This article was originally published by Tom Whiteley on his excellent Suggested for Mature Readers blog. We are sharing it here to mark the release of the new hardback edition of Zenith: Phase IV from 2000 AD.

Alan Moore’s influence on Grant Morrison has always been a vexed question. In Supergods, which I haven’t read, he apparently admits that Zenith was pitched halfway between Paradax and Miracleman, between shiny pop culture weird fun and heavy-browed seriousness.

Zenith the character represents the former, fairly obviously; the situations in which he finds himself represent the latter. And Phase IV is Miracleman Book Three reflected in a dark mirror. Narrated from a fait accompli future, it’s the story of the world superhumans make when they’re without human limits or understanding.

Miracleman’s physical superiority was matched by superethics; whatever made him stronger also made him better. His thoughts were poetry, his moral sense was far in advance of ours. The power he held over his world was exercised lovingly, benevolently, with a trust in humans.

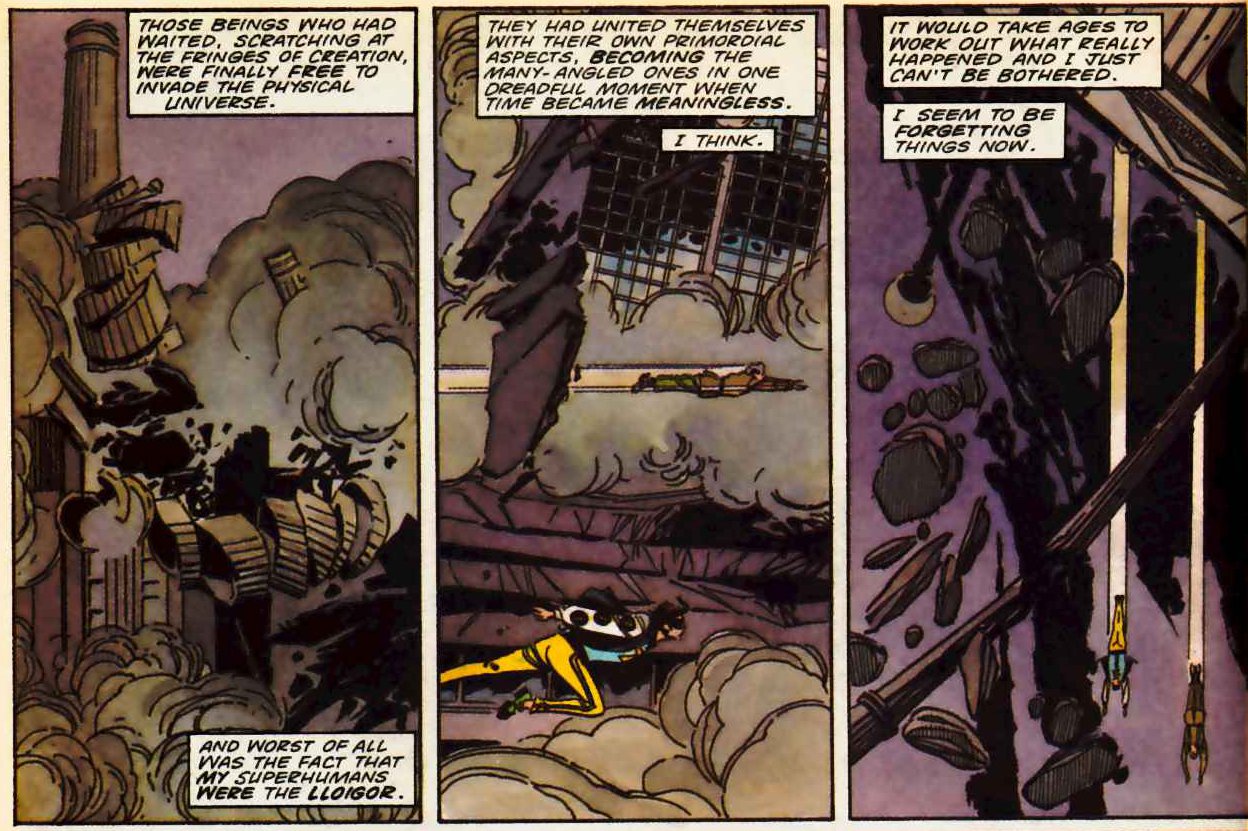

In contrast, Morrison’s government-created superbeings, for whom humanity is just a larval stage, underline that absolute power corrupts absolutely. Indeed, in possibly the first example of a Morrisonian villain standing outside the boundaries of time and space and conventional narrative, they turn out to be the monsters they were fighting all along. They were always intended to replace us.

The dunce’s equation that powers superhero comics, of manifestly superior beings struggling to maintain the status quo for the last rung down on the evolutionary ladder, is exposed as a narrative sham. Do humans dedicate their power to keeping chimpanzee society running smoothly?

Morrison’s writing is known for its weirdness. It’s his USP, his calling card; he had the Doom Patrol fight literary devices and Noel Coward devils, he had Animal Man discover the true nature of his four-colour reality. The Invisibles took the counter-culture of the 1990s and ran it through a psychedelic amplifier. It’s endlessly inventive, and there’s always the feeling that something newer and stranger is round the corner. Like they always say about sci-fi, the ideas are the thing.

But Morrison has many other strengths as a writer, and many other crutches. He’s always loved superheroes, for example, and he’s always loved continuity. Even his Doctor Who shorts reconciled old stories, retconned loose ends. And he’s a big believer in that superhero standby; violence.

While other writers of his generation got the fights over with quickly, or provided a narrative overlay so we were watching more than just punches, Morrison was always happy to go for it blow by blow, panel by panel. I remember reading, as a teenager, the Phase II episode where Zenith fights Warhead and feeling cheated; six pages of fight, very little dialogue. It was antithetical to 2000AD’s supercompressed style and it felt wrong. Of course that’s been an advantage in American comics, where the slugfest is all, and Morrison does choreograph them beautifully.

I’ll get to his other great strength as a writer, characterisation, next time. But Phases I to III of Zenith didn’t have much weirdness. Unsettling edges, certainly, elements that come from outside the traditional heroic narrative and deform it – like all the Old Gods from Lovecraft – but otherwise it’s played fairly straight. There’s none of that complete immersion in another world that had become his trademark across the Atlantic. Zenith’s universe was ours, with the exception of a single ’60s superteam and a pop star.

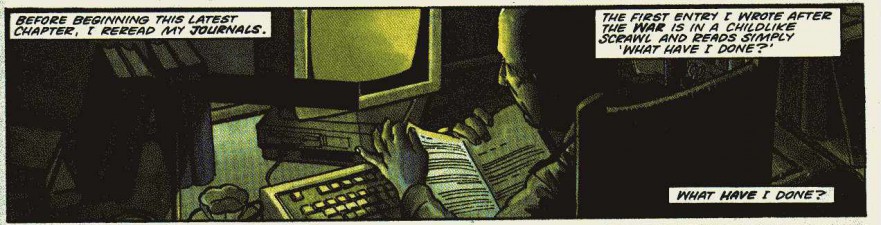

Phase IV changes all that from the first page. For the first time in Zenith we see some narrative rigour, with the framing sequence and narrator lifted from Book Three of Miracleman. There it was the title character in his near-perfected world, a playground for the fantastic, showing it to us while explaining, chronologically, how it came to be. Here we have Peyne, the father of the new age, the last human surviving in the dystopian nightmare his children have created.

Both framing sequences have the same purpose, making massive changes in the world of the narrative inevitable and easier to accept by presenting them as done deals. Zenith had, of course, never consistently used any storytelling devices apart from dialogue and simple chronology, so introducing a narrator is a big step and a sign there’s work to be done, ground to be covered, places to go and things to be.

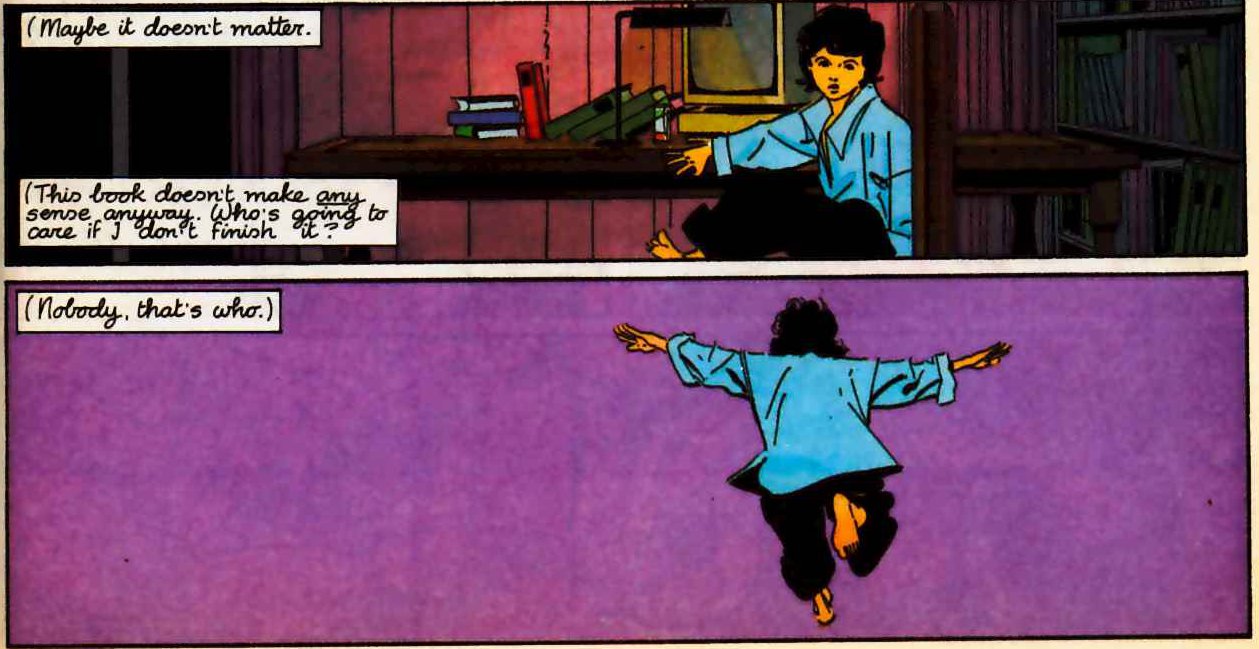

The genius of Peyne’s narration, however, is the twist laid on it. He is getting younger, a dubious gift from his inhuman children, so as he tells the story of his world falling into hell he’s going through the reverse process, from an old man fully cognisant of the doom he’s visited on humanity to a child innocent of his responsibility. It’s an incredibly effective device, giving us a competing narrative set against the main one, one which proceeds by hints and allusions but which arouses the readers’ curiosity far more.

And Peyne’s repeated clues as to the surprise ending get broader, simpler, vaguer as his mind moves backwards through his teenage years into childhood. Miracleman’s narration was almost a problem-solver, a way to cover years of change both quickly and convincingly. Peyne’s narration is at once a way of throwing the main narrative into relief, showing the human cost, and laying a foreshadowing trail through the whole which only becomes properly apparent at the end.

The point of this volume is the unknowability of superhumans to human eyes; Peyne underlines that by becoming more disinterested, more uncomprehending, as the narrative progresses.

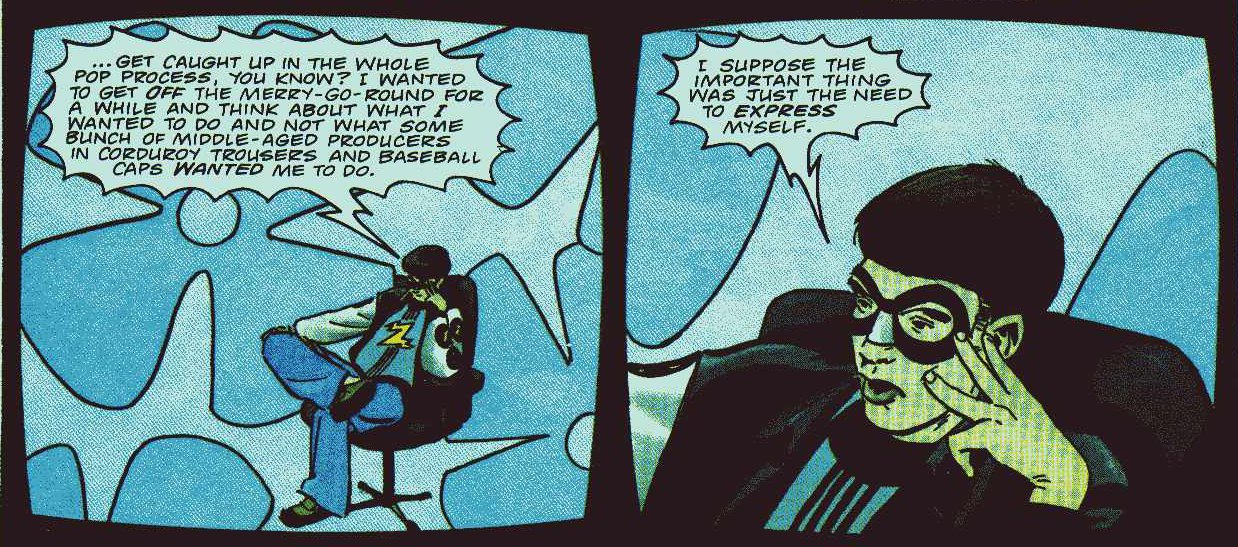

There’s a new look to Zenith, the character and the comic, in Phase IV. The former has gone Madchester, the one-time soul boy jumping on the baggy/rave bandwagon with a bowl haircut and a pair of maracas. He’s rebelled against the artificial pop career he was forced into, dropped the Rick Astley haircut and the shoulder pads, and reconnected with his audience by doing what he wants to do.

Except, of course, that all this is a lie, and like everything else in Zenith’s career it’s been cooked up by his Scottish agent. Insincerity runs deep. The only changes to this supremely superficial character are superficial: new hair, new jacket, the harder edges of ’80s excess replaced by the softer, rounded lines of the self-proclaimed caring ’90s.

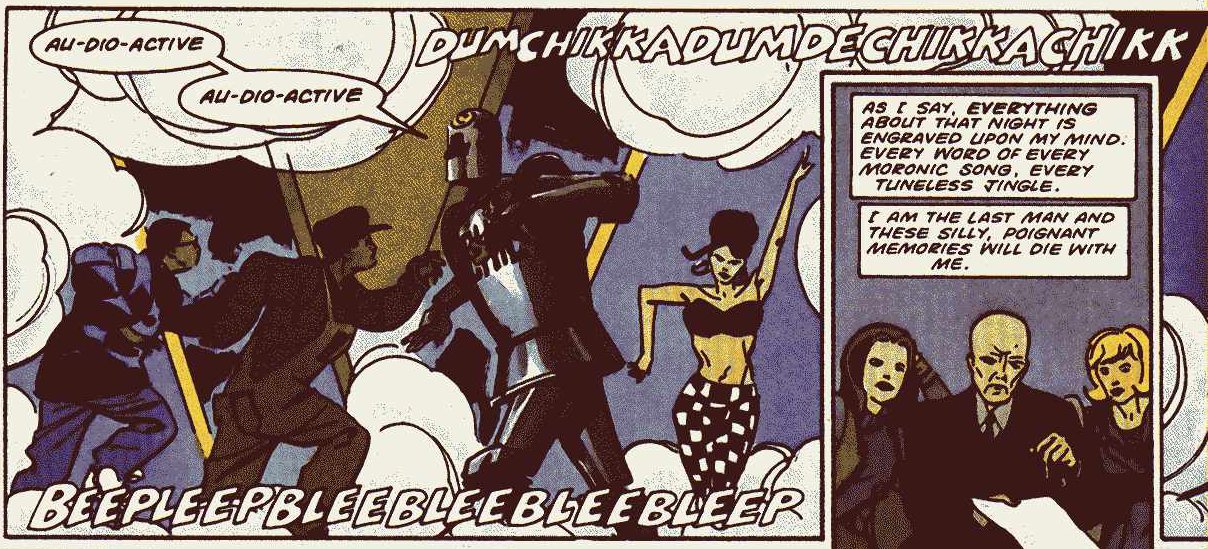

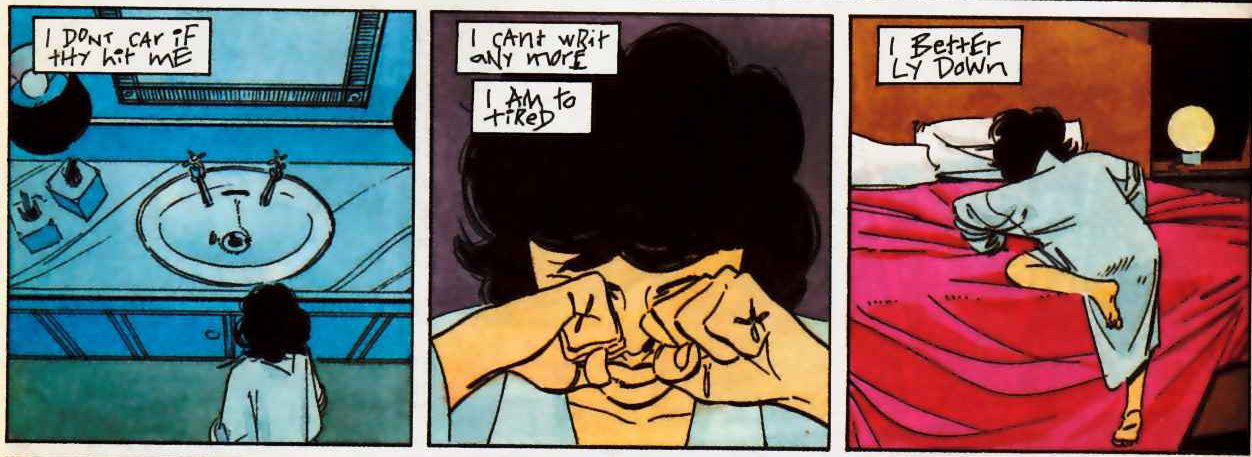

There’s a new look to the art, too: colour. 2000AD had finally gone full colour by this point, so Zenith’s high-contrast black and white was left behind. The change isn’t a welcome one. Yeowell adjusts his art to suit, reducing the blacks and leaving outlines to be filled, and is rewarded with a murky green dystopia like a stick-stirred pond, and a preceding reality of cyan and yellow.

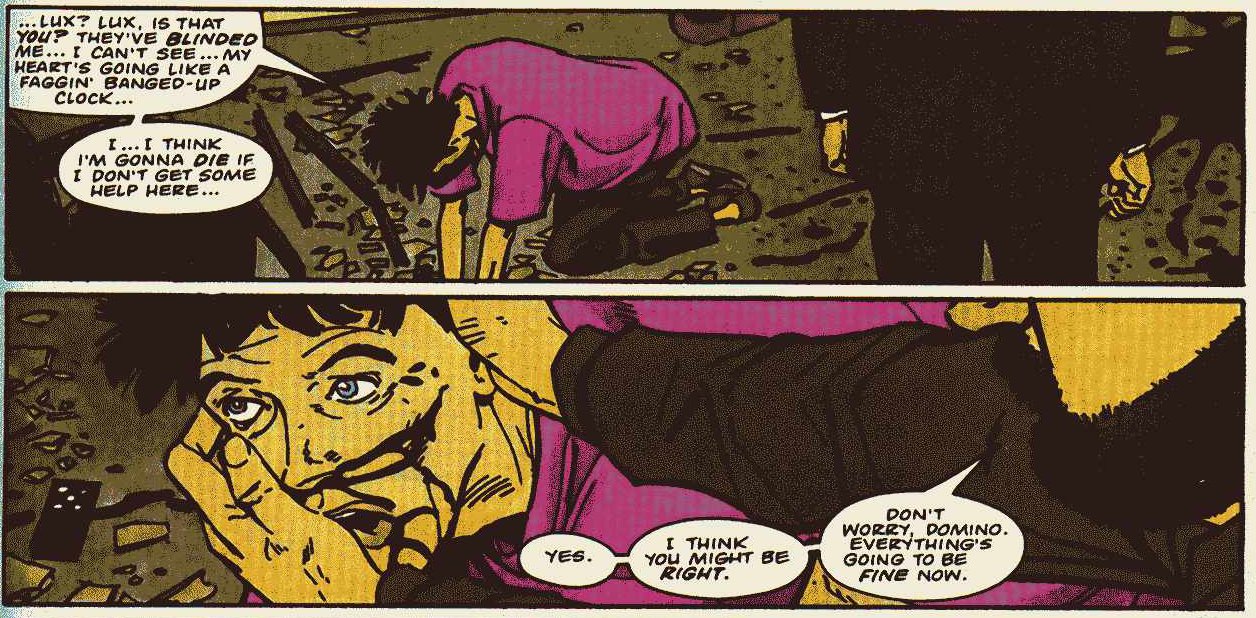

They’re the colours of Zenith’s new man-at-Joe-Bloggs outfit and are extended to be the colours of the whole world: the room where Domino dies, the room where the apocalyptic showdown takes place, even the decor in Downing Street. The palette is garish and, coupled with Yeowell’s sparse backgrounds, makes everywhere into a playroom, which isn’t really suited to the tone of the story. If there’s a good reason for the choice I’d love to hear it. The ruined world, thankfully, subdues the colour a little and allows for an effective conclusion, but I never stopped missing the monochrome.

The status quo we begin with is Zenith reviewing his own appearance on the South Bank Show, fast-forwarding through the dull bits and marvelling at his own mendacity. Eddie the agent – the only consistent human presence in Zenith – takes full credit for hoodwinking the gullible British public in the background.

The remaining members of Cloud 9 have returned to this alternative, as have the survivors of Black Flag, and have launched the Horus Foundation, aimed at helping humanity. (Why they bothered, when they remain committed to the genocidal Plan, is a plot point never explored.) Peter St John has become prime minister after a bloodless takeover from Thatcher, but faces his first election in a few weeks in a close analogue to John Major, his real-world counterpart at the time. (Although physically, St John resembles Thatcher’s eternal challenger Heseltine.)

Black Flag, representing several musical subgenres of the early ’90s given superpowers, remain uncommitted. And loose ends from all the other Phases – the Plan from I, the black sun and Chimera and Shockwave and Blaze and the Zenith breeding programme from II, the evolution of Ruby Fox from III – are picked up and woven into the skein of this final tragedy.

We meet Peyne, chronologically, watching an edition of Top of the Pops featuring Robot Archie in a crashingly accurate parody of the slapped-together dance singles that dominated the chart at the time: a dancer, a sample, a couple of blokes wondering how they got from a warehouse to here. Then Ruby Fox performs, the least likely of them all, a ’60s cover, before Zenith takes the stage and we find out he has an infant son who shares, if nothing else, his dreadful dress sense. There’s something very Grant Morrison about all the superheroes fighting it out in the Top 40, however briefly that’s glimpsed.

With that, and a stilted confrontation between Zenith and St John on one side and David, Penny and Ruby on the other, during which the Chimera pyramid is destroyed, the talking is over. It’s slugfest all the way. The US-ordered assassination of Domino gives him a memorable death scene with practically his only lines of dialogue. In retaliation, Lux and crew destroy the White House and kill the president. St John, Zenith and Archie face off against the former members of Cloud 9 and DJ Chill, who’s joined the bad guys with no fanfare, in a London hotel. Their battle destroys London, perhaps the world.

All of this happens fast. There’s none of the dwelling on atrocity we see in Miracleman or even in Phase III, perhaps because we’d already seen it in those comics. Peyne’s narration glides swiftly over events, acknowledging their haste. Morrison never really defined the powers of his heroes. In a standard superbattle that would be a flaw – one of the things that made The Avengers so successful as an action movie was the clear definition of everyone’s limitations – but it serves this story well.

St John is mental, Ruby’s electric and, for a few wonderful pages, Archie is physical. Everyone else is battling on the astral plane and the robot’s dealing out punches and hitting people with chairs. Even as it delivers the confrontation we’ve been building to for four volumes, this comic can’t resist comedy.

London is ruined. In a second confrontation, Zenith flexes a bit of muscle to create a localised firestorm before St John takes them forward in time in the face of overwhelming opposition. They find themselves in a city under a black sun, their antagonists having discovered they were the Lloigor all along, and face off against them for a third, desperate time.

St John is impaled on the statue of Maximan, just where he and Zenith killed that super-Nazi all that time ago, and Zenith again conjures impressive pyrotechnics before being consumed by the Old God in the body of his own child. The world is remade to a Lovecraftian absurdist hell, surreal and grim and horrifying. All hope, all humanity to understand the concept of hope, is gone. There is only the never-ending scream of Nyarlathotep.

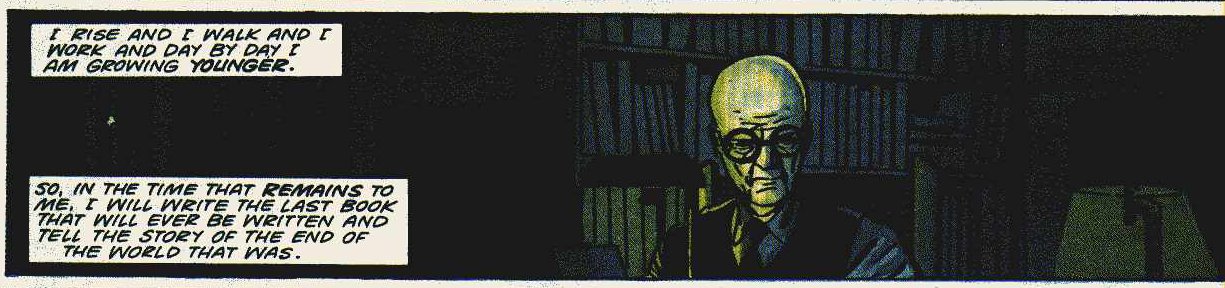

Except. This abbreviated apocalypse is viewed through Peyne’s eyes. And Peyne’s eyes get younger by the day. He narrates St John’s death as a teenager, puzzled about why his favourite superhuman plunged so recklessly into battle. He narrates Zenith’s death as a nine-year-old, at one point abandoning his memoir to go and play in a heartbreaking panel of innocence set against a narrative of unrestrained corruption. He narrates the reshaping of the earth as a child stumbling out of literacy.

And throughout there is an unshakable faith in St John, confused hints of something happening outside of – and unmentioned by – this memoir. Until the final chapter, when Peyne’s narrative voice is restored (rediscovering himself as narrator in a stylistic tic stolen from Peter Milligan) and we discover how St John out-thought everybody all along.

In the epilogue, the terrible Plan having been defeated by good fortune, the mind of a chess player and psychic sleight-of-hand, Zenith, Eddie and Archie are hanging out before a party. On TV, Labour leader John Smith has died of a sudden heart attack shortly before the election, just as he would in the real world two years later. That’s some eerie fucking foreknowledge there, uh?

Zenith goes to his party and walks out, exhausted with his own shallow fecklessness, looking for something new. St John has won the election. The final shot of Zenith is him slumped in the back of a cab, going home, his pop career abandoned. The final panel of the series is St John at his victory party, the Plan defeated but one superhuman’s personal path to power shining ahead of him. There is no suggestion of benevolence, of good, of best intentions. No reason is ever given for St John’s political ambitions. But we do know he has eliminated every possible obstacle in his way.

Darwyn Cooke idiotically failed to find the happy ending in Watchmen. But that and Dark Knight, the dynamic duo of the graphic novel revolution, both end in hope; death the percursor to rebirth.

Zenith, in contrast, ends with the series’ de facto hero as Conservative prime minister – not a position young people of the era placed a great deal of hope in. The real bad guys lost, but there aren’t any good guys around.

Last line of yours really summed it all up. Well done.