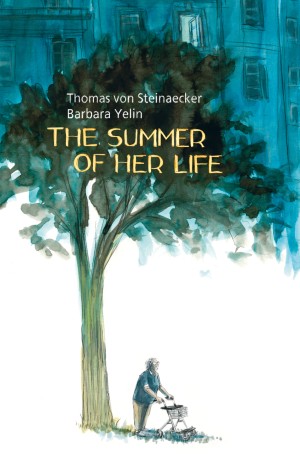

Thomas Von Steinaecker and Barbara Yelin interweave moments from the life of Gerda, an elderly lady in a care home, who dedicates the majority of her present to wandering through the corridors of her past. Steinaecker forces us to confront the painful question of whether our lives have held meaning, and to wonder what it will all amount to in this final stage – when the weight of what has been pushes what is into a pale fog.

Thomas Von Steinaecker and Barbara Yelin interweave moments from the life of Gerda, an elderly lady in a care home, who dedicates the majority of her present to wandering through the corridors of her past. Steinaecker forces us to confront the painful question of whether our lives have held meaning, and to wonder what it will all amount to in this final stage – when the weight of what has been pushes what is into a pale fog.

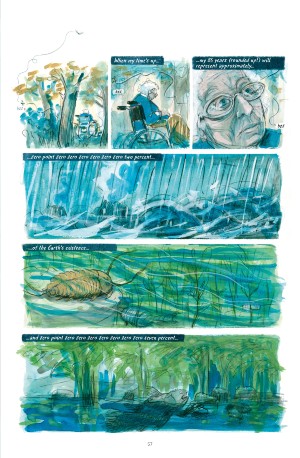

This fog is realised by Barbara Yelin, whose clear and skilful use of colour creates a pervasive binary between the past and present. In the care home, the colours are washed out, giving everything a blue stillness. It is as if we are underwater, with Gerda only managing to break through the waves through the escape of memories and the sunlight of the world outside, which continues turning regardless. The beginning of The Summer of Her Life emphasises this distinction the most; the panels are brimming with brilliant blue tones that Gerda moves through as she makes her way outside. Here, a burst of white and yellow shows the release of the world outside; the world which Gerda’s memories belong to.

This fog is realised by Barbara Yelin, whose clear and skilful use of colour creates a pervasive binary between the past and present. In the care home, the colours are washed out, giving everything a blue stillness. It is as if we are underwater, with Gerda only managing to break through the waves through the escape of memories and the sunlight of the world outside, which continues turning regardless. The beginning of The Summer of Her Life emphasises this distinction the most; the panels are brimming with brilliant blue tones that Gerda moves through as she makes her way outside. Here, a burst of white and yellow shows the release of the world outside; the world which Gerda’s memories belong to.

The blue tones of the care home are a clear contrast to these bright memories, and the fact that the waves first break when Gerda leaves the building and enters the sunlight reinforces the alignment of the outside world with the world that Gerda is no longer a part of. Indeed, in The Summer of Her Life, sunshine and youth are entwined. The days are darkening as the long day is ending, just as the title of the first chapter tells us: “a day is a year is a lifetime”. With this in mind, it is natural that youth is when the sun is highest in the sky, where the panels are brighter, and that the moments in the care home are darker and more subdued.

Steinaecker really brings this notion home through the dialogue between Gerda and another care home patient called Jӧrg. They discuss the excuses their families give them as to why they cannot stay longer or visit as much – they are busy in this world of light and sunshine. In the care home there seems to be nothing left but to be stuck on the outside forever looking in. For a lot of the other patients, this is done by watching TV, but for Gerda this looking is reflected inwards upon herself and her memories. Although watching the TV and replaying memories of the past may be different ways of deflecting from the present, they are still both coping mechanisms for these waning days – providing a release from the acceptance of the end to come.

While others in the care home spend their days watching TV, Gerda spends her time watching the past. She does this attentively and delicately; it is more important to her than the present. It is the realm of childhood exploration, young love, and ambition. The moments captured by Yelin’s illustrations transcend reality and break your heart; they will linger for days after you have finished reading.

Thomas Von Steinaecker (W), Barbara Yelin (A) • SelfMadeHero, £14.99

Review by Rebecca Burke