview with her by our own Jenny Robins here at Broken Frontier.

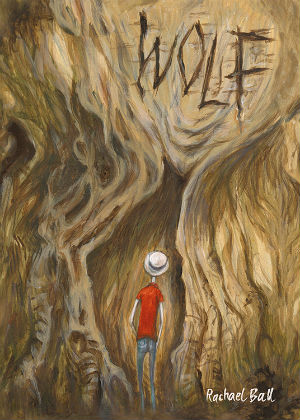

Rachael Ball had already established her skill at weaving autobiographical experience into new narrative form in her previous graphic novel The Inflatable Woman a couple of years ago. There she combined magic realism and graphic medicine to tell the story of zookeeper Iris Pink-Percy and her quest for online love following a diagnosis of breast cancer. Wolf, her most recent book from SelfMadeHero, explores childhood grief and the early loss of a parent. You can read more about how Ball channelled the events of her own younger years into Wolf in this extensive interview with her by our own Jenny Robins here at Broken Frontier.

Set in the 1970s, Wolf opens with a sequence where our protagonist, the young Hugo, is immersed in the company of his father in that way that only children can be; it’s part hero worship, part showing off and part rapt fascination as the two explore woodlands together. While there’s something quite joyous in this sequence there are also ominous portents hidden in plain sight in their seemingly carefree adventures. For Eric is soon to lose his father; an event that will see him, his mother and his siblings displaced and beginning a new life in a new family home.

Set in the 1970s, Wolf opens with a sequence where our protagonist, the young Hugo, is immersed in the company of his father in that way that only children can be; it’s part hero worship, part showing off and part rapt fascination as the two explore woodlands together. While there’s something quite joyous in this sequence there are also ominous portents hidden in plain sight in their seemingly carefree adventures. For Eric is soon to lose his father; an event that will see him, his mother and his siblings displaced and beginning a new life in a new family home.

Over the course of the next summer Hugo and his brother and sister Eric and Sonia, get to know local lad Icky and learn of their mysterious and apparently monstrous next-door-neighbour the “Wolfman”. They also find themselves inspired by the film The Time Machine to build their own time-travel device (one which looks remarkably similar to a go-cart) in order to go back to the past and find Hugo’s father again. But the one missing part of their chronology-defying contraption can only be found in the strange Wolfman’s home, leading to an encounter that will have profound ramifications for everyone concerned…

To describe Wolf as a memoir (albeit one told through a fictional avatar) examining grief and family would obviously not be an inaccurate statement but it seems insufficient in detailing the entirety of what Ball communicates in these pages. This is a book that is about the spaces left behind in loss; the less obvious ways that grief manifests itself in the young; and the elaborate coping mechanisms that children like Hugo adopt to deal with that hole in their lives. And permeating its pages is the almost deafening silence of an awkward, suppressed sorrow that acts almost as an extra character in its own right.

Ball’s work is always impressive in the manner in which she avoids undue exposition and ensures foremost that the reader experiences her characters’ feelings through their visual characterisation (evident from the very beginning in her depiction of Hugo and his father). The loose pencils give her pages an added authenticity and the cast an emotional integrity that is all the more human for their exaggerated physicality. Like The Inflatable Woman, Wolf too is a brick of a book in format but that allows Ball the opportunity to open up the carefully paced flow of her pages and allows certain key sequences the chance to breathe. Her bleak but poignant use of visual metaphor and her evocation of a child’s eye view of the world is overt yet subtle throughout, culminating in a quite beautiful moment regarding Hugo’s father’s hat – a recurring motif throughout – that is deeply eloquent in its quiet understatement.

On one hand Wolf speaks of the universality of an inevitable rite of passage but it is nevertheless careful to underline how unique that process is to each individual who lives it. A book of parallels Wolf talks to us of both fragility and resilience; of the stark realities of bereavement framed through the dual lenses of the everyday and the outlandishly imaginative. It’s Rachael Ball’s finest achievement in comics to date and an outstanding book in what was a very strong 2018 for SelfMadeHero.

Rachael Ball (W/A) • SelfMadeHero, £15.99

Review by Andy Oliver