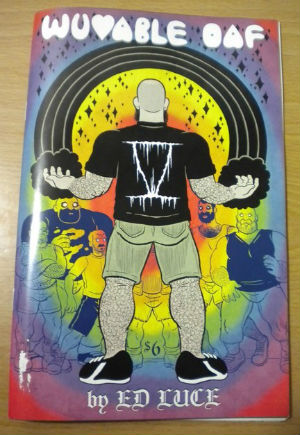

What sustains an artist’s creativity on a series they have been working on for years? When you take a more aesthetic look at the current issue of Ed Luce’s Wuvable Oaf it reveals much of his impetus for the continued focus of this long-running storyline. Wuvable Oaf is a series that holds an important place in indie comics as a uniquely queer male take on the romantic comedy.

Whether they’re gay, straight, or something in between, scores of readers have come to be charmed by the titular Oaf. While Luce’s subversion of tropes once reserved only for heterosexuals as well as his representation of minority groups is highly commendable, much has already been written about this element of his work. Instead let us take a more formalistic approach to Wuvable Oaf V so as to discuss several examples of this extra layer of craft that seems to be propelling Luce forward.

Whether they’re gay, straight, or something in between, scores of readers have come to be charmed by the titular Oaf. While Luce’s subversion of tropes once reserved only for heterosexuals as well as his representation of minority groups is highly commendable, much has already been written about this element of his work. Instead let us take a more formalistic approach to Wuvable Oaf V so as to discuss several examples of this extra layer of craft that seems to be propelling Luce forward.

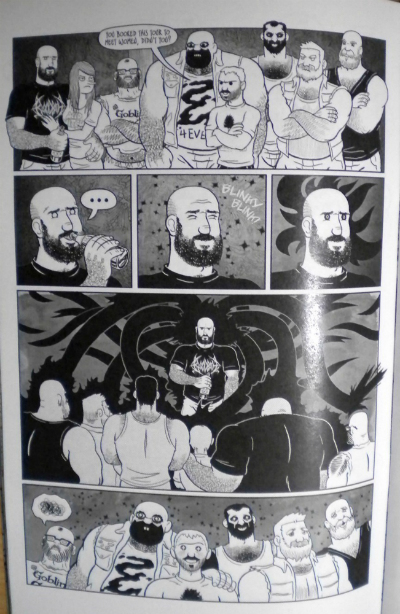

The first half of Wuvable Oaf V continues the plot line of previous issues in the series: that of Oaf trying to solidify his romance with Eiffel, the lead singer of Ejaculoid. This being a romantic comedy, the obstacles in play are Eiffel’s band mates as well as other characters in both their orbits. As this issue will only marginally advance that plot, it is all of the individual set pieces that Luce creates here that highlight his artistic goals. Even from the second page we can start to see Luce using the plot as a means to put images on the page that feel like an end in and of themselves.

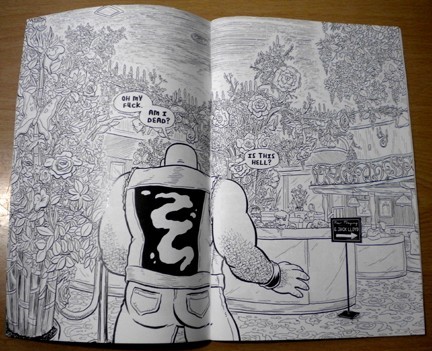

Oaf’s conflicted feelings for all of the members of Ejaculoid could have been rendered in a host of different ways, but Luce chooses to render these emotions as a veiny, phallic hydra threatening to crush Eiffel in a dream sequence. Another artist might have done this more subtly but Luce, in going full Legend of the Overfiend, gets to indulge in making art that is of interest to him while remaining within the boundaries of the story he is trying to tell. Similarly, right after this sequence is a two-page spread of Oaf in his tiny car singing along loudly to his favorite songs. As with any time that specific music is used in a comic, Luce’s choices of song tell us not only about his characters but also lets Luce give a shout-out to said songs. However, the work is not only concerned with references. A two-page splash of a flower-filled dining room with each flower rendered is Luce is either challenging himself or showcasing his ornate drawing ability.

A sequence in which Oaf gets pit shamed reads as a chance to make a joke about #violentbros/#violentOLDbros. The choice of having the tour manager’s girlfriend looking like Megg of Simon Hansleman’s Megg, Mogg and Owl is a nice shout-out to a fellow cartoonist. Lastly, tour manager Marx using dark magic on the band is a chance for Luce to play around with the Black Metal imagery present on so many of the character’s t-shirts. It is clear that Luce is letting himself have fun with the story at this point. With no need to push the narrative significantly forward he revels in getting to do anything he wants. Each two to four-page sequence functions as a chance to hit reset on stylistic concerns and an opportunity for him to cut loose and showcase the myriad directions he can bend his artwork and storytelling to form an engaging page.

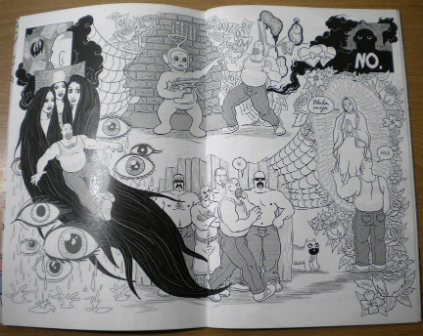

This feels equally true in the flip side of the issue that follows the exploits of the equally oafish, but far less endearing Smusherrrr. Serving as a sort of warped fun house mirror version of Oaf, Smusherrrr is boorish and self-centered, approaching romance with none of the nervousness and earnestness of Oaf. Even his entire identity as a hardened gangsta is a self-aggrandizing put-on. In examining the character of Smusherrrr as well as the character he is playing, Luce gets to render a world that mashes up a variety of pop culture touchstones, such as another two-page splash, this time of Smusherrrr’s psychedelic visions of West Coast Latino culture accentuated by a gun-toting Teletubby.

Smusherrrr’s visit to an “Ex-‐Fake Gangsters Therapy Group” gives Luce the opportunity to put holographic Tupac, background characters from an early issue of Love and Rockets, Marla Singer from Fight Club, and a gangsta-fied Charlie Brown all in the same ridiculous scene. This mixing and matching of styles and influences is neatly echoed in the centerfold pinup pages by Janelle Hessig and Jose Gabriel Angeles. Just as Luce can borrow elements from other cartoonists’ work, so too does he provides equal room for other cartoonists to dip into his.

It is this interplay of style and story telling, this playing fast and loose with established iconography and characters that give Wuvable Oaf V such a burst of life. Even Smusherrrr eventually wins the audience over because while we might not love the character, we can feel the joy Luce has in creating and drawing comedic mishaps for him to get into. While the obvious end point of the series will be the resolution of the Oaf and Eiffel storyline, Luce has allowed for his fictional world to expand in a way that he can put off that event for many years to come, all the while giving him plenty of room to experiment with changes in the story’s focus or changes in formal constraints of the work. This means that even if the conclusion of Wuvable Oaf is far in the future, Luce need not feel shackled to any decisions he made about the shape of the project years ago. No doubt he will have as enjoyable time drawing his way to that conclusion, as the reader will in coming along for the ride.

Ed Luce (W/A) • Self-published, $6.00

You can buy copies of Wuvable Oaf online here.

Review by Robin Enrico