BROKEN FRONTIER AT 20! Championing the medium, exploring its full potential, and analysing its unique storytelling tools are all part and parcel of the Broken Frontier ethos. There’s no one in comics, though, who articulates their love of the possibilities of sequential art quite like Woodrow Phoenix. A pillar of the British indie scene, Woodrow’s work on projects like Nelson, Rumble Strip and She Lives constantly interrogates the form and embraces its distinct properties. I’ve known Woodrow for many years, sat on panels with him, and worked with him as a fellow judge on the Myriad First Graphic Novel Competition but today’s interview is, surprisingly, the first time we’ve officially chatted at BF. As we celebrate 20 years of Broken Frontier it’s a delight, then, to be able to run what I genuinely think is one of the most interesting interviews we’ve ever published!

ANDY OLIVER: Anyone who has listened to you at events speaking passionately about the possibilities of comics will know how inspiring your love of the form is. Indeed so much of your own work seems to be about constantly finding new ways to exploit their potential. So let’s start by asking you what you feel are some of the truly unique narrative qualities of the medium – the things that only comics can do – and why they are so effective at connecting with readers?

ANDY OLIVER: Anyone who has listened to you at events speaking passionately about the possibilities of comics will know how inspiring your love of the form is. Indeed so much of your own work seems to be about constantly finding new ways to exploit their potential. So let’s start by asking you what you feel are some of the truly unique narrative qualities of the medium – the things that only comics can do – and why they are so effective at connecting with readers?

WOODROW PHOENIX: The thing that fascinated me about comics as a child is the thing that still fascinates me, and that is the way a strip exists inside and outside time. An image, when it’s part of a succession of images, is moving and still at the same time. So you can look at a sequence for as long as you want, you can read a story backwards, you can jump forwards, but each panel remains fixed. You can possess them and inhabit the moments they present in a way that you can’t with film or tv. Comics give the reader control and agency that is not possible in other media. I think that’s why kids get obsessed with them.

Plus the way that format can completely change how a story looks and feels is the biggest quality other media don’t have. You can really do a lot with differences in the height and width of the page, the quality of the paper, colour and how it’s applied, the shape of panels, even with the width of gaps between panels and the thickness of panel borders or lack of them. Every single element of the comics page has to be placed there by a human hand so the results can be as varied as the humans who make them. I could go on about these things all day, as you know! But shall we move on?

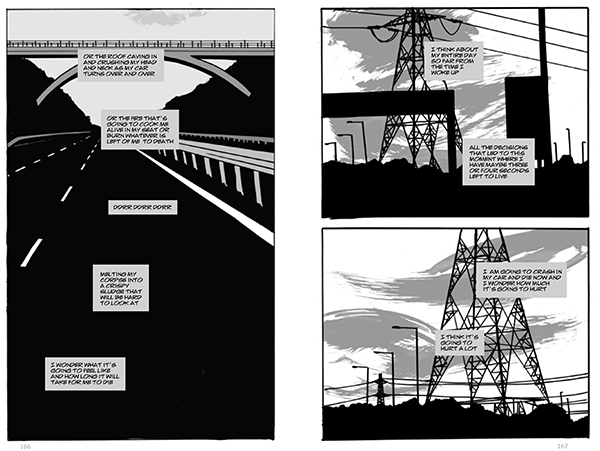

AO: One of your most important works Rumble Strip from Myriad was recently re-released with new content as Crash Course from Street Noise Books. It’s an uncompromising commentary on our relationship with cars and the damage they can cause. What was the catalyst for wanting to bring that story to the page and can you tell us a little about the way in which the book’s distinctive visual perspective forces the reader to place themselves within its pages?

PHOENIX: I was 13 when my younger sister was killed in a car crash. My family was never the same after her death. It was–and still is–unbelievable something so utterly devastating could happen so easily. To thousands of people every day. Once you experience how compromised our built environment is, how unprotected we are by the infrastructure around us, how convenience for some people means danger for everyone else, it’s hard not to notice it all the time.

So you can see that when I made Rumble Strip this stuff had been on my mind for a long time. But I couldn’t do it until I found an approach that got people to understand the problem on a visceral level. Without that it would just be stats and lists. Eliminating characters and making the reader into the protagonist was a big gamble because nobody was sure it would work but my editor trusted me enough to try it. I’m happy with the results. It’s not easy to explain but all you have to do is read a few pages and you get it instantly. That mixture of simple viewpoint and complex identification is something that’s only possible to do in comics. I think if I had to sum it up in one sentence, my job as a creator is to show you something you may have been completely unaware of and make you care about it. So there’s an immediacy and an intimacy to my talking to you through a picture in your hand that makes it personal. And that’s why it works.

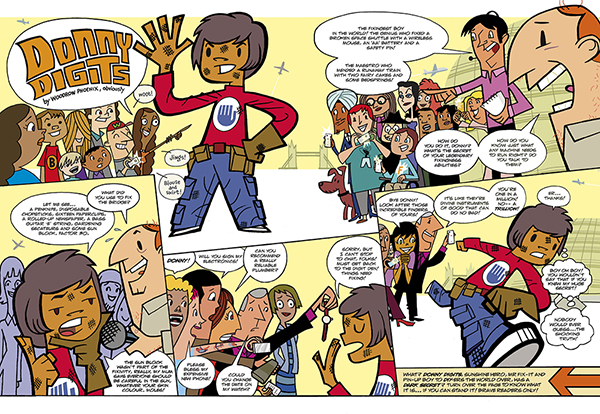

AO: Building a younger readership for comics is something that is constantly being discussed as a traditional audience for serial comics gets ever older. Your all-ages Donny Digits strips were recently collected by children’s publisher Bog Eyed Books. What’s the premise of Donny Digits and how did you approach employing the structure of the page to appeal to the imagination of the younger reader?

PHOENIX: Donny Digits was pretty much a laundry list of all the things I noticed children love when I do storytelling sessions: simple premise, ridiculous villains and lots of jeopardy. Donny’s a hero who can fix anything, his twin brother is a menace who breaks everything and crooks can’t tell them apart. I realised I could use the 3-page format of the Guardian weekly comic to open each episode with a standard intro page and then give readers a big visual jolt when they turned over to see a double-page splash, so I designed it with that in mind, making each spread graphically exciting with acid colours, big sound effects and lots of diagonal panels. Plus terrible puns and other jokes. It uses the big surface area of a newspaper that opens flat for maximum impact. I tried as much as possible to have something dramatic or layered happening on those spreads so there was a lot for children to look at and they liked that. This approach doesn’t work so well in a bound volume where images disappear into the centre binding, so the book collection isn’t quite as exciting visually… but don’t tell anyone I said that!

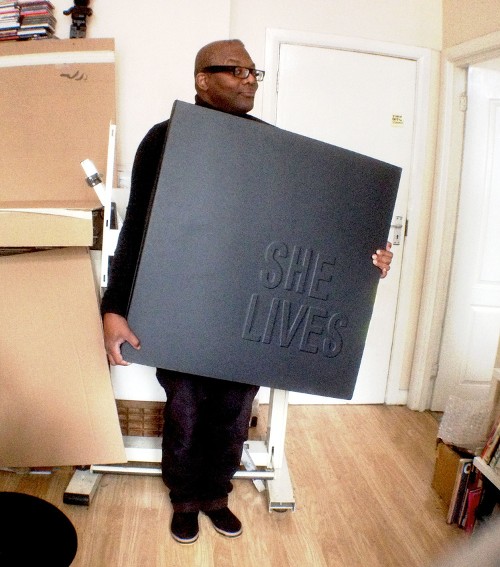

AO: I can’t chat with you without bringing your incredible project She Lives into the discussion. You showed your one-of-a-kind, one-metre tall graphic novel about the Bride of Frankenstein for groups in public readings. It was a fascinating exercise and I want to ask you about your observations of the readers who viewed it. Did you feel their interactions and/or relationship with the page changed given that very different group method of delivery?

PHOENIX: She Lives was initially an investigation into how to control the reading process with giant images. But when it was first displayed I noticed people were reading it together because the lack of text made it possible for them to experience the action as a group instead of the usual solitary activity. So I began showing it that way. It turned the book into a performance because everyone responded to the narrative in real time, as a collective. It made it surprisingly intense! Everyone was concentrating on each page turn and feeling the same things. I did have a conversation with one man who was very exasperated by the lack of control. But even that complaint was a kind of vindication of the experiment because he liked the story so much he didn’t want to be pushed through it. He wanted to hold onto it, take his time and linger on any panels he chose, in a book that belonged to him. I completely understand that feeling. I just had to explain to him this was a different kind of work and that would never happen: the point of this particular piece was that he had to enjoy it there and then.

What readers tell me months or even years after seeing She Lives is the combination of hand drawn artwork, the huge scale and the knowledge that they can only see this once means they really concentrate. The experience stays in their heads afterwards in a much stronger way than if they were able to just buy a book. So that’s why, despite multiple offers from publishers, I’m never going to print it.

AO: You were recently one of the mentors for SelfMadeHero’s Graphic Anthology Programme designed to champion emerging creators of colour which, in turn, led to the anthology Catalyst. This was a hugely important initiative (and one that also featured two of our Broken Frontier ‘Six to Watch’ creators) but despite an indie scene in the UK that certainly for the most part feels progressive in its outlook the number of creators of colour is disproportionately low. You’ve said yourself that the lack of professional provision and access for non-white comics creators is very real. What for you are some of the more recent constructive developments to change that landscape in comics? How should we build on initiatives like GAP to ensure they make a real difference going forward?

PHOENIX: The biggest publishers would rather throw money at already rich and famous celebrities than take a risk in markets they know nothing about, so change is not going to come through them. But I have been enormously heartened by people like Spike with her Iron Circus Comics using Kickstarter to publish the work she wants to see in the world and generating huge readership with her titles. And here in the UK, I couldn’t be prouder to know Shazleen Khan who is well on her way to doing the same thing with Buuza!!.

Not everyone has the drive or the ability to publish themselves, and they need opportunities to get onto the first rung of the publishing ladder through short stories and self-contained pieces, which is why webcomics and print anthologies like Catalyst are vital. Postal charges are insane and it will get even harder to support these initiatives with the Tories hellbent on taking all our money away through Brexit and mini-budgets so learn to love PDFs and shop local, I guess…

AO: We all know the more negative aspects of the comics scene and the challenges that creators face but given that we’re celebrating 20 years of Broken Frontier in this series of interviews we’re asking everyone a variation of this question. Over the last decade or so what have been some of the key positive developments within comics as a scene/medium/industry that you think are worth celebrating?

PHOENIX: I think given the fact that only a handful of people can support themselves solely from making comics in the UK, we don’t have an industry here. Cottage industry, perhaps, with all the hand-made connotations that implies. The medium, though; that’s as strong here as it is anywhere and the possibilities for new kinds of stories just keep expanding from what I can see. It’s frustrating but also wonderful that I can walk into a comics show now and have absolutely no chance of looking at everything in depth because there’s so much work being produced with effective presentation and great quality production values. It’s something to celebrate that I don’t like or even understand some things because it means the scene is expanding and moving beyond a small pool of people talking to each other. On a commercial level I think the continued existence and expansion of independent children’s comics from weeklies such as The Phoenix (no relation) to Okido, Anorak and Scoop is great news. That’s where the next generation of readers and commissioning editors is coming from!

For more on the work of Woodrow Phoenix visit his site here.

To buy books by Woodrow Phoenix:

Buy Rumble Strip here in the UK

Buy Crash Course here in the US

Interview by Andy Oliver

Top BF logo by Joe Stone