To mark the release of the new hardback edition of Zenith: Phase I, Tom Whiteley, the author of the excellent Suggested for Mature Readers blog, has kindly allowed us to post an article on the story that he originally published in August 2012.

Superhero comics beg a question: what if it were me? What if I were the guy with superpowers? What kind of hero would I be?

It’s not a question they answer very often. Most superhero comics, in fact, go out of their way not to answer it. They make the hero some other guy; someone who is definitely not you; someone equipped with universal moral authority or empowered by a bottomless well of tragedy and cash or a test pilot or a police scientist or whatever. DC created sidekicks for their younger readers to identify with, but they’re just fans of the heroes catapulted into the story.

Marvel have Spider-Man, of course, who answers that question full-on. Steve Ditko may have got Stan Lee to write a letter admitting Steve was the creator of Spider-Man, but Lee was the engine behind Peter Parker. His answer: given great power, most of us would use it to show off and make money until the loss of a father figure put us on the path toward good.

But even in Marvel there aren’t many other heroes addressing the question. The Hulk is a monster movie, Thor’s a god, the Fantastic Four are a family, the X-Men are outcasts. Nova was Spider-Man in the 1970s, Firestorm – a personal favourite, I’m never sure why – was Spider-Man at DC. Ultimate Spider-Man asked the same question in a new century.

But otherwise there are relatively few contemplations of what the average comics reader would do if he were suddenly blessed with incredible power. Strange, because the teenage male for whom superhero comics are still written – a boy not at the top of the social tree – spends many an hour fantasising about what he’d do with invisibility or super-strength or flight. Presumably any honest attempt to answer the question would be too hardcore for the audience: decapitated school bullies, empty bank vaults, girls forcibly impressed.

Dan Clowes’s The Death Ray is one of the few works to attempt a realistic answer to the question. What would we do if given super-strength and a ray gun that can remove people from the world?

We’d do the wrong thing; we’d look for opportunities to use them and invent reasons which turned out not really to be good enough. The protagonist ends up more villain than hero when the uses of his powers are tabulated, but is really neither. He’s just a failure, unable to find a great responsibility to live up to his great power. Like Peter Parker or any lottery winner, he discovers that getting what you dream of can really fuck up your life.

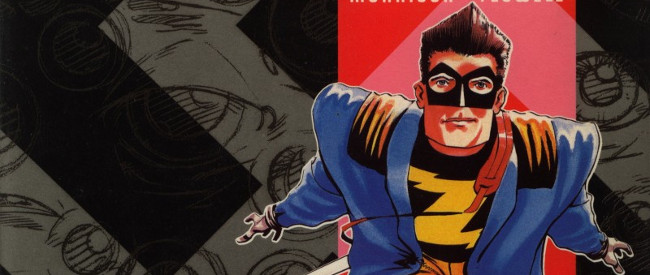

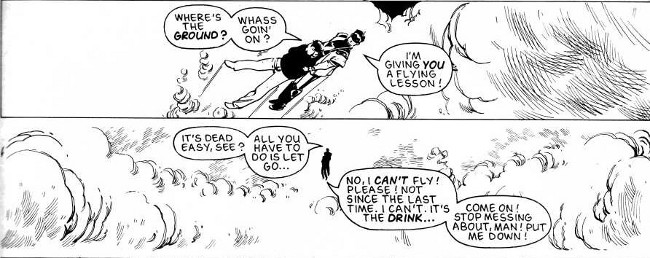

Zenith, the first superhero ever to appear in 2000 AD, is an answer to the question; Spider-Man without an Uncle Ben. Born with powers – flight, super-strength, a bit of telepathy (they’re never properly explored) – he chooses to evade all responsibility. He becomes a pop star instead, a creature of the 1980s in Britain, where being famous gave you a good chance at a musical career regardless of talent.

Zenith, the first superhero ever to appear in 2000 AD, is an answer to the question; Spider-Man without an Uncle Ben. Born with powers – flight, super-strength, a bit of telepathy (they’re never properly explored) – he chooses to evade all responsibility. He becomes a pop star instead, a creature of the 1980s in Britain, where being famous gave you a good chance at a musical career regardless of talent.

I think of him as part of the Stock Aitken Waterman machine, though he’s never identified as such. He’s got the quiff of Rick Astley, the leather jacket of Stefan Dennis, the dissolute partying of Jason Donovan. The music is only there because they didn’t have reality TV back then, singles a fig leaf for fame.

It’s his character that makes this four-phase epic worth reading. Only seen in glimpses in Phase I, Zenith is a vainglorious, self-obsessed, entitled brat whose only actions within screaming distance of heroism are thanks to others putting him in the right place at the right time. He’s a shallow, idiotic party boy who everyone expects to act like a superhero and who never fails to disappoint.

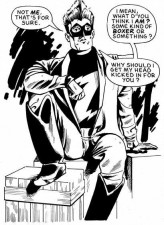

But why should he? His key line in Phase I comes when he’s asked to step up and fight the super-Nazi who threatens the world. On the set of his pop video, in full costume, he replies: “I mean, what d’you think I am? Some kind of boxer or something? Why should I get my head kicked in for you?” Surely he speaks for all of us there. I mean, I’ve encountered bad people who do bad things. I don’t think it’s my responsibility to go and twat them with a crowbar.

But discussion of Zenith’s character can wait. First time out, he’s a sidekick in his own series. Grant Morrison is more interested in establishing his universe, beginning with British hero Maximan in battle with Nazi hero Masterman in 1945 Berlin. And the Brit is getting his arse kicked because his counterpart is a vessel for an Elder God, so it’s good news for everyone when Berlin gets nuked.

The city-sized crater in the heart of Europe is never mentioned again. This isn’t an alternate history that wants to explain itself. Instead, we’re straight into the “present day” and the introduction of Zenith, crashing drunk into his Docklands apartment while simultaneously being interviewed on breakfast TV. Americans won’t know, but the regenerated London Docklands, a flat being called an apartment and breakfast TV (and Zenith’s later reference to rare groove) were all on the cutting edge of modernity in Britain in the late 80s.

So was Morrison’s storytelling. Phase I is a post-Watchmen comic. That crashdown sequence alternates the interview with panels where the interview text alludes to Zenith’s descent – the key storytelling technique of Watchmen. Panels of Masterman holding up Maximan and Zenith are repeated as bookends at the beginning and end. This was a time when the Watchmen techniques were expected to be universally adopted, and when I saw them used I paid more attention on the basis that this guy Morrison, who I’d never heard of before, clearly knew what was going on.

But there’s no attempt at the formalism of Moore; the two chapters with a first-person perspective – one captions and one a diary, both from Ruby Fox rather than the title character – aren’t used to give us that postmodern polyphony. They’re devices to get the action moving along, the latter to underpin a good old training montage.

Otherwise, Morrison writes in a dialogue-led, naturalistic style that owes more to V for Vendetta. He underexplains rather than overexplains, drops names like Cloud 9 but doesn’t trouble to fill the reader in on the details. It manages, like only We3 of Morrison’s subsequent work, to be at once spare and dense; what plays out on the page is simple, clear, but builds a complex picture in the background.

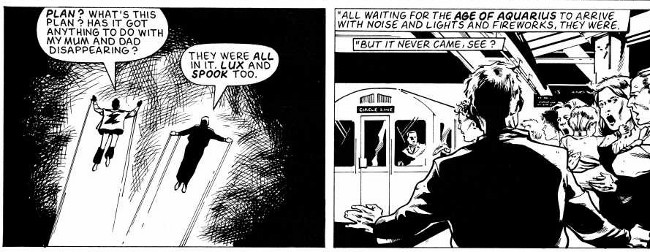

Much of Phase I, however, isn’t much cop. The resurrected Nazi gets a lot of time to be menacing, to build himself up as a threat, but the reader never doubts he’ll be defeated. Elder Gods or not, we’ve read more than 40 years of super-Nazis being trashed by 1987. The three remaining members of British 1960s supergroup Cloud 9 are revealed to still have their superpowers only pages after we’ve learned they supposedly lost them. Their pasts remain opaque.

Much of Phase I, however, isn’t much cop. The resurrected Nazi gets a lot of time to be menacing, to build himself up as a threat, but the reader never doubts he’ll be defeated. Elder Gods or not, we’ve read more than 40 years of super-Nazis being trashed by 1987. The three remaining members of British 1960s supergroup Cloud 9 are revealed to still have their superpowers only pages after we’ve learned they supposedly lost them. Their pasts remain opaque.

Red Dragon comes out of retirement to be killed in the first skirmish – a very revisionist move to undercut the readers’ expectations. I remember being impressed by that, but the years since have diminished its effectiveness; superheroes get killed all the time now. Likewise Zenith punching right through the villain; gore is now the expected standard. And the final victory is a deus ex machina that it’s best to roll right past without thinking about.

Indeed, a lack of thought is necessary to enjoy Phase I. How did Zenith get raised in freedom when he’s a superpowered orphan of Government wards? How does Ruby Fox know everything about the Elder Gods? How did the world’s only three superheroes get away with claiming they lost their powers, especially when one’s an alcoholic?

But the writing style, breezy and contemporary, keeps the eye flowing through a pedestrian plot. Yeowell’s art is perfectly suited to it; never sketchy, with the proportions pleasing, the panels perfectly composed and the solid blacks always anchoring the fine lines, it refuses to let you dwell on it. Years before storytelling became the artists’ thing, back when pin-up shots were the measure of worth, Yeowell emerged with a style that serves the story superbly and hasn’t changed since.

But the writing style, breezy and contemporary, keeps the eye flowing through a pedestrian plot. Yeowell’s art is perfectly suited to it; never sketchy, with the proportions pleasing, the panels perfectly composed and the solid blacks always anchoring the fine lines, it refuses to let you dwell on it. Years before storytelling became the artists’ thing, back when pin-up shots were the measure of worth, Yeowell emerged with a style that serves the story superbly and hasn’t changed since.

The Nazi dies. Red Dragon’s funeral is attended by a couple of mysterious, vanishing figures on a hill and an old bald guy who walks with a stick. Zenith still doesn’t know what happened to his parents, and the unfulfilled Plan of Cloud 9 hovers in the background. Phase I is a short comic and not a great comic, but it’s a very effective promise of better to come.

Grant Morrison (W), Steve Yeowell (A) • 2000 AD/Rebellion, £20, October 2014.